The Scientific Discovery of the Koala: Hat Hill (Mount Kembla), New South Wales 1803

| History | Illawarra Koala | Tolkien's Koala |

|

| Koala at Mount Keira, Wollongong, August 2016. |

The Scientific Discovery of the Koala: Hat Hill (Mount Kembla), New South Wales 1803

Michael Organ BSc (W'gong) DipArchAdmin (UNSW)

[First published online 9 March 2006. Last updated: 22 June 2023.]

Abstract: This paper proposes that the August 1803 description by Robert Brown and drawing by Ferdinand Bauer of the Australian Koala Phascolarctos cinereus as first brought to Sydney from Hat Hill (Mount Kembla) be designated Type Specimens. A detailed account of the European and scientific discovery of the Koala between 1803-4 is given, along with subsequent taxonomy. An abbreviated account is also found in Ann Moyal and Michael Organ, Koala: A Historical Biography, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, 2008. The paper also discusses the visit of Robert Brown to Hat Hill in 1804.

|

| Ferdinand Bauer, [Koalas, collected at Hat Hill, June-September 1803], watercolour on paper, c.1811, Natural History Museum, London. |

It is one of the most extraordinary occurrences in the whole of the story of natural history that such a most peculiar animal should have received no scientific name for eight years afters its first record and even though it was figured three or four times in the meanwhile. (Iredale and Whitley, 1934)

1. Introduction

Who was responsible for the discovery of the Australian native animal commonly call the Koala or, incorrectly, the Koala Bear? To put it more precisely, who was responsible for the modern, scientific, European (aka Western) discovery of the animal scientifically known by the Latin name Phascolarctos cinereus?

The answer is not who one would think, and neither did it take place when one would suspect. The kangaroo, for example, was scientifically discovered in 1770 in association with the expedition of HMB Endeavour under the comman of the English Lieutenant James Cook. And the koala? Well, no. That is a different, rather mysterious, and long drawn out story. "Discovery" is also perhaps an inappropriate term here, for fossil evidence indicates the presence of the koala species in Australia since the Miocene, with fossils dating back 25 million years known from the Riversleigh site in Queensland (Archer et al., 1991).

The local Aboriginal people were obviously aware of the animal's existence from the time of their arrival on the continent at least 130,000 years ago, according to the latest archaeological data, and likely even earlier by other yet unidentified hominid species such as Neanderthals or Denisovans. The Aborigines are known to have made use of the animal for food, skinned it, carved images of it in rocks, and featured it within their art and storytelling (Phillips, 1990). For example, the koala is at the centre of a well-known Aboriginal Dreamtime story from the Illawarra region describing the arrival of the Thurrawal people in Australia (Organ, 1991). It must therefore be said that the Aborigines were the first to name, figure and describe the koala, but not in the Western, scientific sense, such as in writing. However, they knew it intimately and spoke of it in distinct terms. Beyond this, revealing details of the European discovery is not so straightforward a task as one would expect for such an iconic mammal.

W.G. McKay's detailed taxonomic description of 1988 - the modern standard - is unable, for example, to identify the type specimen of Phascolarctos cinereus and makes no reference to those animals first found in Australia. This is not typical. It also points to the fact that no public commentary on this significant gap in the scientific record has taken place up to this point in time.

|

| Aboriginal rock carving of a koala, chalked in to reveal outline, Australia. |

|

| Aboriginal rock carving of a koala, Australia. |

The fact is, the European and scientific discovery of the koala took place between June-September 1803 and involved type specimens collected at ‘Hat Hill’ (Mount Kembla) in the Illawarra district of New South Wales, located on the Australian east coast approximately 50 miles, or 80 kilometres, south of Sydney. Most notably, those first animals brought in to Sydney during August 1803 were immediately figured by the Austrian botanical draughtsman Ferdinand Bauer (1760-1826) and scientifically described, in Latin, by noted English botanist Robert Brown (1773-1858). Both were at the time members of the HMS Investigator survey and scientific expedition under Captain Matthew Flinders (Austin, 1964). Their drawings, descriptions and preserved portions of deceased animal, or animals, were dispatched to England shortly thereafter, during 1803-5.

Circumstances were such that, unfortunately, this information was largely put aside and not worked upon, or published, by the English scientific establishment. Indeed, this local "discovery" of the koala is shrouded in mystery, arising out of the fact that New South Wales at the time was a penal colony, where free and open scientific investigation was not easily accommodated or, indeed, encouraged. In addition, the imprisonment of Captain Flinders at Mauritius between 1803-10 impacted upon plans to publish a detailed account of the scientific and other findings of the Investigator expedition.

The opportunity offered by having on hand in the Colony both an extremely competent scientist and highly skilled artist at the moment of the koala's scientific discovery and description was therefore let slip. Instead, it was taken up a decade later, between 1814-17, by a group of German and French zoologists who, as far as is known, never actually saw a living koala or had access to the June-September 1803 type specimens. The role of Brown and Bauer - "two men of such assiduity and abilities", as Matthew Flinders praised them in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks on 20 May 1803 - in the initial description of the animal was consigned to the level of an historical footnote, where it remains to this day. Why? Well that is a story all by itself.

--------------------

2. Unseen, undescribed, unknown

Captain James Cook and Joseph Banks (1743-1820) had failed to observe and record the koala during their voyage along the east coast of Australia, or landings at Botany Bay and the Endeavour River, in 1770 as part of the HMB Endeavour scientific and discovery expedition. This was understandable, given the fact that the animal mostly resides in the upper storey of trees during the day, where it is disguised therein, and usually only comes down to the ground in the evenings to forage. Whilst Cook missed out on the European discovery of this unique mammal, during his sail up the coast he did observe on 25 April 1770 “...a round hill the top of which look’d like the Crown of a hatt,” in the vicinity of modern-day Wollongong (McDonald, 1966).

|

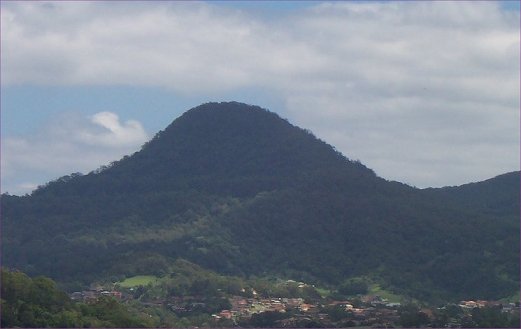

| Hat Hill (Mount Kembla), Illawarra, New South Wales, Australia. |

This feature, which was labelled Hat Hill on the earliest maps of the Colony and known as such by the first European settlers and explorers, was later given its Aboriginal name Kembla and figured in the subsequent scientific discovery of the koala. The modern Mount Kembla is quite distinctive, located as it is adjacent to the Illawarra Escarpment near Wollongong. Flinders noted it during his visit to the region and nearby Lake Illawarra in 1797 and included reference to it in his map of the Colony prepared at the time. At the time Flinders also noted the presence of escaped convicts residing in the area and thier growing of potatoes, just on a decade after the arrival of the First Fleet. It was not until some 5 years later – August 1803 - that a koala was brought in to Sydney from the Mount Kembla area for detailed scientific description. Obviously this delay was due to a variety of reasons, including the likelihood that none of the animals were living within the close confines of Sydney Harbour or the immediately adjacent forests. Furthermore, communications with the Aboriginal people were not such as to facilitate a free supply of information about the animal to those few amateur natural historians working in the Colony amongst the military and convicts during its first decade. These included the soldiers Lt. Dawes and Captain Hunter, and a variety of convict artists. Also, extant written records are scant, reflecting the penal nature of the somewhat notorious settlement then known as Botany Bay.

The koala's eventual arrival at Port Jackson in August 1803 was immediately reported in the Sydney Gazette, followed by an intense period of investigation, discussion and recording by then resident scientists and natural history artists. Robert Brown and Ferdinsnd Bauer were involved, as described above, alongside local natural history painter John Lewin (1770-1819), whose drawing of the animal was the first to reach England in 1803. Also participating in the story of the animal's scientific discovery were botanist George Caley, amateur scientist and Lt. Governor Colonel William Paterson, and colonial Governor Philip Gidley King.

During this initial flurry of activity more specimens of the rather sedate animal were obtained and some sent to England, usually preserved in a jar of alcohol or as skins. However, it was not until some seven years later, in 1810, that the first image of the koala was published in England within George Perry's Arcania, and a further seven years - 1817 - before it was finally allocated the scientific name Phascolarctos cinereus, by which it is known today. This is unlike the kangaroo, which had been first illustrated in accounts of Cook's voyage to Australia.

