Mount Gingenbullen burial mound - Aboriginal significance

Shoalhaven & South Coast: Aborigines / Indigenous / First Nations archive | Amootoo | Aunty Julie Freeman art | Berry's Frankenstein & Arawarra | Blanket lists | Bundle & Timelong | Byamunga's (Devil's) Hands | Cornelius O'Brien & Kangaroo Valley | Cullunghutti - Sacred Mountain | Death ... Arawarra, Berry & Shelley | God | Gooloo Creek, Conjola | Indigenous words | Kangaroo Valley | Mary Reiby & Berry | Mickey of Ulladulla | Minamurra River massacre 1818 | Mount Gigenbullen | Neddy Noora breastplate | Timelong | Ulladulla Mission | Yams |

|

| Mount Gingenbullen burial mound, looking east-northeast from Oldbury Road, 31 January 2023. |

Abstract:

Mount Gingenbullen, Sutton Forest, New South Wales, Australia, is the

site of possibly the largest Aboriginal burial mound in the country,

dating from circa 1816-1818. The author presents a detailed history of the site and calls for its study, protection, preservation and recognition as a site of immense cultural heritage significance to the Dharawal / Wodi Wodi, Jerrinja and Gundungurra communities.

-------------------

---------------------

gʊn : gʊn : bulʊ : ŋ

gayan : gayan : bulay : ng [gingenbullen]

very : very: sick (dead) place

dulʊ : ɲa(ra) : m(ulu) : bulʊ

dulaia : na : m : bulay [tillynambulla]

bent : knotted : deflated : down / corpse, graveyard

-----------------

Contents

- Uncle Gordon's story

- Origins

- Location

- What do we know?

- The Atkinson reports

- Another burial mound

- Possible origins

- 1816 - Cannabygle's Tribe & the Appin Massacre

---------------------

1. Uncle Gordon's story

The following reminiscences regarding Uncle Gordon Wellington (1916-2000) were compiled by Chris Illert (c.1950-2024) and published as 'The Last Shoalhaven Lore Master - Gordon Mitchell Wellington' in the Shoalhaven Chronograph, August 2000:

Prior to his death in 2000 at the age of 84, Shoalhaven Aboriginal elder Uncle Gordon Mitchell Wellington (b.1916) undertook an annual pilgrimage to Sutton Forest near Moss Vale, on the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, for a ceremony held on the side of Mount Gingenbullen at a large burial mound and graveyard. He had been doing this since the 1930s and 1940s, following initiation into Aboriginal lore by his elders. The scars on Uncle Gordon's body attested to this. At that time the ceremony was attended by twenty or more local people, descendants of the original tribes and clans of the area including the Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven. By the 1980s the numbers had whittled down to just two - Uncle Gordon, and a old friend from Sutton Forest who was descended from one of the men who threw a spear at the Battle of Fairy Meadow back in 1830, held between the Illawarra people and the Bong Bong tribe. So it was that, during the 1990s, the elderly Uncle Gordon Wellington would leave the Illawarra Highway and turn up Oldbury Road, towards the Hume Highway, passing along the northern edge of Mount Gingenbullen. As the road suddenly veered south-westerly with a kink, and went from tar to dirt, he would shorten his steps, round a corner, and head down a slight incline towards the entrance gates to Oldbury House. By the road just before the gates he would look at the old post and rail fence, get to the other side anyway he could, and approach a large mound of earth. There he would repeat a ceremony he had engaged in for decades: he would do a special dance and sing a song; place flowers - white waratahs - on the mound in memory of an ancestor buried there during the early years of European settlement; and sit down and commune with the spirits. 'They are fighting. They have unfinished business here', he said when interviewed about the site shortly before his death. 'They are fighting the white settlers who have desecrated their burials, their graveyard.' Uncle Gordon spoke of a massacre .... One day he turned up and noticed that landscaping work was being undertaken in the area of the burial mound and surrounding graves. He approached the owner of the property and expressed his concerns, briefly outlining the significance of the site. 'There are no burials here', was the sole response he received. The work continued.... Uncle Gordon passed away in February 2000. He was the last known knowledge holder of this sacred ceremony of remembrance, and engagement with spirits from the past..... (Illert 2000).

