Bundanoon - Notes on Aspects of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage - Part 1 to 1850

|

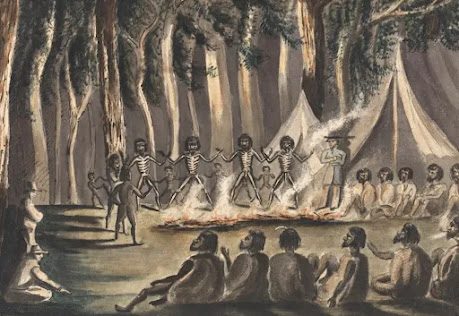

| Robert Hoddle, Bundanoon escarpment c.1830. |

The township of Bundanoon, New South Wales, Australia, is situated on the traditional lands of the Dharawal (Tharawal) / Wadi-Wadi (Wodi-Wodi) and Gandagara (Gandangarra / Gundangarra) peoples. As in many other parts of Australia, it has been noted that, on the surface, there is no evidence of the rich Indigenous cultural heritage of Bundanoon, and no known surviving population of descendants of the original inhabitants. However, if one digs deeper, there is much to be found, including the presence of six families. The 'English' heritage of the town dominates due to the socio-economic reality of its present day primarily non-Indigenous population, arising out of more than two centuries of external immigration and the decimation of the Indigenous population (refer possible causes listed below). In general, only around 2% of the urban Australian population in regions such as the Southern Highlands identify as Indigenous, or of Indigenous ancestry. This blog attempts to reveal some of the ancient and more recent history of Bundanoon in regards to its First Nations people and their cultural heritage. As such, it aims to provide a resource for future study. Statements made herein, and points of conjecture, are such subject to correction and alteration.

Tribes & Languages - Bong Bong / Shoalhaven or Midthung / Tharumba?

According to research by Moss Vale historian Narelle Bowern (2018), during the earliest periods of European settlement (i.e., prior to the 1860s) the people about the Bundanoon region comprised members of what was then referred to - by Europeans - as the 'Bong Bong tribe' and 'Shoalhaven tribe', including some intermingling with peoples from the area to the west and north-west around the Wollondilly river, and to the south towards Goulburn, variously referred to as the Nattai, Burragorang or Gundangurra tribes. It should be noted that the Aboriginal people did not refer to themselves by these names prior to 1788, though the words themselves - apart from Shoalhaven - are Aboriginal and usually refer to specific localities, not tribal groupings. Europeans ascribed the term 'tribe' to Aboriginal people from specific areas in order to manage interactions and for purely administrative purposes. Also, tribal affiliations, sizes and names varied during the initial decades of white settlement as limits on access to traditional lands were impose and the number of people was diminished by disease, murder and loss of tradition.

|

| Language groups applied to the Bundanoon / Bong Bong area, circa 1976. |

It can be surmised from Bowern's research that the people of Bundanoon were more closely linked with Dharawal / Wodi Wodi (Shoalhaven tribe) and the so-called Bong Bong tribe, then with what is currently, and very broadly, defined as Gundangarra. This is also reflected in the famous Tindale map of Aboriginal Australia (Tindale 1974) wherein the boundary line between Dharawal and Gundungarra places much of the Southern Highlands in Dharawal territory. Unfortunately, the map included in the well-known Meredith (1989) biography of Moyengully, chief of the Gundungarra, extends the Gundungarra borders east towards the edge of the Illawarra and Shoalhaven escarpment, thereby excluding the Dharawal / Wodi Wodi association in regard to both language and cultural heritage. The status and makeup of the Indigenous population around Bundanoon as of 1788 (and prior) is largely unknown. However, it obviously changed dramatically over the next century, such that by the 1880s it appears that those surviving had moving into secluded areas such as the Burragorang Valley to the north, to the coast within the Shoalhaven and areas around Mount Coolangatta and Broughton Creek, or simply stayed where they were and blended in with the new non-Indigenous society.

|

| Illert language groups, circa 2021. |

Another theory has been proposed by Dr. Chris Illert within his publications, based upon a study of the Australian Aboriginal languages and what he calls proto-Australian (Illert 2013-2021). Illert has used his knowledge of early colonial word lists and grammar examples, and the reconstructed proto-Australian language, to define boundaries between various language (and tribal) groups based on that information. In the case of the Bundanoon area - highlighted by a green dot within the adjacent map - it lies near the boundary of what he has defined as the Midthung language (to the east) and Tharumba (to the west). This in some ways reflects the Tindale boundary between Dharawal (east) and the Gundangarra (west). Illert also places Bundanoon close to his Turuwul and Gundungarra language groups, with Wodi Wodi focused around the coastal Wollongong area. Whilst these divisions present a complex area of multiple Southern Highlands 'languages', in fact many of these are very closely associated and are closer to what Europeans know as dialects, rather than distinct languages. Communication between Aboriginal people of New South Wales was relatively straight forward due to these similarities, though this was also overlain with relevant customs associated with relationship to Country.

Country - the landscape

|

| Terrain around Bundanoon, showing gorges to the east and southeast, and flat land to the west. |

The area around Bundanoon is located approximately 600 metres above sea level on the edge of a flat, heavily wooded landscape known as the Southern Highlands. According to an unnamed source, this was a meeting and trading place for Aborigines over the millenia prior to the European invasion of 1788 and their subsequent dispossession. It is bounded on the east and southeast by steep escarpment cliffs and gorges leading down to the Illawarra and Shoalhaven coastal plain, on the west and north west by the Tarlo and Wollondilly rivers, and on the south west by plains stretching down to Marulan and Goulburn. A number of ancient pathways were focused around Bundanoon and used by the local people and visitors in their travels between the coast and highlands for ceremonial and familial events. For example, it appears that the banks of Bundanoon Creek formed one such pathway, especially when not in flood, leading down to the Kangaroo River and thereon to the Shoalhaven River. As noted above, close familiar and cultural ties appeared to exist between the people of the 1830s Bong Bong tribe and equivalent Shoalhaven tribe. The earliest non-Indigenous specific reference to the locality is dated at 1818 in association with Bundanoon Creek (refer map below). It is a record by an early explorer, Charles Throsby, who recorded the name of the place as bantanoon or pantanoon, and later into bundanoon. Based on Illert's language analyses, this can be interpreted as:

b ʊ (ra) :: n : d ʊ (la) : n u ɳ // ban : daia : noon

between : thing : someone's

i.e., where someone rests between places

|

| Route of Bundanoon Creek. |

Bundanoon Creek flows south-westerly from near Fitzroy Falls, past Meryla / Merlya plateau and mountain and the township of Bundanoon, and then turns ninety degrees towards the south-east, joining with the Kangaroo River and, in turn, the Shoalhaven River which flows easterly through the coastal plain towards Mount Coolangatta and Nowra. Bundanoon Creek is currently located within the Morton National Park. First Nations aspects of the park are described by the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service, which is responsible for management of Aboriginal cultural heritage in the State, alongside that of plants and animals:

Morton National Park is the traditional Country of the Yuin people. Several hundred Aboriginal sites have been recorded here and there are likely many more. The park's imposing mountains, particularly Didthul, are particularly significant in Aboriginal mythology, as is the majestic Fitzroy Falls. The park's plateau and surrounding country also contain sites of great importance to Aboriginal people, whose occupation of the area dates back over 20,000 years.