The relatively slow process of publically describing and naming the koala was initially outlined in Iredale and Whitely (1934). Though that paper is an important and still useful reference, elements of the story were unknown to those authors at the time of its writing. As a result, the learned Australian scientists made a number of statements which cannot now be verified, or have subsequently proven to be erroneous. One important missing piece to the puzzle was the existence of detailed drawings in pencil and watercolour of specimens taken by Ferdinand Bauer in Sydney, with the earliest dated 15 August 1803 and which this author herein refers to as Type. The watercolours remain some of the most exquisitely beautiful and scientifically accurate depictions of the koala ever produced. Another element unknown to Iredale and Whiteley is the link to Hat Hill, Illawarra, where the animals were originally captured. A third concerns documents outlining the role Lt. Colonel William Paterson played in their capture and subsequent dispatch to England for further study. A fourth unknown element, equally as important as Bauer's sketches, existed in the form of the detailed manuscript notes, in Latin, by Robert Brown, describing the animal, originally taken whilst in Sydney and subsequently worked upon in England, though never published by him.

We should therefore ask – what were the precise details of the modern, scientific discovery and description of the Koala? It is only in recent years that we have been able to attempt to answer this question with any precision. When the Ferdinand Bauer suite of finished Koala pencil drawings were first exhibited in Australia during 1997, the accompanying catalogue noted in passing that they were of a specimen "Shot at 'Hat Hill', New South Wales, June-September 1803" (Watts et al., 1997). This reference was extracted from Robert Brown's copious manuscript notes in the Museum of Natural History, London. The 18 page manuscript in latin had been unearthed by Alwyne Wheeler and D.T. Moore and reported during 1994, revealing a detailed description of the animal. Unfortunately Brown's work rested alone in the colony at that time, without further context, for no records are known of any official or unofficial expeditions to Hat Hill or the Illawarra during 1803 to collect flora and fauna or further specimens of the Koala, though they did appear shortly thereafter in Sydney, dead and alive. It has been variously recorded that the following year, in 1804, Brown collected type specimens of the Australian native birds the Spine-tailed Log-runner and Purple-breasted Pigeon at Hat Hill, and that he was accompanied there by local ex-convict guide Joseph Wild ([Brown] 1827, Gibson, 1958). Once again, no corroborative evidence has been found for such a visit. We therefore have indications of identified and unidentified bird and animal collectors at Hat Hill in 1803 and 1804, but no detailed accounts. Who were these visitors? Robert Brown? The ex-convict, or possible Aborigine Joseph Wild? Were a group comprising local Aborigines, explorers such as Ensign Francis Barrallier and George Caley, unknown free settlers, escaped convicts, or soldiers ordered there on duty? Such questions have cast doubt on the veracity of a visit to the Illawarra at any point in time by Robert Brown (Robinson, 1980). Furthermore, Robert Brown expert and Bulli horticulturalist Ray Brown suggests that the Hat Hill bird specimens were collected by unknown bird collectors (Brown, 2003). So what is the truth? Did Robert Brown journey south of Sydney to the Illawarra rainforest in search of heretofore undescribed plants and animals in 1804, as suggested? Who collected the type Koala specimens at Hat Hill in 1803? What were the circumstances of the discovery and description of these animals? And what of their fate? In order to answer these questions we need to go back to the primary source documents - to the manuscript and published records of the time, both the written and the pictorial, and look anew, or for the first time in this context.

--------------------

3. The Discovery of the Koala - Hat Hill, June-September 1803

The scientific and European discovery and delineation of the Koala was a relatively long, drawn-out process. Thought to have been a sloth or monkey when first sighted in the bush outside Sydney between 1798-1802, it was not until 1816 that the Koala's physiological identity and heritage was publically revealed and scientifically described and figured. There are many reasons for this delay, least of all the sedentary and somewhat secretive nature of the animal itself, Sir Joseph Banks' interest in promoting the flora of Australia ahead of the fauna, and Robert Brown’s similar preference. Though it must be said that this was during a period when the publication of illustrated scientific tomes was an expensive and difficult process, the number of scientific societies in England was small, providing limited outlets for article publication, and the task of scientific discovery in regard to Australia was a largely exported, external endeavour, and not the singular purview of the British. There was also a reticence on the part of local authorities to allow individuals - be they soldiers, free settlers or convicts - to explore beyond the confines of the penal settlement at Port Jackson, and this carried through to the second decade of the nineteenth century. The stalling of the Investigator expedition publication program due to the imprisonment of Matthew Flinders at Mauritius was also a factor. As late as 1836 the Koala was still being referred to by the term "monkey" in the Colony, and "Native Bear" likewise remained in use throughout the nineteenth century. Initial descriptions of the animal were not favourable - it was considered sloth-like, lethargic and ugly, and did not compare well in comparison with more exotic and supposedly interesting species such as the Platypus and Kangaroo.

The first reference to the Koala – therein recorded as a “cullawine” from the English hearing and adaptation of the original Aboriginal word - did not come in 1788 from a First Fleeter, but a decade later in an account by 19 year old John Price. During January 1798, whilst on a journey through the Bargo / Mittagong region located approximately 60 miles south-west of Sydney, Price recorded the following entry in his diary:

There is another animal which the natives call a cullawine, which much resembles the sloths in America. (Price, 1798 [1895])

This brief comment would suggest that Price actually saw a Koala, perhaps resting in the branches of a tree like a sloth, or a dead specimen collected by Aboriginal guides in order to be eaten. Price’s journal was not published until almost a century later, in the official Historical Records of New South Wales (HRNSW) series issued by government during 1895. His sighting was not made public at the time, and the Koala remained unknown until further information was obtained by Ensign Barrallier four years later. With the local authorities distracted by Irish rebels (1798), ongoing friction between government and the New South Wales Corp, and the eventual Castle Hill rebellion (1804), the pursuit of scientific discovery was not a high priority within the colony during this period. Nevertheless, early in November 1802 Ensign Francis Barrallier (1773-1853) was engaged by Governor King to lead an exploring expedition south west of Sydney towards the Blue Mountains and Nattai, in the forested region about the Nepean River, behind the Illawarra Escarpment and to the west of Cook's aforementioned Hat Hill.

Barrallier, a talented surveyor and engineer who arrived in Australia in April 1800, had undertaken a number of semi-official exploring expeditions prior to receiving King's commission. For the November - December 1802 excursion Barrallier was well supplied with provisions and transport, and accompanied by a party which included the Aboriginal guide Gogy (Smith, 1984). They were also later joined by local men Bulgin and Bungin. On 8 November the Aboriginal leader Canambaigle and his tribe - later massacred in 1816 at Appin on the orders of Governor Lachlan Macquarie - carried out a hunt for food by setting fires in the area of Barrallier’s depot. Bulgin and Bungin joined in and were given body parts (no head) of a Koala to eat in return for their assisting in the hunt. The next day they returned to camp and Barrallier noted the strange animal which was about to be consumed by his guides. He was able to bargain for the strange, 5-toed feet of the "monkey" or “colo” (Koala) from the Aborigines and send them off to Governor King in a bottle of spirits. Barrallier’s account of the discovery, originally written in French and dispatched immediately to Banks, did not appear in print until much later, in 1897, like the Price diary entry. The relevant section reads as follows:

Gogy told me they [Bulgin and Bungin] had brought portions of a monkey (in the native language “cola”), but they had cut it in pieces, and the head, which I should have liked to secure, had disappeared. I could only get two feet through an exchange which Gogy made for two spears and one tomahawk. I sent these two feet to the Governor in a bottle of spirits. Gogy told me that this portion of the colo (or monkey) and several opposums had been their share in the chase with Canambaigle…… (HRNSW, 5, 759)

Iredale and Whitely (1934), in their account of the discovery of the Koala, state that Barrallier later gave a live specimen to Governor King for transport to England and that it did not live for long. However, the reference for this is not given, and it is likely a conflation of the above account regarding the presentation of oreserved feet. It is also a statement is in conflict with the later reports of the first animals reaching Sydney around August 1803, not via Barrallier in December 1802. Barrallier was actually in England by August, having left the Colony during May 1803. Therefore any collection of a specimen by him would need to have taken place in the months between his return to Sydney on 24 December 1802 and subsequent departure. No such record exists. It appears that Iredale and Whitely were confusing Barrallier's activities with some of those later carried out by Lt. Governor Colonel William Paterson, commander of the New South Wales Corps. Such a confusion is understandable.