-----------------

2. Origins

We do not know where the remains of the Aboriginal victims of the frontier massacres in New South Wales lie. We do not even have more than a rough idea of where most of the actual massacre sites are. (Byrne 1998)

The Mount Gingenbullen Aboriginal burial mound, originally described in 1853 as 100 feet long and 50 feet high, appears to be the largest such burial mound in Australia, on par with the barrows of England. Yet despite this, it is little known. Some consider it a myth; others, that it has been bulldozed and utterly destroyed; yet many know of it as real and surviving. The present article aims to clarify what is known, what is rumoured, and what misinformation currently exists in regard to this sacred site.

The mound dates to the immediate years prior to 1818. It was initially described by members of the Atkinson family of Oldbury, Sutton Forest, during the period 1841-63, based on information directly received from knowledge holders within the Indigenous community, beginning in 1821 when James Atkinson received his initial grant. In more recent times it has been cited as 'the earliest identified Australian Aboriginal massacre burial site' by Dr. Chris Illert (pers. comm 17 November 2022). The reasons behind this claim are briefly presented in his article Blue Mountains Dreaming (Illert 2003) and more substantially within the Report on Wongonbra proposed 400ha subdivision application (Illert 2007). Illert claims that numerous Aboriginal people were given sugar laced with poison by original land grantee James Atkinson (1795-1834). There is no substantive evidence for this. Nevertheless, questions regarding the site arise, such as:

- What exactly is this archaeological site;

- Where is it located;

- What is its cultural significance;

- Was it constructed by First Nations peoples, or Europeans, or both;

- What is its present status in regard to research, preservation and protection; and

- If the site is indeed associated with a massacre, or mass killing, as seems likely due to its unprecedented size, then what event was that associated with, and when did it occur?

This article will attempt to provide answers to these questions. Unfortunately, whilst much is known, only some can be addressed with any degree of certainty, and others are dependent upon further investigation. The cultural sensitivity of the site must also be considered in any discussion of its history, content and efforts to protect and preserve it.

|

| Extract from article by Dr. Chris Illert, 2007. |

----------------------

3. Location

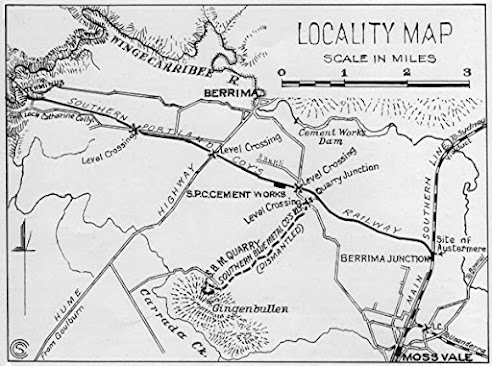

Mount Gingenbullen (coordinates -34.537473 S 150.318863 E) is a geographical feature located in the Southern Highlands of New South Wales, Australia, just to the west of the town of Moss Vale and north of Sutton Forest. It is a prominent feature on the landscape, comprising an approximately 3 kilometre long, northwest - southeast trending ridge within the Great Dividing Range, composed of volcanic rock designated Gingenbullen dolerite dated to the Jurassic geological period (Robertson 1962). The feature comprises two levels, with a peak 802 metres (2,628 feet) above sea level and prominence 127 metres (417 feet) above the surrounding plain. The south-eastern lower terrace is around the 650 metre contour. The area is bounded on the northwest by the Hume Highway; on the north and east by Oldbury Road; on the west by Golden Vale Road; and on the south by the Illawarra Highway, as shown in the maps below.

|

| Oldbury Road (blue) with burial mound (red) and Oldbury House (green). |

The approximate site of the burial mound (identified, but not as yet archaeologically confirmed) is on the far north-eastern corner of Mount Gingenbullen, at the lower 650 metres contour level and slightly to the north of the Oldbury homestead. The latter comprises a number of buildings dating back to Australia's colonial period, with the Georgian Oldbury House constructed between 1826-1830 (Newby 2017).