According to recent archaeological studies, Indigenous people have been present in Australia for at least 120,000 years, whilst their Dreaming speaks of a much longer, timeless period of occupation (Daley 2019). There are numerous archaeological sites in the Bundanoon area, the majority of which have not been subject to scientific study. The absence, therefore, of scientific evidence in the Bundanoon area does not disprove the presence of people for a period beyond 20,000 years, which is what is commonly applied to this part of eastern Australia. This lack is due to the fragility of such evidence and limited extent of research to date. Ongoing archaeological investigations are uncovering aspects of an extended timeline throughout Australia, especially from cave sites containing preserved skeletal material and artefacts. At present, much of this information, especially as it relates, or may relate, to the Bundanoon area is not publically available, or is scant and to be found within largely inaccessible consultant archaeological reports prepared for government departments, local councils, and private developers. Unfortunately, the need to protect historic sites, and certain aspects of cultural practice - though not all - has resulted in a general lack of knowledge amongst the wider non-Indigenous community of the rich cultural heritage of each and every part of the continent. Bundanoon is no exception. Some published historical records are available which refer to the Aboriginal cultural heritage of Bundanoon and the nearby area, and these are referred to below. For example, the following article reports on some Bundanoon rock drawings studied during 1908-9 by a scientist associated with the Australian Museum, Sydney:

* W.W. Thorpe, Aboriginal drawings in rock shelters at Bundanoon, N.S. Wales, Records of the Australian Museum, 7(4), 1909, 325-328. Investigations of the art within two rock shelters, including photographs and drawings.

1 - 1 A conventional animal or tail of lyre-bird

1 - 2 Undoubtedly an eel

1 - 3 Probably a "Goana" (Varanus sp.); or water lizard (Physignatus sp.)

1 - 4 A nondescript object, may be intended for a human being

1 - 5 A turtle

2 - 1 Aboriginal corrobboree - portion of six performers

2 - 2 Probably a frog with its mouth agape

2 - 3 Somewhat lacertilian in outline

2 - 4 Representation not identified

2 - 5 Fish

2 - 6 Tribal mark

2 - 7 Shell, shield or leaf?

2 - 8 Human being

2 - 9 Undoubtedly a shield

These ancient artworks are a mere sample of the rich cultural heritage associated with the once widespread Indigenous population of the Southern Highlands region of New South Wales. Burials, middens, scarred trees, rock art and stone tools are some of the items which, if they survive, point to the presence of people in the Bundanoon and adjacent area over an extensive period of time. In addition, print and pictorial records produced by the non-Indigenous arrivals in the area after 1788 add to the archival and archaeological record, which in turn continues to be discovered or rediscovered. The most comprehensive account of the traditional life of the Aborigines of the area around Bundanoon can be found within Bowern's Aboriginal People of the Southern Highlands, NSW (1820-1850). This publication contains mostly European first-hand accounts and reminiscences of encounters with the original inhabitants. A similar resource is the author's own Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1850, which also contains material of relevance to the Southern Highlands. The surviving picture is, unfortunately, fragmentary. It can be added to by the more fulsome accounts of the peoples around Sydney dating from 1788, and by the numerous publications which deal with issues such as the cultural practices and languages of the Aboriginal people of southeastern Australia, especially within those publications which appeared during the second half of the nineteenth century and first part of the twentieth. Extracts from some of these resources are reproduced below. The majority do not refer specifically to Bundanoon, but to the general region, as far north as Bong Bong / Moss Vale, west to the Wollondilly river, south to Tallong and east to the Shoalhaven gorges and Broughton Creek.

It should be noted that in the first century after Captain Cook and the Endeavour visited New South Wales (April-May 1770), no references have been found within the various newspapers and government gazettes to an Indigenous population in the Bundanoon area. We can, however, extrapolate, based on information concerning the peoples of the Bong Bong and Shoalhaven tribes. Causes for the disappearance of a significant Indigenous population are many and varied. Based on our knowledge of what happened in other in other parts of New South Wales during the first century of European settlement, and as a result of that settlement, they included the following:

- introduced diseases such as smallpox and tuberculosis, and a corresponding lack of access to proper medical facilities;

- loss of access to traditional lands for hunting, the gathering of food, and provision of shelter - properties were fenced off, dogs introduced and guns used to ward off natives peoples who were now deemed trespassers on their traditional lands;

- murder and massacre, on both small and large scale, and on occasion with the support of government and authorities viz. the nearby Appin massacre of 1816;

- interbreeding with Europeans, with the non-Indigenous gene dominating as squatters and farm hands took native women, often by force and rape;

- introduction of alcohol and changes to traditional plant-based diet;

- incarceration;

- removal from traditional lands;

- racist attitudes on the part of the non-Indigenous population, giving rise to a general, and more widespread, disinterest in their treatment or ultimate fate;

- lack of any Indigenous rights recognised by the British colonisers, either with regard to traditional lore or within the British legal system;

- and movement to other areas where Indigenous families could survive unmolested by the new arrivals. These areas were subsequently subject to control with the creation of the so-called Aborigines Protection Board in the late 1800s. Unfortunately, this body exacerbated the situation with the creation of a prison-like camp / mission regime.

As a result of the above, the decline in the Indigenous population across Australia continued apace during the first century of European settlement, leading to fears of extinction by the late 1800s. This only turned around almost a century later following calls for Aboriginal land rights from 1938, recognition as citizens of Australia in 1967, and, during the Bicentennial of 1988, exposure of the barbaric and extensive nature of the Frontier Wars, giving rise to an effort to pull back on systemic racism and discrimination of First Nations peoples. That effort continues to this day.

--------------------

1) The arrival of Europeans

1770

- Captain Cook claimed Australia for the British in 1770, following a visit to New South Wales during April-May of that year. It is likely that people of the Bundanoon area were told stories of Cook's visit to Botany Bay, arising out of the complex and ancient inter-tribal communication networks which existed throughout New South Wales and across Australia.

1788

- The First Fleet arrived at Sydney Cove in January 1788 and shortly thereafter escaped convicts and explorers began to travel south-west towards the Bundanoon region.

1798

- During January and March - April 1798 a small party which included John Wilson and John Price journeyed south from Sydney towards the area around Mittagong, climbing Mount Gingenbullen and then beyond to Marulan, encountering some local people (Bowern 2018). It was noted therein that the language / dialect of the people east of the Wollondilly appeared different to those to the west. Sources: John Price, Journey into the interior of the country of New South Wales,..... 1798, Historical Records of New South Wales, Sydney, 1898, 820-828; Cambage 1919; Jervis 1986.

- 28 January: Wilson kidnaps a young Aboriginal woman near Mount Gingenbullen. He eventually returns her to the local tribe (Jervis 1986).

1802

- 5 November: Explorer Francis Barrallier informed about Canabygle, during a visit to the Burragorang Valley.

1804

- 14 February: Botanist George Caley encounters Canabygle and members of his tribe in the area of Stonequarry. Canabygle appears to have been chief of the area around Mittagong, to the north and south, memorialised in the location Canabygle's Plain or Kannabygle's Plains, as described below:

- Cannabygle's Plain. — A name forgotten by the present generation is

'Cannabygle's Plains.' The Colonial Secretary, in a letter dated April 2, 1829, referred to 'a place on the Argyle Road...called Cannabygle, commonly known by the name of Little Forest'. This spot is in the Parish of Colo [Vale]. The place is named after an Aboriginal chief who was well known between 1800 and 1816. George Caley came across him during one of his exploratory journeys through the Cowpastures, when he was pointed out to the explorer. Caley spells his name as Cannabygal.

Cunningham [Cunningham's Journal, Mitchell Library] who passed through the spot, mentions that it ....was called by the aborigines Carra-bija plains.... Macquarie camped there on October 17, 1820, and calls the spot 'Kannabygle's Plains.' Cannabygal appears to have been one of the leaders in the native outbreak which occurred in 1816. He was killed near Broughton's farm in East Bargo.] (The Southern Mail, Bowral, 28 September 1937). NB: Cannabygle was killed in the Appin massacre, defending a group of women, children and old people. His body was strung up on a tree to instill fear in the surviving people, and his head was subsequently severed and sent to England for study. Little Forest is located south of present day Yerrinbool and north of Mittagong. (Jervis 1937)

1807

- John Warby explores south of Sydney along the Nattai river towards Bargo, but no further in the direction of the Southern Highlands (Jervis 1962, Bowern 2018).