The exploring expeditions of Ensign Barrallier, whilst actively supported by Governor King, were never officially sanctioned by the military authorities back in England. In July 1802 Colonel Paterson received an order from his commander-in-chief, the Duke of York, that soldiers of all rank in the Colony were not to engage in farming or non-military activities such as scientific expeditions (HRNSW, 2, 992). Paterson informed the Governor of this in October, by which times preparations for Barrallier's expedition were in train. King was therefore required to use subterfuge to ensure the continuing services of the knowledgeable Ensign in such activities concerning both geographical and scientific discovery. He therefore took him on as aide-de-camp and proceeded with the November expedition to the Nepean River. Barrallier's work was, as a result, subsequently shrouded in a degree of secrecy. We therefore do not know the precise details of his journeyings, if any, during the first part of 1803, or whether he visited the Illawarra region in possible search of the Koala. Barrallier does note in his journal at the end of December 1802 an intention to travel to Jervis Bay, located on the coast south of Hat Hill, and return to Sydney from there, but no record survives of such an expedition taking place. It would therefore seem that Iredale and Whitely’s uncited reference to Barrallier providing a live Koala specimen to the Governor cannot be substantiated. If Barrallier did provide an animal to King, then the latter would have to have kept it secret until August. This is highly improbable, and as no evidence exists that such was the case we should therefore dismiss the idea of Barrallier playing a part in the August 1803 discovery, apart from his tweaking local interest in this unknown animal by the provision of the two preserved paws at the end of 1802, knowledge of the receipt of which in Sydney would quickly have spread amongst senior members of the colonial administration and those interested in scientific endeavour and discovery.

It is unclear what happened next, and what level of interest the paws raised upon arrival at Government House. Was an expedition mounted specifically to search for the animal, or would exploration and identification of land suitable for settlement continue to be the priority? Was the Aboriginal guide Gogy asked to secure an appropriate specimen and bring it in to the authorities? This is possible. Or was the animal accidentally encountered by settlers, convicts or soldiers engaged in hunting expeditions in the region of Hat Hill? Whatever the truth, indications are that as early as June 1803 collectors were present in the Hat Hill area on the coast south of Sydney, and it was here that the first, live Koala was secured for dispatch to Sydney and initial scientific study.

--------------------

4. The Brown and Bauer description and drawing August 1803

The earliest detailed record we have of a Koala is Ferdinand Bauer's pencil sketch dated 15 August 1805 and at present part of the Bauer collection housed in the Natural History Museum, Vienna (Riedl-Dorn, 2001). It is inscribed therein:

Koalas, Phascolarctus cinereus .... from the South of Port Jackson, August 15, 1803.

This important image records the first animals seen in Sydney and subject to detailed study by Brown and Bauer. Whilst the second half of the inscription indicates when the drawing was originally taken (i.e. 15 August 1803), the first half of the annotation (i.e reference to the Latin name Phascolarctus cinereus) dates it to 1821 when this name was first applied in the scientific literature through Waterhouse's Natural History of Mammals (1821). Likewise, the surviving manuscript description by Robert Brown, based on original notes taken in August 1803, is on paper watermarked 1814 and includes a note at the top listing Phascolarctus cinereus from 1821. An English translation was published Koala: A Historical Biography (Moyal & Organ 2008):

In sylvis ad radices montium prope Hat Hill Potitans foliis Eucalypti...

Natural habitat: In the forests at the foothills of mountains near Hat Hill continuously feeding on the leaves of the Eucalyptus.

Name according to the Native dweller (Native name), 'Coulo - Kola - Koulou' as an animal which is constantly chewing.

Length from nose to tail two feet one inch.

Largish head about 5 inches long. Between the ears 4 inches long with a slightly obtuse blunt beak, with a slightly convex / rounded forehead.

Blunt nose divided into two halves through the middle; blackish; somewhat truncate, i.e. ending as if cut straight across; slightly convex / rounded, covered with dark skin sparsely covered with a few short hairs, 13-14 lines wide, hairless through the length of 15 lines. Spatulate nostrils, i.e. from a broad upper part tapering gradually downwards; with the inner lower angle slightly acute. Upper lip divided into two parts, lower a little prominent. A few short black chin hairs.

Small eyes not slightly prominent With a greyish iris With a black pupil shaped like a lance (broad in the middle and tapering to a point) going downwards. Dark eyelids. Eyebrow with a few black spreading hairs. Large flat spatulate ears, rounded somewhat truncate, i.e. ending very abruptly as if cut across, on both sides shaggy with fairly long straight hairs with the inner hairs white 3 inches long.

Tongue not remarkable.

Teeth six upper front incisors of which the two intermediate larger teeth three inches long with the tip truncated very simple coming into contact at the base on the other side standing apart in a line with the tips touching at an acute angle with the diameter of the convex tip point one and a half lines on the outside with the sides angled in relationship to the tooth nearer to it, with the outer teeth and the ones in between of medium size approximately shorter to the extent of one line - long, truncate, simple. The lower teeth. Two larger teeth with truncated cone-shape directed antroversely i.e. from the base standing apart a little with the tips touching. 4 and a half lines long with the diameter of the tip obliquely cut more than 1 and a half lines. The intermediate teeth. upper only. two standing apart from the first submolars with these - fairly close to two lines long; in a line; with the tip significantly more enlarged; shallowly notched.

Feet five toes with two thumbs[?] with the inner separated from the rest 5 toes fingers 4 are clawed Palms bare with dark skin . Male larger with larger head with smaller ears and eyes.

Penis with foreskin without a frenum i.e. the ligament which attaches to the inside of the foreskin of the glands. With the left gland oblong, with spines, acuminated i.e. tapered with stiff scales / spikes turned backwards with a short ... [indecipherable] approximately two-thirds of a line long with the tip slightly scabrous i.e. rough to the touch, with the tip divided into two parts with semi-bilobule tears [semen]. Urethra ended in penis. The seminal vessels soft. The Vasa Deferentia, small glands, wrapping around the tip of the Prostate at the back.

During August-September 1803 Bauer was to make a number of sketches which would later be turned into detailed watercolour drawings, most likely in preparation for publication.

A week after the aforementioned 15 August drawing was made, on 21 August 1803 the Sydney Gazette informed the public that the first specimens - an adult and two young - of a new species similar to the ground dwelling and burrowing Wombat had arrived at Port Jackson. It read as follows:

An animal whose species was never before found in the Colony, is in His Excellency’s possession. When taken it had two pups, one of which died a few days hence. This creature is somewhat larger than the Waumbut, and although it might at first appearance be thought much to resemble it, nevertheless differs from that animal. The fore and hind legs are about of an equal length, having five sharp talons at each of the extremities, with which it must have climbed the highest trees with much facility. The fur that covers it is soft and fine, and of a mixed grey colour; the ears are short and open; the graveness of the visage, which differs little in colour from the back, would seem to indicate a more than ordinary portion of animal sagacity; and the teeth resemble those of a rabbit. The surviving pup generally clings to the back of the mother, or is caressed with a serenity that appears peculiarly characteristic; it has a false belly like the apposin, and its food consists solely of gum leaves, in the choice of which it is excessively nice.

Who brought these animals to the Governor – unknown

collectors? Local Aborigines? Members of the military? In order to answer these questions we need to look at any additional

contemporary records. The first is a letter written during September 1803 by

Robert Brown to Sir Joseph Banks, in which he can be said to identify the Koala

as Didelphis coola, or Didelphis cooloo, a species of Wombat. The letter

states, in part:

A new and remarkable species of Didelphis has been lately brought in from the southward of Botany Bay. It is called by the natives cooloo or coola, and most nearly approaches to the wombat, from which it differs in the number of its teeth and in several other circumstances. The Governor, I learn, sends a drawing made by Mr. Lewin. Mr. Bauer cannot on so short a notice finish the more accurate one he has taken. The necessity of sending my description, which is very imperfect, as the animal will not submit to be closely inspected, and I have had no opportunity of dissecting one, is in a great measure superseded by Mr. Truman having purchas’d a pair, which from their present healthy appearance, will probably reach England alive, or if not, will be preserv’d for anatomical examination. (HRNSW, 5, 228)

Brown's letter points to his early identification and naming of the Koala as Didelphis coolaa / coola. Unfortunately, this was never made public, or published, by him, and he never made claim to the scientific discovery of the animal, though the records prove, or suggest, otherwise. The letter also highlights the fact that Bauer worked slowly in the production of his highly detailed images of plants and animals. First he would produce a detailed pencil sketch, and then it would be annotated with numbers indicative of colour (Norst, 1989). These would assist him later in the preparation of finished, coloured drawings. Brown's comments further suggest that Bauer was in the process of completing a finished drawing, as opposed to mere pencil sketches. Of course they were not ready in time to be despatched to England with various letters in September 1803, though a drawing by local artist John Lewin was.