The burial mound is located by the side of the unsealed Oldbury Road and close to Oldbury House, on a slightly terraced (flat) area currently utilised as a landscaped, garden orchard. Both the burial mound and Oldbury House location are indicated on the map above in red and green respectively. Nearby is a natural spring which feeds a creek - commonly called Medway Rivulet - running along the western edge of Mount Gingenbullen and close to the house. Oldbury Creek, which crosses the Hume Highway, is located approximately 2 km north of the mound and Mount Gingenbullen. Oldbury Road skirts the area of the mound in a semi-circular kink (refer aerial photograph below, with road marked in blue and burial mound in red outline).

The mound has been subject to landscaping in recent years (since the 1990s?), with concrete and brick tiers on the western edge, a circular fountain(?) structure on the top, and tree plantings all around as of January 2023. This can be seen from the Google Maps image above, with the approximate outline of the mound indicated in red therein and the Oldbury Road kink in blue. Verification that this is the precise location of the burial mound described in detail below has yet to be confirmed by archaeological investigation and consultation with local knowledge holders.

It is likely that the surrounding area is an Aboriginal burial ground. The early designation of the site by local people was Tillynambulla, or Tillynanbullan, which it is suggested refers to a graveyard or place where corpses are buried. Uncle Gordon Wellington made reference to the fact that burials were present beyond the bounds of the mound. There is also reference (refer below under 1994) to a smaller burial mound, now destroyed, and located further to the west and higher up on Mount Gingenbullen.

As noted above, the precise location of the Gingenbullen burial mound is close to Oldbury House. From the details provided by Charlotte (Atkinson) Barton in 1841, Louisa Atkinson in 1853 and 1863, and the recent testimony of Dr. Illert, the mound could be seen from Oldbury Road. It is of concern that the precise position is not, as far as this author is aware, known and listed with the official New South Wales Department of Heritage and Environment database / register of Aboriginal sites, though it is apparently recognised by contemporary Indigenous communities and a listing may be restricted in order to protect the site. The publically available heritage database broadly lists 42 Aboriginal artefact sites in the region. Mount Gingenbullen is not included.

|

| Aboriginal sites and objects (select), Sutton Forest area, AHIMS, 22 November 2022. |

It is hoped that the burial mound is known and listed by authorities. Access may be restricted in order to protect it from possible vandalism. If, in fact, the site is not known and protected, then the fear is ever present that it has been, or in the near future will be, inadvertently or wilfully wholly or partially destroyed and/or desecrated. It is therefore hoped that this can be clarified and the information contained within this article can be of assistance in the process of precisely identifying the location of the mound and ensuring its study, protection and preservation, due to its immense cultural heritage significance.

---------------

4. What do we know?

Mount Gingenbullen was initially referred to and climbed, though not named, by European explorers in 1798, just a decade after the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney in 1788 (Cambage 1919). During the encounter there between the convict explorers and local Aboriginal people, a young girl was abducted and subsequently returned to the tribe. No detailed physical description of the location was given at the time.

Gingenbullen became part of the Oldbury estate in 1821 when the land was granted by Governor Macquarie to recent arrival James Atkinson. What is publically known of the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound comes from colonial-period accounts by such non-Indigenous settlers in the area, based on limited discussions with, and revelations by, the local Aboriginal people. The names of the informants are not known, though they likely date from the early 1820s when the area was first settled. Judging from the writings of Charlotte Atkinson, wife of James Atkinson, there was frequent contact with the local people during the 1820s and the 1830s.

By the end of 1822 the Atkinson estate had been expanded to cover 2,000 acres, taking in the whole of Mount Gingenbullen and surrounding agricultural and pastoral land to the west, north and east (Morris 2017). A poster from the auction sale and subdivision of the Oldbury Estate in 1887 reveals its extent, with the mountain substantially comprising lots 29-47, and therein bounded by Rivulet Creek and Oldbury Road.

|

| Oldbury Estate, Sutton Forest, 1887, auction sale poster. Source: National Library of Australia. |

An extract from the poster shows the location of Oldbury House and Oldbury Road at that time. A contemporaneous white arrow-shaped mark barely visible on the poster points to the approximate location of the burial mound, due north of the house and between it and the road which skirts around it. Obviously the road was specifically formed to skirt around the burial mound, rather than cut straight through it. A stone cottage is situated down slope from it and Oldbury Road.

|

| Oldbury House and Oldbury Road, 1887 [poster extract]. |

Two Aboriginal names for the area were recorded during the early years of European settlement, namely Gingenbullen and Tillynambulla. Gingenbullen and its immediate surrounds since then, and currently, comprises a mixture of farmland, residences, roads, creeks and bush. A number of creeks are associated with Gingenbullen, variously and historically referred to as Whites Creek, Carrada Creek, or Medway Rivulet (all to the west and south) and Oldbury Creek (on the north and east).