1808

- 14 April 1808: Letter from naturalist George Caley to Sir Joseph Banks regarding the Illawarra and South Coast people. Source: Banks Papers, Mitchell Library:

...Sea coast natives said to visit the country near the hill [?the jib at Bowral]. The natives who inhabit this part are very numerous, savage, and hitch up their shoulders. Moowattin informs me that he has been told of this several times by different Natives. It is rather singular they should distort themselves in such manner. They give an account of 2 or 3 waterfalls being in this part. The vallies in this part convey the water into the river which I now call the Hawkesbury, but considerably higher up than what I have been. The trees growing in this part are different from those in the Colony. They say there is only one river to cross in all the way viz - the Nepean at Vaccary Forest. The tract of land between this hill & Vaccary Forest is called Borago [Bargo]. Moowattin before informed me that by what he saw of this country, he had reason to believe that it ran direct to this hill, and was a kind of scrubby forest land.

1814

- Hamilton Hume, John Kennedy Hume, John Kennedy and the Aboriginal man Duall reach Bong Bong and Berrima (Hume 1872, Liston 1988, Bowern 2018).

1815

- John Oxley moves cattle to Bargo, on the northern edge of the Southern Highlands.

1816

- John Oxley moves his cattle south towards west of Mittagong. Aborigines attack his hut. (Bowern 2018)

- Governor Lachlan Macquarie instigates a punitive campaign against the Aborigines in the area around the penal colony based at Sydney. Aboriginal people are killed, their custom made illegal and children taken away. According to Illert (2021), the chief of the Southern Tablelands people, extending from Picton south to Tallong, was Dual / Dewall. He was declared by Macquarie a wanted man and, as a result, was captured and exiled to prison in Tasmania (Organ 1990). It is for this reason that there is no chief of the tribe around Bundanoon after this date. It is also possible that Cannabygle was the chief of the local area and, as he was murdered by Macquarie's troops in the Appin massacre (see below), the same statement applies in regard to the loss of a chief of the Southern Highlands people.

- 25 March: Captain Schaw and his regiment marched south in search of Aboriginal people, camping at Callumbigles [Canabygle's] Plains near Mittagong.

1817

- Charles Throsby travels to Bong Bong and Sutton Forest with Hamilton Hume, John Rowley, Joseph Wild, and the Aborigines Bundell and Broughton (Sydney Morning Herald 1855, Bowern 2018).

1818

- The earliest European records of the area pertain to the Bundanoon Creek gorge which was explored in 1818 by Charles Throsby and a party of nine, with the assistance of local and other Aboriginal guides, Throsby was shown a route down to Jervis Bay, after twice setting off from near Bundanoon. According to an article by historian James Jervis published in The Southern Mail (Bowral) on 28 September 1937: BUNDANOON.— Throsby's Journal records the name "Bantanoon" (not Pantanoon) on March 29, 1818. A paper published in 1921 by R.H. Cambage describes some of these travels as follows (NB: relevant sections of the journal are also reproduced in full within Organ 1990):

- 13 March - Throsby and party guided to a spot at the head of Bundanoon Creek by locals, but unable to proceed down Bundanoon Valley due to swollen creeks, so they head south-west towards Marulan. On 26th they return to Bundanoon.

- 28 March - commence journey to Jervis Bay: ....We were met by Timelong and Munnaana who had been in search of us. They are two natives whom I have seen at Five Islands. Munnah is one of the two strangers whom myself, Colonel Johnson, his son George etc., met at the River Macquarie, Five Islands, the first time the Colonel was there, and which was the first time he had seen a white man. On our meeting them they had many jaged spears etc. but on my telling them through Bundell that the Governor required the Natives not to carry spears when with white people, they very readily consented to leave them, in fact they threw them away and assured me that the carts and other things we left would be safe. Meeting with the natives and being determined to travel with the horses as long as possible this evening, I thought it prudent to halt for a short time longer...

- 29 March - Bantanoon, 29th March, 1818 ... The two strange natives we met yesterday cannot be prevailed on by those two we have had with us to taste pork, say it is salt one of them Timelong is a robust man, very dark, with a very long beard, the other Munnana, a thin man, more of a dirty brick colour than black, with a beard only on the chin, on the upper lip and under the mouth it appears to be kept cut or most likely burnt off as is their custom, both are perfectly naked and not even provided with the most trifling covering for the night. ...About half an hour after we halted for the night several natives joined us most of whom I have seen at Five Islands, they were most women and children, only three men. I conceive them to be three familys the whole perfectly naked and slept round fires like as many dogs, they all approached us without spears or weapons of any sort except one stone axe and one small tomahawk.

- 30 March - Yarranghaa, March 30th, 1818. - Set out before breakfast to look at the creek towards its source found it coming out of very steep rocks, but from the inconsiderable stream think it does not extend any great distance.

- 31 March - Throsby and party reach the Shoalhaven River.

(Source: Charles Throsby, Journals & letters re exploring expedition with James Meehan to Jervis Bay, the Wollondilly, 3 March - 20 May 1818, Archives Office of New South Wales, Reel 6034, 9/2743 pp.9-76; Fiche 3276, SZ1046 pp.1-77).

1820

- Governor Macquarie camps at Kannabylge's Plains, near Mittagong.

1821

- November / December: Charles Throsby travels overland from Sutton Forest to Jervis Bay seeking to secure a usable route.

- James Atkins settles at Oldbury, Sutton Forest, adjacent to Mount Gingenbullen. The local Aboriginal name for the area was Tillynambulla (Forsyth & Murrell 2020).

Tillynambulla

dulʊ : ɲun : bulʊ

bent : something : flat = area of flat land around [the mountain Gigunbullen]

1822

- In 1822 James [Atkinson] and Errombee [his Aboriginal guide and friend] had spent severak weeks exploring from Sutton Forest to the coast, looking for grazing land and red cedar. One their return they bacame hopelessly lost in the impenetrable Shoalhaven gorges. When their provisions ran out, Errombee found bush tucker, roasting a goanna and harvesting honeycomb, but refused to eat anything himself for many days, saving the food for James. Errombee eventually managed to find the way back to Oldbury. James credited Errombee with saving his life (Forsyth & Murrell 2020).

1824

- As a result of explorations by Throsby and others, and a push by free settlers for government to provide access to land (NB: the Indigenous population had no rights or say in regard to this): Surveyor Harper was instructed to reserve 1200 acres of land, one boundary of which was to be 'Boon-doo-noon Creek,' by letter dated October 29, 1824. (Jervis 1937).

- March - April: Botanist Allan Cunningham travels through the Moss Vale district towards Goulburn.

1825

- Breastplate: Nemmit, Chief of the Sutton Forest Tribe, 1825, Mitchell Library, Sydney (Troy 1993, Bowern 2018).

1826

- Census of Aboriginal people records Bong Bong tribe - 67; Mittagong tribe - 10; and Nattai tribe - 62 (Jervis 1962).

* James Atkinson, An Account of the State of Agriculture and Grazing in New South Wales...., J. Cross, London, 1826. Includes illustrations by Atkinson of his travels with Aboriginal guides. Atkinson settled at Sutton Forest around this time.

|

| Sketches (prints) by James Atkinson of Sutton Forest (1826). |

Nominal List of native Blacks to whom Rugs were distributed in the District of Sutton Forest, County of Camden.

1 Neddy

2 Wollamorra

3 Jemmy

4 Jackio

5 Jacky Durong

6 Joe Wild

7 Johnny Pourwong

8 Charley Murrogood

9 Morrongally Pourodrang

10 Mongally

11 Jacko Collindilly

J. Fitzgerald J.P.

--------------

1827

- 7 March 1827: Letter from Charles Throsby to the Colonial Secretary re the subject of blankets and clothes for Aborigines of the Bong Bong (Berrima) district. Source:Archives Office of New South Wales, Colonial Secretary Correspondence 4/2045, letter 27/3651.