Governor King also wrote to Banks around the same time – September 1803 - commenting:

Another animal has been added to the natural history of this country. As you will have an account of it from Mr. Brown and Mr. Bauer, I shall not attempt its description. The first that was brought in was a female. Since then more has come in and some of the males. I much fear that their living on leaves alone will make it difficult to send them to England. (HRNSW, 5, 229)

A second, short notice of the Koala appeared in the Sydney Gazette six weeks after the initial report, on 9 October, indicating additional live specimens had been obtained:

Sarjeant Packer of Pitt's Row, has in his possession a native animal some time since described in our paper, and called by the natives, a Koolah. It has two young, has been caught more than a month, and feeds chiefly on gum leaves, but also eats bread soaked in milk or water.

--------------------

5. The Artworks

In regards to art works, we know that two additional depictions of the Koala by Lewin were made and sold to Governor William Bligh, who noted such in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks dated 7 February 1807 (Neville, 1997). Three watercolours by Lewin of the Koala are therefore known. The earliest presents a view of the mother and child as also seen in the Bauer drawing. Signed and dated 'J.W. Lewin N.S.W. 1803', it was acquired from a descendent of Governor King and is in the collection of the Mitchell Library, Sydney.

|

| John Lewin, [Koala and young], watercolour on paper, 1803, Mitchell Library ML896, Sydney. |

Another work, dated 8 July 1804, is in the Thomas Hardwicke Collection, Zoological Library, Natural History Museum, London. The third, also depicting a mother and child, plus a male on a branch, survives in the collection of the British Library. It is annotated:

Coola, an animal of the oppossum tribe from New South Wales. (British Library, NHD 33/40).

It is illustrated below.

|

| John Lewin, 'Coola, an animal of the oppossum tribe from New South Wales', watercolour on paper, [1803], British Library. |

It is possible that the first of these watercolours was the drawing sent to Banks in England in September 1803, upon the initial point of scientific discovery of the animal. It was subsequently turned into a print for use within the various English editions of Baron George Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom, first published in 1827. The plate is therein noted as having been engraved during 1824 and the animal stated as inhabiting the banks of the Nepean River area of New South Wales, though the source of this reference is not known. This image was subsequently reproduced in a variety of European works, such as the Okens Allgemeine Naturgeschicht fuer alle Staende, published in Germany in 1843.

|

| Koala, engraving (section), Okens allgemeine Naturgeschicht fuer alle Staende, Stuttgart, 1843. |

Both the Brown and King letters of September 1803 referred to above were most probably written in haste and dispatched to Banks early that month by the first available ship. This was obviously before Brown had time to deal with the Koala specimens in any great detail, though other records suggest he very quickly had access to a deceased animal and was able to dissect it. The letters also indicate that Brown and Bauer were working on detailed delineations of the animal, most likely for publication in the planned account of the Investigator expedition. We know that Ferdinand Bauer drew the Koala shortly after its arrival in Sydney, and five finished watercolour drawings by him of these animals survive in the collection of the London Natural History Museum (Norst, 1989; Wheeler & Moore, 1994; Watts et al., 1997). They date from around 1811 and are of a female adult and baby (1-2), two adults on branches (3), a skull and limbs (4), and a study of two heads (5).

Bauer completed his numerous drawings of Australian plants and animals both whilst in the Colony and later back in England between 1805-14, before returning to his home country of Austria. The five finished watercolours of the original Hat Hill Koala specimens may therefore represent a combination of the work the artist did during August 1803 and later. Wheeler and Moore (1994) point out that the head study drawing is on paper watermarked 1811, indicating that the collection may have been prepared around this time. All were obviously based on Bauer's original detailed pencil sketches taken whilst in Sydney, however we should not discount the possibility that some also date back to 1803. We know of one of the original pencil sketches surviving amongst the more than 2000 such items by Bauer in the collection of the Department of Botany at the Natural History Museum, Vienna (Norst, 1989).

Associated unpublished manuscript notes by Brown state that the animals depicted by Bauer were shot at ‘Hat Hill’, New South Wales, between June-September 1803 (Wheeler and Moore, 1994). The relevant section of the notes, in latin and spread over 18 pages, reads in part:

"In sylvis ad radices montium prope Hat Hill Victitans foliis Eucalypti &c..."

[In the forests at the foothills of mountains near Hat Hill continuously feeding on the leaves of the Eucalyptus, etc.]

It is unclear whether Brown, in noting the reference to Hat Hill, was referring to the specific locality or the general area. At various points the notes also make reference to Brown's original 1803 scientific classification of the animal as Didelphis Coola, and to the later Phascolarctos Koala used in 1827. The watermark of the note paper is dated 1814, suggesting that this material was recompiled by Brown from his original work books and diaries, and annotated at various stages thereafter. The notes also make specific reference to Bauer's Koala drawings, which were first illustrated and annotated with reference to Brown's manuscript notes in Watts et al. (1997).

Additional contemporary references to the precise collection locality of the specimens exist in the form of Brown's vague statement in his letter to Banks of September 1803 that they came from "southward of Botany Bay" and Bauer's "south of Port Jackson" annotation. The Bauer Koala drawings, along with Brown's manuscript notes, therefore represent a detailed description of the original type Koala specimens which arrived in Sydney from Hat Hill in August 1803. The failure of this material to be published at the time is unfortunate and lead to confusion and delay in the scientific exposition of an important new species of mammal.

--------------------

6. Caley and Paterson

The other resident botanist and professional natural historian in the Colony at the time of the Koala discovery was George Caley (Else-Mitchell, 1939; Andrews, 1984). Caley did not appear to show much interest in the description of these strange new animals, though he did write to his patron Sir Joseph Banks from Parramatta on 18 September 1803, noting that the Koala had lately been brought in to the Governor and Colonel Paterson:

"... they are called by the natives when they are caught Cola.” (Mitchell Library, SLNSW, CY6803).

Caley's own stuffed specimen eventually found its way to the museum of the Linnean Society in London, following his return to England in 1810 and the sale of his collection in 1818.

An important player in this saga appears to be the amateur naturalist and Lt. Governor William Paterson. According to a letter to Banks dated 10 March 1804, Paterson was responsible for first bringing the Koala to Sydney and also domesticating the animals noted in the Sydney Gazette report of 9 October 1803. The relevant section of his March 1804 letter reads as follows:

“….a bad state of health has hindered me from attending much to natural history. I have however a Capt. in the Regiment who I employ to go in the woods and sometimes he is very successful, particularly in shooting both quadrupeds and birds. It was this man who discovered the Cooler which I gave the Governor, being the first ever seen here. Mr. Lewin made a very bad drawing of it which the Governor informed me he had sent to you. Since that time many have been caught, brought in, and become very domestic. I had a male and female for several months, one of them (the male) eat bread, and was particularly fond of tea. I was in great hopes he would have lived till I had an opportunity of sending him to you, but an unaccountable accident happened to him & he died soon after. The skeleton of the latter I have sent to Mr. Home, and both their skins are in a box with some specimens directed to you which Captain Woodruff of the Calcutta is so kind as to say they will be safe delivered.” (Mitchell Library, Banks Papers, CY3008, 327-8)

Unfortunately one of the animals died before he could send it to England, just as it seems the Truman/Inman pair failed to board the ship alive, for it was not until 1880 that Londoners saw their first live Koala. Paterson did send two skins to Banks and a male skeleton to physiologist Everard Home of the Royal Society. This letter is significant for a number of reasons. Firstly, it points to the original collector of the first Koala to reach Sydney, namely Paterson’s “Capt. in the regiment.” This could have been either Captain Edward Abbott or Captain Anthony Fenn Kemp of the New South Wales Corp (HRNSW, 5). Abbott was based at Parramatta and outlying districts and was present in the Colony during the time of the 1803 discovery and the writing of the letter in March 1804. He therefore seems the most likely candidate for the unnamed captain who shot or otherwise obtained a Koala from Hat Hill between June-August 1803. Perhaps the aforementioned Sarjeant Packer accompanied him on the trip, or Robert Brown's convict assistant Joe Wild. We are forced to engage in such conjecture due, in part, to the Duke of York’s 1801 proclamation banning military involvement in exploring or scientific expeditions, and the Barrallier incident of late 1802. Paterson would have been required to keep his own activities in the area of natural history collecting secret during 1803. However his ongoing interest, and the scientific need to locate and fully describe this new Australian animal, were undoubtedly overriding factors. Paterson was also a friend and associate of Robert Brown, with the latter developing a close relationship with him whilst in the Colony. It is clear that the Koala specimens seen by Brown and figured by Bauer were the ones acquired by Paterson, though there were obviously others being brought to Port Jackson at the same time. It is also interesting that Paterson should be so critical of the Lewin drawing, suggesting that he had seen the much more accurate and true to life depictions by Bauer, an infinitely better artist.