Historian James Jervis gave "water running around a hill" as the meaning of the Aboriginal word Gingenbullen (Jervis 1973). However, according to the recent Proto-Australian Aboriginal language research of Dr. Chris Illert, the word refers to a 'very very sick / dead place', which can also be interpreted as referring to a large burial site, or a place where many bodies have been laid to rest (Illert 2021). Illert's deconstruction of the word Gingenbullen can be seen at the head of this article. Likewise, the deconstruction of the word Tillynambulla similarly refers to a corpse or graveyard.

An earlier recording of the word Gingenbullen prior to 1834 has not been identified, and the Atkinson family references are not as yet dated. It was probably noted during the first surveys of the area and the grant to Atkinson around 1821. The same applies to the identification of Tillynambulla, which is referred to in a 1914 Parish Map (Forsyth & Murrell 2020). The New South Wales Directory of 1834 records a journey by a party through the district along the Old South Road in which they:

...went across the Wingecarribee, near Berrima, to the summit of a hill known as Gingenbullen west of Moss Vale.

The photograph at the head of this article shows the burial mound. It was taken on 31 January 2023 and identified based on information provided by Dr. Illert, who visited the site back in 2007 with some local Indigenous knowledge holders. He had previously been informed of the site whilst interviewing Uncle Gordon Wellington during the 1990s. Amie Hunter, a local school teacher of Bundanoon, re-identified the site in January 2023 based on directions provided by Dr. Illert. The photograph above reveals the recent landscaping, along with the large scale of the mound. Its present state is not precisely as described during the nineteenth century. It would appear that natural erosion has taken place over the years, alongside the effects of farming, grazing and recent landscaping.

---------------------

5. The Atkinson reports

The following is a chronology of what we know of the burial mound based on material published by the Atkinson family.

1841

The earliest description of the Gingenbullen burial mound comes from a book published in Sydney during 1841 by Charlotte (Atkinson) Barton (1796-1867). She was the wife of James Atkinson of Oldbury who died in 1834. Subsequent to March 1836, Charlotte was the wife of George Barton. Her book was issued anonymously under the title A Mother’s Offerings to Her Children. By a Lady Long Resident in New South Wales (Barton 1841 [1979]), and therein contained the following brief reference to the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound and associated scarred trees:

The grave on the side of our hill must have been made at least 23 years ago [i.e. prior to 1818], and yet the carving in many trees is quite visible. (Barton 1841, 208-9)

In an extended discussion on death and burial practices, she also noted that the local Aborigines were:

....fearful of going near any place where anyone was buried .... We had an instance of that, when Dr. F. wanted one of the blacks to dig up the bones of a black who had been interred on our land many years before. The black man looked dreadfully shocked and exclaimed, "Too much garun me" (meaning frightened) "jump up white fellow long ago." You know they think the white people have once been black. (212-3)

This quote highlights the Aboriginal belief in reincarnation and the reality of the spirit realm. A Mother's Offering.... is the earliest published reference to the Gingenbullen burial mound, with Charlotte Atkinson referring to it as a grave. The 'carved trees' mentioned by her are known as dendroglyphs and were prominent in New South Wales, associated with burial sites (Etheridge 1918).

|

| Carved tree similar to the type present at Mount Gingenbullen in 1853. |

The shapes and symbols carved in the trunks of living trees are indicative of ceremonial or place markings, as with non-Indigenous burials. One of Charlotte's descendants, Belinda Murrell, has noted that: The carving of the trees symbolised that persons of importance were buried there (Forsyth & Murrell 2020). It has been reported that the marking on the trees often replicated the body markings of the individuals buried nearby. Similar to engraved tombstones, the dendroglyphs are, in fact, an early form of written language, or pictographs. Atkinson's comments would also suggest that the tree carvings were relatively fresh.