Transcription: Court Room, Bong Boong 7th March, 1827. Sir, No Magistrate but myself being here, I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 31st of March respecting the tribes of black natives to whom it is His Excellencys intentions to give blankets and stop clothing. The natives of these parts, particularly those of the more remote districts, not being much accustomed to wear clothing I am of opinion it would be most adviseable, for the present, to confine the donations to blankets alone, particularly as I have found by experience, that by commissions to be too liberal to them, has been attended with will rather than food. I would therefore respectfully recommend, that six, or even ten blankets be sent for distribution as a function, to the most usefull and deserving of the tribes who frequent these parts, the same number to those of the districts around where Dr Read resides, the same number to those of the districts around Limestone Plains, where the Honorable Mr Campbell has a station and the same number to those of the districts around where Mr McAlister resides. The Magistrates endeavouring to press on the minds of the most intelligent natives amongst them, that the donation is given as an inducement for good behaviour, and promises a reward for any public service they may perform (the example set by the natives about Liverpool in assisting the police will soon become known amongst those of the intension) and a prompt reward for any particular service, will have the best probable effect, by which means I have no doubt an efficient auxiliary police will be established, that by a little pains being taken, may become of great public benefit. I have the honor to be Sir, Your Obedient Humble Servant, Chas Throsby J.P. To: The Honble Alexr. McLeay Esqr., Colonial Secretary.

1828

- 12 May 1828: James Atkinson letter to the Colonial Secretary re past and present Aborigines at Sutton Forest.

Transcription: Sutton Forest 12th May, 1828. Sir, I have the honor to enclose herewith a return of the Black Tribes in this neighbourhood as called for in your letter of 29th April last. The Black Tribes in this district have greatly decreased in number within the last few years, and it is probable in a short time, will be nearly extinct; - When I was first acquainted with this country about 8 years since, the Sutton Forest Tribe consisted of at least 50 Men, Women and Children. They are now reduced to 18. I have the honor to be Sir Your obedt. humble servant Jas. Atkinson J.P. To: The Honble. Alexr. McLeay Esqr. Colonial Secretary

Sutton Forest 12th May 1828 - Return of the Black Natives in this neighbourhood shewing the particulars required in the Colonial Secretary's Letter of 29th April 1828

Name of Tribe - Sutton Forest Tribe

Usual place of Resort - Sutton Forest, Kangaroo Ground, &c.

No. of Men - 4

No. of Women - 9

No. of Children - 5

Blankets recommended to be given: Six. Other articles recommended: Three suits of slops. Red serge shirts instead of Cotton, Parramatta frocks in lieu.

Name of Tribe - Budjong Tribe

Usual place of Resort - Sutton Forest, Kangaroo 8 8 12 Ground, and the Banks of the Shoalhaven river in the County of Camden, and opposite side.

No. of Men - 8

No. of Women - 8

No. of Children - 12

Blankets recommended to be given: Eight. Other articles recommended: Six suits of slops, as above. This Tribe, although one of the most docile and peaceable possible have never had any Slops given to them. The principal person among them is Thomas Errombee an elderly man of the most quiet inoffensive disposition, and greatly respected by his countrymen. I beg to recommend that a plate should be presented to him inscribed "Errombee Chief of the Budjong Tribe." Jas. Atkinson J.P.

----------

- 11 August 1828: {AONSW, Col Sec Correspondence 4/2045, Letter 28/6848} Return of Aborigines of the Sutton Forest district.

Transcription: Sutton Forest District, 11th Augst, 1828. Sir, I beg to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 17th of May last regarding the distribution of fourteen Rugs to the Native Blacks in this neighbourhood who have recd. them in the manner directed. I also send you the Returns required. I have the honor to be, Sir, Your obt. Servt. Jas. Atkinson J.P. To: The Honble. Alex McLeay Esqre. Col. Secretary

A Return of the number of Native Blacks in the District of Sutton Forest Argyle County

Men 12

Women 15

Children Male 7, Female 5

Also a Return of the names of Native Black Men belonging to the District of Sutton Forest

Mallong

Errombee

Nullutt

Eting

Marroowallin

Hopping Joe

Carbon

Punkamundy

Jibberuck

Coonda

Nemmett

Deirong

Jas. Atkinson J.P.

----------

- 39 blankets distributed at Sutton Forest 1828 (Bowern 2018).

--------------

|

| T.L. Mitchell, Moyengully, 1 June 1828. |

- 31 May & 17 June 1828: Surveyor-General Thomas Mitchell supervises road construction between Mittagong and Marulan, west of Bundanoon. Some Gandarangara composed a cheeky song about the building of the road, perhaps with appropriate mimicry: Road goes creaking long shoes, Road goes uncle and brother white man see. A precise translation of the Road Song and associated Kangaroo Song are to be found in Chris Illert et al. (2021). Mitchell met with Moyengully, King Of Nattai (near Jellore, north-west of Mittagong) and one of Mitchell's 'earliest Aboriginal friends' (Meredith 1989). One of the men he recorded songs off was Billy Yerramagang. Men from the Gandarangara also acted as guides for Mitchell at the time (Baker 1998). For example, the following are extracts from Mitchell's diary notes and comments by Baker:

[Baker] One evening on the southern survey, Mitchell visited several Aboriginal families between Mittagong and Bowral and wanted one of the men to accompany his surveying party as a guide and interpreter but they were strangers to the land further south and frightened of the Aborigines living there. When Mitchell assured them that his party was well armed and that a guide would have nothing to fear, one of the Aborigines said, 'Ah, shoot de Buggers', but none would accompany him.

[Mitchell] Saturday May 31st - My horse having fallen into the water at Geloro (the native pronunciation of Jelore) was very weak and ill. I therefore walked to the top of Gibraltar (the hill on the North of Mr. Oxley's station at Wingecarabbee, called by the natives Bourel [now Bowral]) and there I find about 30 points observed from Geloro - and also the true situation of Bourel itself - by an angle in K. Georges Mount - one of the Caermarthen Mountains. I got angles also on the two hills under the Cockbundoon range, which are intended to be stations. This hill seems wholly comprised of the old red sandstone - which on the Western side takes regular forms like chrystals - and rests on granite, which appears on the lower extremities. - I returned in the evening well satisfied with the results of our Trigonometrical operations thus far, having succeeded in my attempt to connect Geloro & consequently the points to the South-wd. and with the Blue Mountains and the Lighthouse. After dinner, I learnt that the King of Nattai had "sat down" near my encampment, and in the evening I went to his fires; - there were several young men, at different fires - one black woman with her husband & child at another - and a widow with two children at another - Moyengully, the King, sat apart at another fire, he had a swelling on his right wrist and asked me for something to cure it - several native spears stood against a tree beside him, and as many more had been laid on the ground, but he got up and set these also against the tree. The young men, who lay between three fires were of a gay disposition that night, for they sang several songs, one was what they called the Bathurst song, another the Kangaroo song, - each line commencing "Kangaroo"-oo". - one commences, and the others join in the words etc - the old King added his bass voice occasionally to the strain. - One young fellow seemed one of the happiest beings I ever saw - without any covering but a skin over his hips, he lay on his belly on the ground - laughing heartily occasionally, and playing his legs carelessly about as he lay - his hair behind was filled with a profusion of black Eagles' feathers, which had a very appropriate & good effect - We wanted one of them to accompany us as a guide & interpreter to the Argyle country, but they all said they were strangers there. - They are at present much afraid of the Bathurst blacks, one of whom has been killed by the son of a Chief named Fry. - When we told them that as we were well armed, they would have nothing to fear, one of them said - "Ah - Shoot de Buggers"! -

[Kangaroo song]

|

| T.L. Mitchell Field Notes [extract].... 1828-30. |

Gubi gubi gay gin ganba regay

aei ganba geba gure gruen gay

Spear thrown but misses the Kangaroo

Arabun uma enimya aray inglay

wanumbula ingay enimili ingay

Can't find the kangaroo

gang ....

Mid me durga enga mamega gangeroo

abona tinnua eria cobua na nalluderra

luba

Kangaroo looks but sees nobody

Burranbunga windeginye uringango kuto oringa tumberin gang cumbiaga.

Kangaroo turns away and the native kills it.