The Paterson letter of March 1804 is an important pointer to the likely date upon which his description of the Koala was sent to Everard Home in London. A section of this letter was subsequently published within the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society during 1808 as part of Home’s paper on the reproductive organs of the Wombat, read to the Society on 23 June. Paterson's brief note represents the first published scientific description of the Koala. Issued almost five years after the discovery, there is no explanation for the delay in bringing it to public notice in England, though the then elderly Sir Joseph Banks' reticence at promoting investigation of the animals of Australia over the plants was possibly a factor. The relevant section from Home's first published account of the animal reads as follows:

“The Koala is another species of the Wombat, which partakes of its peculiarities. The following account of it was sent to me some years ago by Lieutenant-Colonel Paterson, Lieutenant-Governor of New South Wales.

“The natives call it the Koala Wombat; it inhabits the forests of New Holland, about 50 or 60 miles to the south-west of Port Jackson, and was first brought to Port Jackson in August 1803. It is commonly about 2 feet long and one high, in the girth about one foot and a half; it is covered with fine soft fur, lead-coloured on the back, and white on the belly. The ears are short, erect, and pointed; the eyes generally ruminated, sometimes fiery and menacing; it bears no small resemblance to the bear in the fore part of its body; it has no tail; its posture for the most part is sitting. The New Hollanders eat the flesh of this animal, and therefore readily join in the pursuit of it; they examine with wonderful rapidity and minuteness the branches of the loftiest gum trees; upon discovering the Koala, they climb the tree in which it is seen with as much ease and expedition as an European would mount a tolerably high ladder. Having reached the branches, which are sometimes 40 or 50 ft. from the ground, they follow the animal to the extremity of a bough, and either kill it with the tomahawk, or take it alive. The Koala feeds upon the tender shoots of the blue gum tree, being more particularly fond of this than of any other food; it rests during the day on the tops of these trees, feeding at its ease, or sleeping. In the night it descends and prowls about, scratching up the ground in search of some particular roots; it seems to creep rather than walk. When incensed or hungry, it utters a long, shrill yell, and assumes a fierce and menacing look. They are found in pairs, and the young is carried by the mother on its shoulders. This animal appears soon to form an attachment to the person who feeds it.

“A specimen of this animal has since been sent to me in spirits; the viscera had been removed, but the male organs of generation, and the structure of the limbs, were the same as in the wombat. There was no subdivision of vessels in the groin as in the tardigrade animals.” (Home 1808)

In is unfortunate that Robert Brown, then back in England, did not respond to the Home article with the publication of his more detailed description of the Koala, alongside the drawings of Bauer. Iredale and Whitely (1934), in noting this paper by Home, state that it “refers to the animals brought in by the natives to Paterson” but there is no reference therein to Paterson having acquired the animals through this means. We know that he used an unnamed soldier to assist with his collecting. It is also obvious that local Aborigines were involved in the process as well, though we have no specific details of who they were. The Iredale and Whitely paper is an important and much referenced document on the scientific discovery of the Koala. Unfortunately some of the unreferenced statements contained therein cannot be substantiated, and subsequent authors have repeated and embellished them (Troughton, 1964; Phillips, 1990). In light of the information presented in this paper, a clearer picture is revealed of events surrounding the European discovery of the Koala during 1802-4.

--------------------

7. Summary

In summary, it would appear that, following Barrallier’s despatch of the two Koala paws in alcohol to Governor King at the end of 1802, the hunt was on for a complete specimen. A search began in June 1803, involving Aborigines, convicts and members of the military. The first Koalas arrived in Sydney that August, having been acquired at Hat Hill by Lt. Governor William Paterson’s collector, who was possibly Captain Edward Abbott, perhaps assisted by Joe Wild. The initial specimens were a mother and two babies (one dead), though other animals were soon secured. These included adult males, both living and deceased, the latter having been shot or died as a result of captivity. Brown and Bauer had access to the original mother and child, and also to a later deceased specimen which Bauer figured and which Brown most likely dissected. Colonel Paterson subsequently acquired a pair, as did a Mr James Truman (or Inman), who attempted to despatch the animals to England in September. Whilst their exact fate is unknown, we know they did not make it there alive. Governor King obtained the services of the resident artist John Lewin in preparing a watercolour drawing of the animals, with the initial work sent in haste to Sir Joseph Banks in England during September 1803. In March of 1804 Paterson sent Banks two Koala skins, and a skeleton with a partial description to Everard Home. As already noted, Bauer’s exquisite drawings of the Hat Hill Koalas were not published at the time. A set of finished watercolour drawings were prepared by him around 1811. Bauer returned to Vienna in 1814, with his original pencil sketches, and the finushed watercolour drawings most likely remained in Robert Brown's possession until they were eventually passed on to the Natural History Museum, London, in 1843 (Norst, 1989). Reproductions of Bauer's Koalas first appeared in Stern (1960) and were publically exhibited in Australia during 1997 (Watts et al., 1997).

Brown's initial identification of the Koala as a species of Wombat (Didelphis coola ) carried through into Home’s 1808 published description of the animal, based on the information and skeletal material sent to him by Paterson. At some point William Bullock, goldsmith of Liverpool and, from 1809 owner and operator of a prominent London museum, obtained two preserved Koalas. The eighth edition of A Companion to Mr. Bullock's Museum (1810) noted that two of the animals were included in his London collection - an adult and baby. These may have been prepared from the skins sent to Banks by Paterson in March 1804, as it is known that Bullock obtained Australian material from him, including items from the Cook expeditions. It is also possible that the animals may have been connected with the Truman/Inman specimens sent to England around September 1803, though there may be any number of unknown and unnamed sources supplying the British and European market in the years 1804-10.

In May 1810 a part of George Perry's Arcania was issued, containing the first engraved image of the Koala, taken from one of Bullock's mounted specimens, along with a detailed scientific description allocating the name Bradypus Koalo, or New Holland Sloth, to the animal.

|

| Koalo, or New Holland Sloth, engraving, G. Perry, Arcania, London, 10 May 1810. |

The animal was subsequently used by the artist Howitt on 1 April 1812 to produce an engraving which appeared in A Companion to the London Museum and Pantherion (1814), the 17th edition of the guide to Bullock's museum. By this time it had become elongated in the hind section due to the forces of gravity and the method of mounting. The fact that Bullock's taxidermist had most probably never seen a live Koala would have made his task all the more difficult.

|

| Koala, engraving ( Howitt, 1812). Published in A Companion to the London Museum and Pantherion, London, 1814. |

William Bullock's London Museum was a large and very popular venue located in the middle of London, providing exposure for this newly discovered Australian animal. It included artefacts from the Pacific, including material formerly the property of Captain Cook.

During 1814 French naturalist H.M. de Blainville visited London, and upon observing a specimen of the Koala - perhaps in Bullock's Museum - he allocated it a new generic name Phascolarctos, from the Greek for pouched bear. When Blainville published his description in July 1816 he noted that the animal he had seen was from the "Vapaum" [Nepean] River region of New South Wales. Also during that same year the great French zoologist Baron George Cuvier published a brief description of the Koala within his multi-volume Règne Animal. An engraved plate of the Koala appeared in volume 4, issued during 1817. Therein it was portrayed as a tiger-like animal, walking on all fours.

|

| Le Koala, engraving, G.Cuvier, Règne Animal, Paris, 1817. |

The origin of the drawing is not known. It is clearly not based on the Lewin or Bauer depictions, though a French reference from 1840 states that it was taken from a drawing obtained by Cuvier (Iredale and Whitely, 1934). The Baron merely designated the animal "Le Koala" in 1816-17. Iredale and Whitley ascribe type genus and species status to Cuvier's description and illustration.

The German zoologist G.A. Goldfuss used the Cuvier description and illustration to allocate a new genus and species to the Koala in 1817 - Lipurus cinereus. Perry, in his 1810 description, had commented that in regards to the Koala, "the general colour [is] cinereous, mixed with a brown tint" and it is perhaps from this that Goldfuss had obtained his species name. He went on to redescribe the Koala in 1819 and rename it in 1820 Marodactylus cinereus. However, as Blainville had precedence over the genus naming (Phascolarctos), and Goldfuss over the species name (cinereus), A. Waterhouse in his Natural History of Mammals (1821) finally identified the animal as Phascolarctos cinereus. This name still stands, though Phascolarctos Koala commonly appeared throughout the 1820s and the genus Lipurus was used in Europe through to the 1840s.

When Cuvier's definitive work was published in English in 1827 it contained an engraved image of the Koala based on Lewin's drawing of September 1803. The actual engraving was dated 1824 and included the annotation:

"from a drawing made in New Holland by Mr. Lewin. It inhabits the banks of the river Vapaum, in New Holland."

This image was used in subsequent editions, whilst it was copied for other assorted publication both in England and abroad. New images of the Koala appeared in the Penny Cyclopedia (1836) and as part of a series of articles in The Saturday Magazine issued during the same year by a surveyor working in Australia, William Romaine Govett. When the famous natural history artist John Gould visited Australia during 1839-40 he took images of the Koala which later appeared in his Mammals of Australia (1863).

|

| Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus, coloured lithograph, J. Gould, Mammals of Australia, London, 1863. |

There are obvious similarities between the Gould and Bauer images, especially in the placement of the mother and child. We also know that Gould had seen some of Bauer's completed watercolours of Australian birds and animals in the British Museum, having been assisted in this process by Robert Brown (Wheeler and Moore, 1994). It must be said that whilst the finish coloured lithographs published by Gould in 1863 are quite stunning, the actual depiction of the animals is somewhat similar to John Lewin's 1803 watercolours, presenting the facial features of the animals as rather pointed. Bauer's Koala drawings are undoubtedly of a higher standard, both artistically and scientifically. In the absence of extant preserved physical type specimens for the Phascolarctos cinereus, Bauer's original August 1803 drawing and subsequent finished watercolours of the Hat Hill animals must serve that purpose, alongside Robert Brown’s description from 1803. The skins and skeleton sent to England by William Paterson in March 1804 also most likely relate to these works, though it is unknown if they survive.

-------------------

8. Timeline - Scientific Discovery & Taxonomic Description of the Koala

The following timeline chronicles the complex and convoluted taxonomic description of the Koala, specifically during the period 1798 - 1863. This listing has been substantially compiled from Iredale and Whitely's descriptive history (1934) and G.M. McKay's detailed taxonomy (1988). The Timeline includes reference to manuscript and published descriptions of the Koala, along with early illustrations in the form or pencil sketches, finished watercolours, plus lithographic and engraved prints.

1798

* Cullawine or sloth. John Price, January 1798. Manuscript journal. Mention only of an animal seen near Bargo / Mittagong, south-west of Sydney. Manuscript, published 1897 [refer below].

1802

* Colo or monkey. Ensign Francis Barrallier, 9 November 1802. Manuscript journal. Mention only of parts of a dead animal seen and collected south-west of Sydney, in the area of the Nepean River.

1803

* Didelpis coola. Robert Brown, August 1803. Type specimen(s) located at Hat Hill, Illawarra, 80 kilometres south of Sydney. Described in Brown's manuscript notes, with reference to the drawings of Ferdinand Bauer. Notes compiled and annotated after 1814 from work books and other contemporary records.

* Ferdinand Bauer, 'Koalas, Phascolarctus cinereus .... from the South of Port Jackson, August 15, 1803', pencil sketch, 51.8 x 74.5cm, Sammlung Bauer B-SS/1, Natural History Museum, Vienna. NB: The original sketch is dated 1803, however the Latin name dates from 1821.

* [Unknown / unnamed species], similar to Wombat. Anonymous, Sydney Gazette, 21 August 1803. Description of first animals brought to Sydney.

* [Female Koala plus young baby]. Drawing by Ferdinand Bauer, Sydney, August- September 1803. Watercolour on paper, 51 x 33 x 50.6cm, Museum of Natural History, London, Bauer Zoological No.5. Illustrated Stern, 1960; Mabberley, 1985, plate 14, colour; Norst, 1989, colour; Phillips, 1990, p.16, colour; Watts et al., 1997, plate 53, colour.

* [Female Koala plus young baby on back]. Drawing by Ferdinand Bauer, Sydney, August- September 1803. Watercolour on paper, 51 x 33.8cm, Museum of Natural History, London, Bauer Zoological No.6. Illustrated Watts et al., 1997, plate 51, colour.

* [Koala head – 2 views]. Drawing by Ferdinand Bauer, Sydney, August- September 1803. Watercolour on paper, 51.1 x 33.3cm, Museum of Natural History, London, Bauer Zoological No.8. Illustrated Watts et al., 1997, plate 54, colour.

* [Koala skull and claws]. Drawing by Ferdinand Bauer, Sydney, August- September 1803. Watercolour on paper, 51.2 x 33.7cm, Museum of Natural History, London, Bauer Zoological No.9. Illustrated Watts et al., 1997, plate 52, colour.

* [Two Koalas on branches]. Drawing by Ferdinand Bauer, Sydney, August- September 1803. Watercolour on paper, 51 x 33.8cm, Museum of Natural History, London.

* Didelpis Cooloo or Didelphis Coola, species of Wombat. Robert Brown, Sydney, September 1803. Letter. Brief description plus mention of figuring by Ferdinand Bauer and John Lewin.

* 'Coola, an animal of the oppossum tribe from New South Wales'. Watercolour drawing by William Lewin, Sydney, September 1803. British Library. Reproduced in Baron Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom (1827).

* Cola. George Caley, 18 September 1803. Letter. Mention only.

* Koolah. Anonymous, Sydney Gazette, 9 October 1803. Mention only of eating habits.

1804

* Cooler, William Paterson, Sydney, 10 March 1804. Letter. Mention only of how specimens obtained.

* Koala Wombat. William Paterson, Sydney, ? 10 March 1804. Letter to Everard Home – reproduced in part in Home (1808). Description.

1808

* Koala or Koala Wombat, Everard Home, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 1808, p.304. Description by Home based on the text provided by William Paterson.

1810

* Koala. Anonymous, A Companion to Mr. Bullock's Museum, 8th edition, London, 1810, p.16. Reference to a specimen on display.

* Bradypus Koalo, or New Holland Sloth, George Perry, Arcania, or, The Museum of Natural History: Containing the Most Recent Discovered Objects Embellished with Coloured Plates, London, May 1810. First published illustration of a Koala – figured from a stuffed and mounted specimen in the possession of Mr. Bullock of London, who had two specimens – an adult and a young one. It is therein described: "Amongst the numerous and curious tribes of animals, which the hitherto almost undiscovered regions of New Holland have opened to our view, the creature we are now about to describe stands singularly pre-eminent. Whether we consider the uncouth and remarkable form of its body, which is particularly awkward and unwieldy, or its strange physiognomy and manner of living, we are at a loss to imagine for what particular scale of usefullness or happiness such an animal could by the great Author of Nature possibly be destined... As Nature however provides nothing in vain, we may suppose that even those torpid, senseless creatures are wisely intended to fill up one of the great links of the chain of animated nature..." Reproduced: Iredale & Whiteley, 1934, p.64, b/w; Stanbury & Phipps, 1980, p.26, b/w; Phillips, 1988, p.16, colour.

1812

* Koala. Engraving image by Howitt of a stuffed Koala on a branch, dated 1 April 1812. Published in Anon. (1814). Figured from the stuffed and mounted specimen on display in Mr Bullock's Museum, London. Illustrated Iredale & Whiteley, 1934, p.66, b/w.

1814

* Koala. Anonymous, A Companion to the London Museum and Pantherion, 17th edition, London, 1814. Includes engraved image dated 1 April 1812 from the stuffed and mounted specimen in Bullock's Museum. Illustrated Iredale & Whiteley, 1934, p.64, b/w.

1816

* Phascolarctos, H.M.D. de Blainville, ‘Prodrome d'une nouvelle distribution systematique du regne animal', Bulletin des Sciences par la Societie Philomathique de Paris , Paris, July 1816, 113-124. Description of a specimen from the Nepean River area, New South Wales, seen in London in 1814. Allocation of new genus Phascolarctidae.

* Les Kaola. Baron G. Cuvier, Règne Animal, Paris, 1, 1816, p.184. Description, plus illustration in volume 4 (1817).

1817

* Le Koala. Baron G. Cuvier, Règne Animal, Paris, 4, 1817, plate 1. Engraved plate of a Koala walking on four legs. Illustrated Iredale & Whiteley, 1934, p.67, b/w; Phillips, 1990, p.17, b/w.