----------------

[Road song]

Morud´ yerrab´ tundaj kmara

Morud´ yerrab´ tundaj kmara

(Road goes creaking long shoes)

Morud´ yerrab´ meniyonging white ma la

Morud´ yerrab´ meniyonging white ma la

(Road goes uncle and brother white man see.)

--------------

[Baker] When Mitchell reached Towrang, half way between Goulburn and Marulan, he enjoyed the companionship of a highly intelligent Aborigine called Primbrubna who agreed to travel with him for a while. In the evenings Primbrubna sang for his own pleasure and the entertainment of the white men. He began with a good performance of an English song, continuing with Aboriginal ones. Mitchell was very impressed with a poetical kangaroo song. One verse described the weapons used in the hunt, another recounted an unsuccessful chase, a third was inspired by the night, the fourth celebrated the following daybreak, the next was about the chase renewed and, finally, there was the death of the kangaroo. Mitchell so admired this song that he persuaded Primbrubna to repeat the words slowly and, having written them down, he repeated them to the guide. The flatterer was then flattered because Primbrubna told Mitchell: 'Not so stupid fellow you, like other white fellows'. Mitchell then discovered, by looking at the stars with Primbrubna, that Aboriginal astronomy was full of figures of men and animals, the moon having once been a black cockatoo, and so on. The next morning, Mitchell was shown some marks on trees made with tomahawks a year earlier by Aborigines from Lake George which Primbrubna thought hostile. Soon after, to Mitchell's disappointment, Primbrubna left the surveyors to return to his own people.

[Mitchell] Tuesday 17th June ... In the evening the native sung a good English song, and also various native songs, one, the Kangaroo song seemed very poetical, according to his description of it - one verse seemed to be a description of the implements, another the unsuccessful chase, another the night passing, another day break next day - another the chase and naming Worrong Mountain & other mountains; and, finally the death of the Kangaroo. I got him to repeat the words slowly, and then having written them down, I repeated them to him, when he said "Bal (not) stupid fellow you, like other white fellows." When I asked him, however, to explain the meaning of each word, I found that one meant kangaroo, another Emu, another limbs, another liver, heart &c, which amused us a good deal. His astronomy was full of figures of men and kangaroos; the moon was once a black cockatoo &c. In the morning he found some hostile marks on the neighbouring trees, which had been made by the natives of Lake George, on an incursion about a year before. They were cut with tomahawks on different trees as follows. This native left us on pretense of seeing his friends on a plain at Tengobideja and did not return. He was a very intelligent fellow. His native name "Primbrubna."

|

| T.L. Mitchell Field Notes... [extract], 1828-30. Showing scarred trees. |

(Sources: T. L. Mitchell, Field, Note and Sketch Book 1828-30, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, C42, 31 May 1828, 16-17 June 1828. Translation here: http://archival-classic.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2017/D06407/a1484.html. Additional digital files available here: https://www.sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/checklist1826-1830.php).

1829

- 19 January 1829: Various Aborigines in the Argyle district are given blankets, slop suits, or rewards for assistance provided in capturing bushrangers. Sources: Link van Ummersen (1992); Mitchell Library MSS Index, Australian Aborigines - Colonial Secretary to Magistrates Inventory, 29 January 1829 (?1828); 12 February - 1830 Letters from Government Offices pp.28-29.

1830

- Battle of Fairy Meadow, between the Illawarra and Bong Bong tribes (Organ 1990, Bowern 2018). Reminiscences of Martin Lynch, interviewed by Archibald Campbell in 1897 and as recorded in a letter written by Lynch in 1898.

Transcription: Aborigines. Mr Lynch in his early boyhood - about 1830 - witnessed a battle at Fairy Meadow, between the Illawarra blacks and the Bong Bong blacks, over something in the lady line. The battle took place in a naturally clear spot - the real Fairy Meadow - situated immediately on the north and east of what is now the junction of the Main Road and Mt Ousley road. Mr Lynch declares that several hundred men on each side took part in the battle, which consisted of a series of intermittent onslaughts, which extended over three days and nights. During the continuance of the battle some of the men and women would go abroad hunting for food. The battle was won by the Illawarra blacks. Many blacks on both sides were killed and more wounded. The killed were buried in the tea tree scrub between the site of the battle and the sea (between two arms of Fairy Creek). The weapons were mostly spears, "nullah nullahs", and "waddies" of one shape or another. Mr Lynch explained that the dead of both parties were buried along the northwest bank of Fairy Creek, east of the North Illawarra Council Chamber. About 70 men were killed in the battle, including both sides, and all the corpses were buried by the victorious Illawarra tribe. The graves were dug along the bank of the creek, which was somewhat sandy, the depth of each being about three or four feet. The blankets, tomahawks, "billy" cans and all other articles owned by each of the deceased were buried with them, some wood also being placed on top of the corpse. The explanation given by the survivors was that the wood and other articles would be required by the departed "in another country". He (Mr Lynch) witnessed the burial of several of the men killed in the battle. The place of the burial was not the usual locality for interment by the blacks - the slain in battle only being placed there. The usual burial place in that quarter was in the sandy bush land on the south side of Fairy Creek - now Stuart Park - east and west of the Pavilion. The sand banks, near Tom Thumb Lagoon, Bellambi, and Towradgi, were likewise burial places, where many bodies were interred from time to time. He had witnessed nearly twenty blacks buried in the spot near Fairy Creek already mentioned. As a rule they did not desire white people to know where they (the blacks) buried their dead, but after the district became somewhat settled their burials could not be kept secret. The blacks carrying out the burials and the deceased’s relatives used to stripe their bodies and heads and necks and limbs with pipeclay, as marks of mourning for the departed. Regarding the battle, he had witnessed it each of the three days over which it extended - hostilities being suspended at nightfall. His mother and step-father also viewed it each day from the elevated ground between Mr Bate’s brickyard and Mrs Aquila Parsons’s residence. The Illawarra tribe fought on the north side of the Meadow, and the Bong Bong tribe on the south. Spears were thrown thick and fast between the combatants, and repeatedly he had seen men struck with them on both sides, sometimes causing the man struck to fall mortally wounded, while in some instances the wounded person would struggle to withdraw the spear - not always successfully. In close quarters "nullah nullahs" and other hand to hand weapons were used furiously in the mortal combat - one of the persons so injured not infrequently having his skull crushed or limbs broken. The dead were left unburied until the battle was over, after which the victors carried the bodies to the place stated and buried them there as already mentioned. The cause of the battle was the taking away from the Bong Bong blacks a young "jin" of their tribe by an Illawarra black designated "Dr Ellis" by the whites. He induced her to leave her tribe with him, and carried her away captive unknown to them, and hence the rupture between the two tribes, resulting in the battle and bloodshed narrated. The captive maid was in the immediate vicinity of the hostilities all the time as were the "jins", the latter carrying about and supplying to the male warriors the deadly weapons and other requirements of the ongoing engagement. The young jin who was the cause of all the bloodshed did not hide her desire to flee to her own tribe, even while the battle was proceeding, but from doing so she was forcibly prevented, and beaten again and again most brutally, until her head was almost in a state of jelly and was covered in gore - the brutality being inflicted mainly by her captor ("Dr Ellis"). So frightfully was she beaten and battered that his (Mr Lynch’s) mother took compassion on her and took her to her own home and doctored her there for some time until she recovered sufficiently to rejoin her lord and master and his tribe. The Bong Bong blacks came down the mountain range from their own country, making the descent opposite Dapto, to wage war with the Illawarra tribe, at whose hands they sustained defeat in the pitched battle as stated - the survivors returning again by the same route over the mountain to Bong Bong to tell their tales of blood and daring deeds by the way. The young woman, or "jin", concerning whom the battle took place, remained in Illawarra all the remainder of her life and passed away, as did the whole of her race, from time to time in rapid diminution, unknowing and unknown in an historic sense. Sanguin was the mortal tribal conflict that had taken place regarding her, and numerous as were the slain that bled or fell in her interest. Her remains, like those of the sable warriors who died concerning her, were interred in the usual crude grave in Illawarra soil, without a stone or any other sign to show her last resting place. Mr Lynch states that he never remembered the blacks having actually murdered any white persons in the district, though several were scared by them now and again. He mentioned however that Mr Hicks, subsequently of Bulli, was decoyed into the bush in the Shoalhaven district under the plea of showing him some cedar, and that he narrowly escaped being killed by his false guide or guides. He saved his life by jumping over a precipice, falling on suspended vines and thereby being saved from being smashed in the fall.

In a letter written by Martin Lynch in 1898 he states: Recollect to see the fight between the Bong Bong Aboriginal tribe and Wollongong tribe. Both tribes in number wood be fully 15 hundred. 1000 500. The number killed would be over 100. This was originated by Aboriginal Dr Ellis taking a gin away from the Bong Bong tribe. The fight was on Mr James Townsend paddock, which is actually Para Meadow. They buried the dead at the bottom on Townsend paddock on an arm of Fairy Creek.

1831

- Surveyor Robert Hoddle travels through the area, from Bong Bong, past Yarrawa and possibly via Bundanoon down to the Shoalhaven River. Hoddle painted a number of watercolours of the region during the journey, revealing the steepness of the gorges and variations in the terrain. He was assisted by Aboriginal guides.

|

| Robert Hoddle, [View looking north-west towards Bundanoon escarpment, en route to the Shoalhaven and Kiama], watercolour, circa 1830. |

1832

- 40 blankets distributed to Aborigines at Berrima, 1832.

* William Romaine Govett surveys in the area between Bulli, Appin and Bong Bong. Source: Notes and Sketches taken during a surveying expedition in N. South Wales and Blue Mountains roads, Mitchell Library, Sydney.

1833

- 40 blankets distributed to Aborigines at Berrima, 1833.

1834

* Carl von Hugel, Journal of a Visit to New Holland, 1833-34, Mitchell Library, Sydney.

Transcription: Tuesday, 29 July 1834. [At Mullet Creek, Illawarra] we saw a blackfellow of the Bong Bong tribe with a white feather in his hair, a sign that he was acting as a messenger to the Illawarra tribe. These messengers are received in a singular fashion: the band to which the messenger has come sits on the ground and he sits down in front of them and then follows a long silence, during which they look at each other. Then there is an exchange, one word at a time, until the reason for the mission, usually war or peace, comes up for discussion. We arranged for the man to come into our camp in order to show us the way to Bong Bong the next day, which he promised to do (Organ 1990, Bowern 2018).

- 40 blankets distributed to Aborigines at Bong Bong, 1834.

1836

- Blanket distribution at Berrima. Refer transcriptions: Organ (1990 211-2) and Bowern (2018 71-2).

- 4 October: Quakers Backhouse & Walker travel from Kangaroo Ground to Throsby Park near Bong Bong. They are guided by a local man (Backhouse, 1843, 435-6; Organ 1990.)

- 12-18 October: Backhouse & Walker travel from Marulan north to Throsby Park and Bargo, visiting Oldbury (Sutton Forest) and Mittagong. At Bargo they mentioned the following:

We met several companies of blacks. Some of the women had considerable quantities of Native Currants, and fruit of Leptomeria acida, that they were carrying in vessels scooped out of the knots of the gum-tree, some of which will hold several quarts. (Backhouse, 1843, 445-6.)

1837

- Blanket distribution at Berrima, 1837.

- Captain Robert Marsh Westmacott, former Aid-de-camp to Governor Richard Bourke, settles at Bulli in 1837. Over the next decade he sketches a number of landscape views and of Aborigines in the Illawarra and nearby regions, some of which are later lithographed. One of these is: Mountain Pass from Jamberoo to Bong Bong (original sketch and later lithograph, published in London, 1848). Westmacott noted in regard to the image: The Pass is very precipitous, and used only by the natives, who appear upon all occasions to make their paths pass over the summits of eminences, instead of making an easier ascent by going round them. (Westmacott, 1848).

|

| R.M. Westmacott, Mountain Pass from Jamberoo to Bong Bong, Illawarra, N.S.W. |

1838

- Blanket distribution at Berrima, 1838.

* Alexander Berry, Recollections of the Aborigines, May 1828, manuscript, Mitchell Library, Sydney. (Organ 1990). Refers to links between the Shoalhaven Aborigines and the Bong Bong tribe.

1839

- Whilst the Bundanoon area may have been occupied illegally by squatters from around the late 1820s and through the early 1830s, it appears that it was not until 1839 that the first official leases were granted by government. For example: Yearly Leases of Land Auction - #168 – Argyle, 800 acres at Bundanoon, at the confluence of the Bundanoon Creek with the Shoalhaven River; #169 – Argyle, 640 acres; #170 – St. Vincent, 700 acres (Sydney Gazette, 9 January 1839).

- Blanket distribution at Berrima, 1839.

* [King Charles] Yass, Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 13 February 1839, 2 (Bowern 2018).

- Lady Jane Franklin, wife of Tasmanian governor Sir John Franklin, visited the Illawarra and recorded the following on 14 May 1839: .... crossed the forced and natural channel of Mullet Creek and found about half a dozen men with soldiers with pistols in hand standing over, hoisting up piles to sink in bed of river. Near here we saw some natives from Bong Bong and a Lascar of China who said he kept to them because they were of his own colour. One woman would not come forward when desired of her husband and he said she was shy .... (Organ 1990).

1840

- For sale, 640 acres south of Colyersleigh 3 miles from Sutton Forest …. There is a never failing creek running through the estate, known as Colyers Creek…. This creek falls into the Bundanoon, or Throsby’s Creek. (Sydney Gazette, 6 June 1840). Such isolated land sales continued through the 1840s and 1850s.

- Return of Aboriginal Natives at Berrima, 1 September 1840, Archives Office on New South Wales, 4/2479.1, 40/842. See transcriptions: Organ (1990 265-7) and Bowern (2018 73-4).

* Two Aboriginal men - Blucher and Charley - die shortly after their release from Berrima goal, Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 7 September 1840, 2.

Transcription: To The Editor of the Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser. Sir,- In the abstract of the proceedings of the Court of Quarter Sessions held at Berrima last month, which appeared in the Monitor of yesterday, it appears that two aboriginal natives, Blucher and Charley, who had been charged with murder, were acquitted and discharged. A note is appended stating that "they were turned out of gaol in a most deplorable state, naked and half (if not whole) starved, which together with bodily ailments made worse by long confinement and indifferent usage, and without medical assistance they both died shortly after they were liberated; a scandalous affair." Now when these two poor men were received into Sydney Gaol, namely, on the 20th of last March, the only clothing they had on them was each a single dirty blanket. When they left Sydney Gaol on the 11th July ult, they had each a comfortable suit of warm woollen slop clothing, and a blanket. Their bodily ailments while in Sydney Gaol were regularly and anxiously attended to, and they had constant medical assistance, and humane, and I have no doubt judicious treatment. They were well fed - indeed much better than the white men confined; in as much, as their rations were served to them separate from their fellow prisoners of a different colour,and more abundantly. How they have fared since they left Sydney, I have no means of ascertaining. As to the length of their confinement, it was caused by the difficulty, indeed the impossibility of procuring an interpreter capable of communicating between them and the court. Your insertion of these few remarks, will oblige. A Constant Reader.

1841

- Blanket distribution at Berrima, 1841.

* Charlotte Waring Atkinson Barton, A Mother's Offering to Her Children, Gazette Office, Sydney, 1841. The Barton family were resident at the property Oldbury, Sutton Forest, built by Charlotte's first husband James Atkinson. A chapter on Anecdotes of the Aborigines of New South Wales (pp.197-214) includes reference to Sutton Forest and Shoalhaven Aborigines. Refer also Louisa Atkinson (1853), daughter of Charlotte Barton. Charlotte also did a numbers of artworks of the area, including portraits of local Aborigines.

Anecdotes of the Aborigines of New South Wales

Mrs. S. — Little Sally the black child has been accidentally killed.

Clara. — Oh! Mamma, do you know how?