* Lipurus cinereus, G.A. Goldfuss, Schreber's die Saugethiere, in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen. Fortgesetzt von A. Goldfuss, 1817. Genus and species naming of the Koala, based on Cuvier's description and illustration of 1816-1817.

1818

* Opossum (Didelphis). Allan Cunningham, Journal, 9 November 1818. Description of a Koala in the Illawarra district.

1819

* Lipurus cinereus, G.A. Golfuss, in Lorenz Oken, Isis, 1819, p.271. Renaming by Goldfuss.

1820

* Morodactylus cinereus, G.A. Goldfuss, Handbuch der Zoologie, Abteilung II, J.L. Schrag, Nurnberg, 1820, p.445. Replacement name for Lipurus cinereus.

* Phascolarctos fuscus, A.G. Desmarest, Encyclopedie Methodique - Mammalogie..., Paris, 89, 1820, p.276. Desmarest felt that the animal described as brown was not the same as the grey one and therefore allocated a new, second species name.

* Le Koala ou Colak, A.G. Desmarest, Nouvelle Dictionare d'Histoire Nat., Paris, 17, 1820, p.110, tab. E.22, fig.4. Reproduces illustration from Cuvier (1817).

1821

* Phascolarctos cinereus, Waterhouse, Natural History of Mammals, vol. I, p.25. This is the definitive naming of the Koala.

* - Gray, Annals of Philosophy, 1821.

* Koala. H.R. Schrinz, Das Tierreich, J.G. Cotta'schen, I, 1821, p.265.

1824

* Coola or Kaola. Engraved plate ‘The Coola or Kaola. publ. 1824.' Published in the English edition of Baron Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom , 1827. Therein annotated “From a drawing made in New Holland by Mr. Lewin. It inhabits the banks of the river Vapaum, in New Holland.”

* Lipurus cinereus, Lithographed plate by Carl Joseph Brotdmann, in Heinrich Rudolf Schinz, Naturhistorische Abbildungen der Saeugethiere (Natural History of Mammals), Zurich, Switzerland, 1824. After the original drawing by John Lewin, 1803.

1826

* Wombat of Flinders, Knox in Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, 1826, p.111.

* Colak ou Koala. Isidore Georffroy St. Hilaire, Dict. Class. Hist. Nat., 9, February 1826, p.133. Reproduction of Blainville's description. “On le nomme Colak ou Koala dans le voisinage de la riviere Vapaum dans la Nouvelle-Holland.” [Translation: It is named Colak or Koala in the vicinity of the Nepean River in New Holland.]

* Koala Brun (Desm.) Male [with] Koala Brun. (Desm.) [Skeleton] [Two engravings of the Koala Bear, one of his skeleton]. Paris: Gide, 1853. Two exquisite stipple engravings with period hand color of the koala bear, as well as the koala skeleton, from Dumont D'Urville's "Voyage au Pole Sud et Dans l'Oceanie..." The French voyages in this period benefited from the French expansive world view, that saw artists & scientists accompanying the sailors on French voyages of exploration, recording scientific detail and assembling natural history collections. Jules Dumont D'Urville visited Australia twice, 1826-29 & 1837-40. His account of the second voyage was published in 1842 (text volumes); 1846 (atlas) and 1853 (natural history plates). At no time during Dumont D'Urville's second voyage did they visit a koala habitat in Australia (they visited the attempted settlement at Port Essington in Northern Australia, Torres Strait and Tasmania) so it is conjectured that this drawing was perhaps made during the first voyage of 1826-29. Illustrated below.

1827

* Phascolarctos flindersii, R.P. Lesson, Manuel de Mammalogie, Paris, 15, May 1827, p.221.

* Phascolarctos koala, J.E. Gray in E. Griffith, C.H. Smith & E. Pigeon, Baron Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom, London, 5, 1827, p.205.

* Phascolarctos koala. J.E. Gray in E. Griffith, C.H. Smith & E. Pigeon, Baron Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom, London, 2, 1827, p.50. Plate ‘The Coola or Kaola publ. 1824.' Annotated “From a drawing made in New Holland by Mr. Lewin. It inhabits the banks of the river Vapaum, in New Holland.”

* Lipurus cinereus, The Natural History of Mammals, 1827. Lithograph by Carl Brodtmann, after original drawing by John Lewin (1803). Illustrated below.

1830

* Koala subiens. G.T. Burnett, 'Illustrations of the Quadrupeda, or Quadrupeds: being the arrangement of the true four-footed beasts indicated in outline', Quarterly Journal of Science, 2, 1830, p.351.

1834

* Liscurus Koala. H. McMurtrie, Baron Cuvier's The Animal

Kingdom, London, 1834, p.78. Description, plus engraved view with (i) Adult

plus cub (facing right), (ii) Skull. In later editions (1863) skull omitted and

figure redrawing, with animals facing to left. Illustrated below.

1836

* Native Bear. Engraving in Penny Cyclopedia, Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, London, 14, 1836, p.461. “We are enabled to give figures of the parent and young, taken by the kind permission of a friend, from a very accurate and beautiful drawing executed from the living animals, the first that were known in the colonies. The native name “Koala” is said to signify “Biter.” There are old and young stuffed specimens in the British Museum, and a stuffed specimen (Mr. Caley's) in the Museum of the Linnean Society.”

* Monkey. William Romain Govett, ‘On the animals called “Monkeys” in New South Wales', The Saturday Magazine, London, 9(288), 31 December 1836. Detailed description plus engraved sketch by William Romaine Govett of a Koala on a tree. [Koala ]. Illustrated Iredale & Whiteley, 1934, p.64, b/w; Phillips, 1990, p.18, colour.

1838

* Lesson, Complements de Buffonn, 1, 1838, plate. Illustrated with copy of a figure previously published, as no specimen was available in France.

1840

* Anonymous, Dictionnaire Pittoresque d'Historie Naturale, 4, 1840, p.300. Comment: George Cuvier, possessing the drawing of another animal also called the Koala, and from the same region, thought he was bound to make a Phascolarctos of it, although he asserts that is lacks a thumb, etc.

* Anonymous, Dictionnaire Pittoresque d'Historie Naturale, Atlas, plate 280, figures 1 (grey Koala with a young on its back) & 2 (Native Bear climbing up a branch).

1841

* Phascolarctos fuscus, Native of Australia. Koala engraving c1841, by Lizars, William Home Lizars. Steel engraving by William Home Lizars (1788-1859) after the drawing by William Dickes (1815-1892), for Marsupialia or Pouched Animals by George Robert Waterhouse (1789-1856). The small engraved nature portrait was accentuated by hand-colouing of the animal only, leaving the engraved background habitat uncoloured. Published in Edinburgh circa 1841 for The Naturalist’s Library 'Mammalia' by Scottish naturalist, Sir Willliam Jardine (1800-1874).Illustrated below.

1842

* Koala. Hombron and Jacquinot, Voyage Pole Sud sur …. L'Astrolabe et La Zelee, Mammalia. Plates 17-18. Figures of the Koala.

1843

* Lipurus koala. Okens allgemeine Naturgeschichte fuer alle Staende, Stuttgart, Hoffman'sche Verlags-Buchhandlung, 1843, plate 088. Engraved plate of animals, including the Australian Koala. Figure after image published in Cuvier (1834).

1852

* Koala. Drawing by the Reverend Francis Orpen Morris, 1852. Wood engraving print.

1860

Phascolarctus mauve + skull, engraving, 1860.

1863

* Koala, Phascolarctos cinereus, John Gould, Mammals of

Australia, London, 1863. Description plus 2 illustrations - 2 coloured

lithographs. Illustrated above in text.

1867

* Koala, [Animals], Traugott Bromme, Sweden, 1867. Lithograph, possibly after original drawing by Ferdinand Bauer. Illustrated below.

1870

* 'Zoologie', wood engraving, Germany, 1870. Collection of Australian animals, including the Koala. Illustrated below.

1870

* Charles Night, Pictorial Museum of Animated Nature, 1870.

Wood engraved plate, after drawing by Ferdinand Bauer. Illustrated below.

1882

* Koala (Phascolarctos cinereus). Original German image from 1882. Details unknown. Illustrated below.

1923

* Phascolarctos cinereus adustus, O. Thomas, 'On some Australian phalangeridae', Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 9(11), 1 February 1923, p.246.

1934

* T. Iredale and E. le G. Troughton, 'A checklist of the mammals recorded from Australia', Memoirs of the Australian Museum, Sydney, 6, 1934.