Mrs. S. — She was playing in the barn, which is only a temporary one; and pulled down a heavy prop of wood upon herself. It fell on her temple; and killed her immediately.

Emma. — Do you not think her mother will be very sorry, when she hears of it?

Mrs. S. — Alas! my dear children, her mother also met with an untimely death. These poor uncivilized people, most frequently meet with some deplorable end through giving way to unrestrained passions.

Julius. — Oh! do tell us all you know about little Sally and her mother; if you please, Mamma? It will make the evening pass so pleasantly; and I will be drawing plenty of animals, to fill the little managerie I am making.

Lucy (kissing her Mamma). — Do tell us dear Mamma? My sisters are going to work; and may I set your work-box in order; and then we shall all be so happy.

Mrs. S. warmly returned the fond embrace of her little Lucy; and after they were all seated, began the following narrative: —

HISTORY OF NANNY AND HER CHILDREN.

The mother of the poor little black girl, who has lately met with so dreadful a death, was called Nanny. I do not know her native name. She was a remarkably fine, well-formed young woman. Surely Clara and Emma you must remember Nanny coming occasionally, with other blacks? The last time I saw her she had this same little Sally with her; who could just then run alone.

Clara. — Oh yes, Mamma! it was a pretty, fat, little brown girl, quite naked.

Emma. — And I remember we asked you to give her a little frock: but before you could get one they were gone.

Mrs. S. — That was the last time I saw the mother. The child was a half-cast, or brown child, as you call them; and soon after the time you speak of, Jane D.......n, a young married woman, who had lost her only child sometime before, took a fancy to little Sally. And her mother agreed to leave the child; as soon as it was weaned. You know the black children are not weaned so soon as white children: most probably from the uncertainty and difficulty in procuring proper food. Though I have remarked that the babies will eat voraciously, at an age when a tender white babe would not touch such food.

Clara. — Mamma, I am sure some of the black children are more than four years old, when they are weaned.

Mrs. S. — They are my love. But we will continue our narrative. When little Sally was about two years old, she was weaned; and taken to her future home. It was evening when the child was left; and she was naturally much distressed, when she found herself deserted by her mother. Jane was soon after, going to put her to bed: but she was greatly alarmed at the idea of being put into a bed; and said with much eagerness, “Bail nangarrie waddie” (not sleep in a bed) pointing to the bed. Nangarrie like-a-that,” (sleep like that,) curling her little body round on the ground floor of the hut. To please her, Jane spread a blanket for her on the floor; and poor little sorrowing Sally covered it about her. Several times during the night, Jane and her husband heard the poor little girl moaning; as if she were lying lamenting her deserted state. The man, as was usual, opened the door of the hut very early; and little Sally went and stood outside; looking in all directions; and uttering the most piercing coo-ee-es imaginable. Jane assured me, that she was astonished that such a baby could utter such loud and piercing sounds. The forest echoed and rang with them; and Jane who is a kind-hearted young woman, felt her heart thrill with pity and fear.

Lucy. — Oh! Mamma that is just what I should do, if I lost you: cry as loud as ever I could; and be so very, very sorry! What did they do for the poor little girl?

Mrs. S. — They tried to console her; for she was very much distressed, when she found her mother did not reply to her coo-ee-es. She would frequently wander about; and call in this wild way; so peculiar to the aborigines: but her mother was far away. At length time in some degree reconciled poor little Sally to her new parents and altered state of life: when the tribe came again; and with them her mother. The child immediately recognised her; and you my dear children, can judge, better than I can describe, the joy she felt at again seeing her. The poor little babe rushed into its mother's arms; but the unnatural mother sent her child from her. Poor little Sally screamed and was refractory; when her mother whipt her severely, and left her.

Emma. — Oh! Mamma, this is too shocking! to leave her little child among strangers; and then whip it for being so glad to see her again; and for wishing to go with her. Ah! Mamma, I am very sorry for the poor little thing. I wish you had taken it from such a bad mother; and then we would have done all we could to have made it forget, it ever had such a naughty, cruel mother. Why did she go near, to teaze her poor little girl?

Mrs. S. — I quite agree with you Emma, that she was very blamable to go near the place; to unsettle her child; but she was not in many respects a bad mother; as I will tell you more about soon. Jane treated her adopted child very kindly, and tenderly; dressed it well; and kept it very clean. I saw it when it was about four years old; and it was an interesting child; with large black eyes, black curling hair, a pleasant laughing countenance, fat, and had all the appearance of being happy. Perhaps her mother considered that she was better situated with Jane, than she could be wandering about the forests, in search of precarious food. You know at the best, the women and children are badly off.

Clara. — Notwithstanding, Mamma, it seems unnatural for a mother to part with her child. Though I know there is a little boy, who his parents wish you to take: but I think if I were ever so poor, I would not part with my children. Did Nanny ever go again, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — More than once, my dear: when the same scenes took place: affection and tears on the part of the child; and severity on that of the mother. One time when the blacks were encamped in the neighbourhood of Mrs. D.......n's hut, they heard a dreadful screaming in the night; and the husband arose and opened the door: he could not see any thing; and concluded the blacks had been drinking; and were fighting. Not wishing to interfere with them, while in that state; he closed the door; and the noise soon ceased: but in the morning they found poor Nanny had been murdered! It appeared a black man named Woombi (Nanny's half-brother) had been quarrelling with her, and was beating her: she fled for protection near the hut; when he threw a spear after her; which entered the back of her neck; she continued to run, with the spear in her neck: but was soon overtaken by the furious Woombi; who struck her on the head with his tomahawk; and soon dispatched her. I was told she was a dreadful sight in the morning!

Clara. — Poor thing! what became of her?

Mrs. S. — The blacks dug a grave near the spot; and buried her in a sitting posture: putting her tomahawk, pannikin, net, bangalee, and indeed, all her little possessions, with her in the grave. Lucy. — How strange to bury all her things!

Mrs. S. — It is their custom, and they appear much shocked at the idea of the clothes, &c., of a deceased person being kept, after their interment. The tribe belonging to the neighbourhood where our property is situated, were very much attached to your dear lamented father. You know they never mention the name of a deceased person; but they were giving me to understand, the regret and sympathy they felt at his loss. I had the locket with me at the time, which has a lock of all our hair in it. I showed this to them, pointing out his (to us) much valued brown curl; when they uttered a piercing cry; and all turned away; holding down their heads a short time: when they looked up I saw they were in tears. One of the women stepped aside; and whispered to me “Bail you show that to blacks ebber any more missus.” This of course I promised to refrain from. I was much surprised and effected at their manner; having wished to give them pleasure. It was six years after our bereavement. In a savage state they bury the living infant with its deceased mother: sometimes when several months old! Emma. — How terrible! Mrs. S. — Yes. They place the living child in the grave, by the side of its dead mother; and after covering it with earth, lay heavy stones upon it!

Clara. — Poor little creatures, how cruel! Do you think it is ever done now Mamma?

Mrs. S. — No doubt it is, far in the interior; where their ancient customs are still kept up. The poor babies, appear to be thought very little about.

Clara. — You know Jenny has left three infants to perish in the bush; because, she said, it was too much trouble to rear them: and when our cook asked her if native dogs had eaten them, she replied, “I believe.” And I am almost sure she killed that little black baby girl, she had sometime ago; for it suddenly disappeared; and when we questioned her about it, she hung down her head and looked very foolish; and at last said, “Tumble down,” It was buried in one of our paddocks; and some stones laid over the grave: when we were taking a walk, with our nurse, we met one of our men, who opened the grave; and it was evident the body had been burned; for there were remains of burnt bones, ashes, and hair.

Emma. — Billy the black man killed one of his little babies.