1935

* Phascolarctos cinereus victor, E. le G. Troughton, 'The southern race of the Koala', Australian Naturalist, Sydney, 9, September 1935, pp.137-40.

1988

* Phascolarctidae, G.M. McKay, in D.W. Walton (ed.), Zoological Catalogue of Australia - Volume 5: Mammalia, Canberra, 1988, 51-2. Comprehensive taxonomy of the Australian Koala.

---------------------

|

| Robert Brown (1773-1850), photograph c.1850. |

9. Robert Brown at Hat Hill 1804

Robert Brown's precise identification of the first live Koalas to arrive in Sydney having come from Hat Hill is, as we have seen, significant. His association with that location was not to end with the discovery of the Koala there during June-September 1803. In fact, he was set to visit the area the following year.

Brown had arrived in Australia at the end of 1801 with the Investigator expedition. Between his reaching Sydney on 9 December 1801 and final departure for England on 23 May 1805 Brown was involved in a circumnavigation of the continent and a number of inland excursions, including visits to Van Dieman’s Land (Tasmania), Port Phillip (Victoria), the Hunter and the hinterland around Sydney (Vallance, 1990). His time in New South Wales was therefore broken up and of varying duration (Table 1), though in total it amounted to more than 18 months. It apoears that his periods of residence in Sydney between 1802-1805 were as follows:

- 9 May – 22 July 1802

- 9 June – 4 December 1803

- 21 August 1804 – 23 May 1805

During his excursions out of Sydney, Brown was variously accompanied by the expedition’s botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer, local resident botanist George Caley, the convict guide Joseph Wild, and others including members of the military, free settlers and Aboriginal guides. Precise records of his activities whilst in New South Wales can be gleaned from diaries, letters and scientific notes. These have been collated, but unfortunately the records are fragmentary (Vallance, 1990; Vallance et al., 2002). The fact that Brown did not keep a detailed account of his movements whilst resident in Sydney makes the task of reconstructing his visits all the more difficult.

Between 1802-05 he was involved in the colkection of thousands of plant and animal specimens, the majority of which were identified, drawn, preserved, prepared for shipment to England, named and otherwise dealt with by him and Bauer. Following Brown's return to England in 1805, over the following five years he listed and identified some 4,200 distinct species of Australian flora, comprising a third of those at present known (Mabberley, 1985). His descriptive work on animals largely went unpublished, or was completed by colleagues. This accounts, in part, for his failure to publish his Didelphis coola description alongside Bauer's figures.

In 1827 an article was published in the Transactions of the Linnean Society, London, identifying type specimens of the Australian native bird Spine-tailed Log-runner (Orthonyx temmincki) with the comment that:

"The Society's specimen was presented to them by Mr. Brown, who met with it near Hat Hill in the year 1804" (Brown, 1827).

Another species, the 'Purple-breasted Pigeon' (Megaloprepia magnifica) was also identified as having been gathered by Brown nearby. It has been assumed that Robert Brown was brought to the Illawarra by the convict Joseph Wild (1759-1847), an associate of Charles Throsby, a skilled bushman and assigned to assist Brown during his stay in the Colony. When Reverend James Backhouse and his companion George Washington Walker visited Charles Throsby Jnr. at Moss Vale in October 1836, they met with the then elderly Wild. Backhouse recorded the following in his diary:

"6/10 mo: 5th day 1836 [Thursday 6 October 1836]. Furnished with horses by C. Throsby and attended by an aged man named Jos[ep]h Wyld as a guide we proceeded to Black Bob's Creek where there is a Road party..... J. Wyld was transported to this Colony in 1793 and has taken part in some of the remarkable changes in it: he was at one time in the employment of a person of the name of Humphreys who was subsequently Police Magistrate at Hobartown; he [Wild] accompanied Rt. Brown as a servant, in his botanical researches in NSW and VDL; and he discovered the fine tract of country we have lately visited, called Illawarra: he is now in receipt of a pension of 6d p diem from Govt. and having spent many years in the employment of the Throsby family is supported by C. Throsby and allowed the use of a horse and a gun with which he amuses himself: he is 73 years old...." (Beale et al., 1991)

The "Humphreys" referred to was Adolarius William Henry Humphrey, New South Wales government mineralogist, who also accompanied Brown on his visit to Tasmania between December 1803 - August 1804 (Vallance, 1981). In Backhouse's published account of his meeting with Wild, he noted that the latter had "discovered the district of Illawarra" and travelled to Tasmania with Brown (Backhouse, 1843). When Wild applied for a renewal of his ticket of leave on 6 August 1810 he stated that he was “Servant to Robert Brown, botanist” (Davis 2006). Even though this was five years after the scientist had left the colony and returned to England, the comment perhaps indicates that Wild was still in contact with Brown, and possibly engaged in collecting for him. There is no reference to Wild in Vallance's detailed exposition of Brown's Australian activities between 1802-5, though his convict status may account for the scientist's failure to make reference to his important work. The associated scant evidence of a visit to the Illawarra in 1803 to locate the Koala reinforces the difficulty of pinning down the activities of natural history collectors in the Colony during this period. In a similar vein, Bauer's servant Powell is practically invisible (Norst, 1989).

The 1827 statement regarding Brown's visit to the Illawarra in 1804 collecting birds stood unchallenged for over a century. It was reiterated in K.A. Hindwood’s 1938 article on the Spine-tailed Log-runner published in the Australian ornithological magazine The Emu. Likewise, in 1958 D. Gibson recorded in the Illawarra Historical Society Bulletin that Brown had collected the aforementioned type specimens at Mount Kembla. However, following some local debate during the sixties and seventies as to whether Cook’s Hat Hill was Mount Kembla or the nearby Mount Keira, in the Bulletin of July 1980 Norm Robinson stated that he was unable to find any evidence of Brown’s visit to the region in 1804. He therefore believed that another person had located the specimen of the Spine-tailed Log-runner. By October 1980, in a second article, Robinson went beyond the "lack of evidence" statement to state emphatically that the "indications are that [Brown] did not" visit Illawarra. No evidence was given in support of this statement.

Robinson and others, being unable to find corroborative evidence of Brown’s visit to the Illawarra region in the form of contemporary letters, diaries, journals or scientific records, rejected the original 1827 statement attributing the discovery of the birds to Brown. The author (Organ, 1989), disputed this inference and presented the published donor statement as evidence. Vallance (1990) noted that no Brown diary survives for the period June-November 1803, whilst information on the period August 1804 – May 1805 is scant. Brown did become ill during the latter part of his stay in the Colony, but up until 1805 he was quite active. It is therefore likely that he visited the Illawarra as recorded. He may, in fact, have been taken there by the soldier employed by William Paterson to collect specimens – the same soldier who Paterson claims first brought the Koala to Sydney. An excursion to the Illawarra, located just 50 miles south of Sydney, would not have been overly onerous, especially with the assistance of local Aboriginal guides who, afterall, knew the area intimately and regularly travelled between there and the penal colony to the north.

The absence of any precise record of the visit is possibly related to the 1801 decree barring the military from engaging in exploration. It is also possible that a scientific excursion to Hat Hill and the Illawarra, an unsettled and rather inaccessible area located so close to Sydney, would be kept secret from the convict population to discourage them from escaping there and seeking a hideaway in its lush forests. It therefore seems reasonable to abide by the evidence of the 1827 Linnaean Society article and support the statement that Robert Brown collected bird specimens himself at Hat Hill in 1804. Such a position should stand until evidence to the contrary is produced. The lack of additional corroborative evidence is no reason to dismiss the available evidence. We do know that Brown appropriated specimens collected by others, such as George Caley, but once again there is no direct evidence that this was the case with the Illawarra birds. It is clear that, for whatever reason, a number of important excursions to Hat Hill and the Illawarra occurred during 1803-4 in search of faunal specimens. By 19 July 1807 the Sydney Gazette had no qualms about reporting that bird collectors had recently visited the Five Islands (Illawarra) and brought back two new birds. But such was not the case four years earlier when Robert Brown and Ferdinand Bauer were collecting and describing from their base in Sydney. Whilst Brown makes reference to Hat Hill in regards to the discovery of the Koala and two new bird species, there is no known reference to the locality amongst the thousand of flora specimens he acquired from Australia. This is surprising as Illawarra was the closest region to Sydney containing sub-tropical rainforest, with a variety of flora not to be found amongst the dry forests around Sydney. It was investigated extensively by the botanist Allan Cunningham during a number of excursions there between 1818-28 (McGinn, 1970). Cunningham also encountered a Koala there in 1818. The region therefore presented a rich collecting ground for natural historians.

--------------------

10. Acknowledgements