Mrs. S. — Yes, he took it by its feet and dashed its brains out against a tree. Some however, are very kind parents: but I do not think they are in general, to their infants. I remember a tall woman, quite a stranger, coming with a black infant, of less than a month old. It was so ugly and covered with long hair, as not to look like any thing human: but worse than all, the poor little creature had been terribly burned, by the mother putting it too near the fire; and falling asleep. From the ankle to the hip, on one side, it was nearly burned to the bone. It had been done some days; and the fire seemed out. I therefore had it dressed with lard spread on rags: soon after, I heard the bandages were off. The negligent mother had left it; and one of their hungry dogs, attracted by the smell of the lard, had torn off the rags; and dragged them away; notwithstanding they had been tied on carefully. They were replaced; but the cruel mother appeared quite indifferent to the sufferings of her tender babe. About a week after, I understood it was dead: probably made away with.

Emma. — What tribe did she belong to, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — I do not recollect: there were a great many tribes collecting; to the number of perhaps 200 blacks on our estate: they were assembling to fight; and we found it a great nuisance. Bullocks and horses are very much frightened at them; and the men found it almost impossible to continue their ploughing.

Emma. — It is very odd, that animals should know the difference between black and white people.

Mrs. S. — I do not suppose that it is their color altogether. It may be the unpleasant smell which they have; from want of cleanliness; and constantly rubbing themselves with the fat of the animals which they kill.

Julius. — Did they fight, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — Yes; but their battle will furnish a subject for another evening: we will return to poor Nanny.

Emma. — Do you think the women were sorry for poor Nanny, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — Yes; I think they are kind to each other. The son of a cottager residing at Wingelo, saw the ground had been lately dug up in the bush, not far from where they lived: curiosity led him to examine into the cause: when he found the body of a little black infant: he ran home with it, saying, “Look, mother, I have found a little black baby.” His mother made him take it back instantly; and bury it, as it was before. She then went to look for its mother; she soon found her, sitting with her chin resting between her knees; crouching before a fire: another woman sat near her; who was (according to their ideas on the subject) endeavouring to draw away the pain her friend felt. This was done, by laying a string across the body of the sick woman, where the pain was most violent; the other end was held by her friend; who kept drawing it across her lips, till they were sadly cut; and bled very profusely: while she was doing this, she kept up a mournful monotonous chant. The cottager left her to prepare some tea; she returned with it in about a quarter of an hour; when she found the woman was dead; and several black women were preparing her body for interment. They tied her knees to her chest; and her arms to her sides; by passing strips of stringy bark round her. A hole was then dug; and she was put into it; and her dead baby by her side.

Clara. — Poor woman! how very soon they buried her. Did they carve the trees about?

Mrs. S. — I do not know: but I think the blacks in the civilised parts of the country, are too indolent now to take so much trouble. The grave on the side of our hill, must have been made at least 23 years ago; and yet the carving in many of the trees is quite visible: though we can only from that circumstance, conjecture where the grave was.

Lucy. — Did poor little Sally know her Mother was killed, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — I do not think she did my love. I believe it happened about a year after Mrs. D. had adopted her.

Emma. — It was very unnatural for her brother to kill her, Mamma: what do you think they quarrelled about?

Mrs. S. — The blacks have a great objection to their women living among white people. Nanny was particularly fond of this; and it made the blacks angry. Indeed Nanny would have married an overseer to a Mrs. J. several years ago. The man was very anxious to marry her: but Governor Darling would not allow it. At this time she had a little brown boy, whom she called George. He was a fine little boy; some months older than you, Clara. One day she brought him for me to look at. I admired him very much; and gave her a few clothes for him. Clara was in long petticoats. Nanny asked me to let her see “piccaninnie's” head: accordingly the cap was put back and the little golden locks exhibited. Nanny was in exstacies; she clapped her hands and exclaimed “All same Georgey Missus.”

Emma. — How droll. I dare say the babies heads were not at all alike: most likely Clara looked like a wax doll beside Georgey.

Julius. — What became of him, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — When he was about three or four years old, Nanny came one day without him; and told me Mrs. J. had sent for him to Sydney, to put him to school: he remained there some time. Afterwards, I heard he was acting as a little shepherd at Bombarlowah; over a flock of sheep belonging to the person his mother would have married. I believe he still lives with the same person; and I heard he had given George some sheep and cattle of his own. Nanny was very fond and proud of her little George, before he went to school she used to wash him and comb his hair; which was light and curly.

Julius. Where did she get a comb from, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — She used to carry a broken comb, which had probably been used to comb a horse's mane.

Clara. — Not a very fine one then: but better than none; and shewed she wished to keep her little boy clean.

Mrs. S. — One day when the tribe was encamped near the house; and Nanny and her child nearer than any of the rest: I went into the store at the back of the house, with the cook and your nurse. Suddenly little George gave a piercing shriek. I sent the nurse to see what had happened; and found Nanny had bitten the child severely on the back of his arm. She looked very much ashamed, when we reproved her for it; and said, piccaninnie wanted to suck.

Lucy. — Mamma, that is just what pussy does, when she wishes to wean her kittens.

Mrs. S. — It reminded me of a cat Lucy; and I felt quite disgusted with Nanny: but upon the whole her children bore evident signs of her affection and care.

Clara. — How curious it is that the black children do not change their teeth, Mamma.

Mrs. S. — It is very remarkable. I have taken a great deal of pains to question both parents and children; and they all have told me that they do not. This may account for the large size of their babies' teeth: which we have thought so extraordinary. Some of the half caste children change their teeth; others do not.

Emma. — Jane must have been sadly distressed at poor little Sally's death; she was so much attached to her.

Mrs. S. — She was, my dear. She told me she would never take another child. Sally for some time had given her a good deal of trouble and additional work: but for the last few years her love for the child, who was very docile and affectionate, had quite overbalanced any trouble she might have had with her; and she found her a great comfort. I suppose the child was about six years old when the accident happened. Jane was from home; and her husband ran immediately for Dr. A., who told me the man was as much distressed, as if it had been his own child.

Emma. — Where was it buried, Mamma?

Mrs. S. — They opened poor Nanny's grave, and placed her by her mother.

Clara. — If the blacks had been about, they would have been very much terrified at this: you know they are fearful of even going near any place, where any one has been buried.

Mrs. S. — Yes, we had an instance of that, when Dr. F. wanted one of the blacks to dig up the bones of a black; who had been interred on our land many years before. The black man looked dreadfully shocked; and exclaimed “Too much gerun me:” (meaning frightened) “jump up white fellow long time ago.” You know they think the white people have once been black.

Clara. — Yes; I have heard of two people, whom they think they recognise as their departed black friends; and call them by their names, when speaking of them.

Emma. — How odd: perhaps they think white people have once been black, because they see those who die look pale.

Mrs. S. — It would be difficult to ascertain what gave rise to such an idea.

Julius. — I wonder Sally was not buried in the Church Yard.

Mrs. S. — She was not a Christian, my dear. Jane had neglected to have her christened; though she told me she had intended it. Another melancholy instance of rocrastination. Oh! my children! how very, very fatal is this habit of putting off from day to day, what should be done immediately; for we know not the day, nor the hour, when time may cease for us; and we be summoned into eternity Let us dear children, endeavour to profit by the frequent warnings we have, of the uncertainty of life. “For here we have no abiding place,” but, “In the midst of life we are in death.” May we be found watching! and may God in his mercy so renew a right spirit within us, through Jesus Christ, that in our anxiety to acquire temporal knowledge, we may not forget that “one thing is needful,” and so pass through this life that we gain a knowledge of the things which belong to our peace; and become at last heirs of immortality!

“Then when the last, the closing hour draws nigh,

And earth recedes before our swimming eye;

When trembling on the doubtful verge of fate,

We stand and stretch our view to either state,

Teach us to quit this transitory scene,

With decent triumph and a look serene;

Teach us to fix our ardent hopes on high,

And having lived to God, in Him to die.

------------

1842

- Blanket distribution at Berrima, 1842.

* Isaac Nathan, Koorinda Braia [Aboriginal song], Sydney, 1842. Sung by Aborigines at a feast in Berrima during 1845.

1843

* James Backhouse, A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, Hamilton, Adams and Co., London, 1843, 560 + cxliv.

1845

* Country News: Berrima, The Australian, 31 May 1845. Report on blanket distribution.