1853

On 26 November 1853 an article authored by Louisa Atkinson (1835-72), daughter of Charlotte and James Atkinson, appeared in the Illustrated Sydney News. It described the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound in some detail. At the time Oldbury House was the residence of Charlotte (Atkinson) Barton, whilst Louisa had moved to the lower Blue Mountains with her husband. The article was accompanied by a woodcut line drawing of the mound and nearby carved trees. A copy as printed is reproduced below, along with one in reverse.

|

| Louisa Atkinson, View of Gingenbullen burial mound and scarred trees, engraving, 26 November 1853. |

|

| Reverse image of the engraving, to allow for likely reversed printing effect. |

The original drawing was done by Louisa Atkinson, or her mother Charlotte, both being amateur natural history and landscape artists, with a large body of their work to be found in the State Library of New South Wales collection. Within the print can be seen the prominent, very large, barrow-like burial mound and at least five scarred trees. Some trees are also located within the burial mound edge, pointing to its recent construction. This arrangement - mound surrounded by carved trees - is typical of such Aboriginal burial sites in south-eastern Australia. Such sites were often placed on the lower sides of hills, though none were the size of the Gingenbullen mound. The placement reflects the significant of nearby Mount Cullingutti, located at the head of the Shoalhaven river on the coast east of Gingenbullen. Cullingutti is a sacred mountain and Dreaming stories are associated with its role as a so-called stairway to heaven or place where spirits go upon death in order to enter a temporary realm prior to rebirth. High places, such as hills and mountains, are usually very significant in regards to the rites and lore of Australian Aboriginal culture and practices, especially in the south-eastern part of the continent.

The woodcut image is shown above as both (1) printed and (2) in reverse, as it was often the case that in transferring an original drawing to an engraved (woodcut or steel) or lithographic plate, it was reversed upon final printing in newspapers or other publications. The reverse image closely aligns with the photograph taken on 31 January 2023 from a similar position next to Oldbury Road. Both are illustrated at the top of this article. The reversed (corrected) image shows an Aboriginal man holding a spear and leaning against a rock by the side of a road, along with scarred trees on both sides and the burial mound on the right side of the road which curves into the distance. The reversed engraving is more in the Picturesque style of the time, with the man on the left looking towards the mound on the right, though it is hard to tell if the man is looking away or towards the viewer due to the low quality of the reproduction. The text of the article accompanying the image reads as follows:

The Native Arts No.1.

In wandering over this vast continent, we cannot fail to be struck with its utter absence of ancient remains. No sign of antiquity exists - not a structure of former art. A piece of common pottery would be an object of interest, and set us questioning: "Who made it, and how long is it since it was constructed?" The native graves - the only artificial elevations we can trace - are of recent date. But, if the field of speculation is limited, it is likely to become lessened, as the Aborigines have almost relinquished the little attempts at art we find. We have mentioned the graves as the only durable constructions existing, and will devote the present paper to the subject, reserving the articles of dress, and domestic and war implements, for a future number. Sir T.L. Mitchell describes the Tombs on the Bogan as covered like our own, and surrounded by carved walks and ornamented grounds; on the Lachlan, under lofty mounds of earth, seats being made around; on the Murrumbidgee and Murray, the graves are covered with well thatched huts, containing dried grass for bedding, and enclosed by a parterre of a particular shape, like a whale boat. Others, on the Darling, were `mounds surrounded by, and covered with, dead branches and pieces of wood. On these lay the singular casts of the head in white plaster.'

We have inspected a grave, or perhaps we might call it a tumulus, which resembled a large hillock some 100 feet long, and 50 in height, and [which] apparently formed the burying place of many persons. The last interred there was the body of an old man, and this was upwards of thirty years ago. The mound is oblong, and to all appearance, entirely formed of earth, probably on a low natural elevation. The large trees surrounding the mound are carved with various devices, and others, at intervals, on the slope leading to the valley below. The tumulus is situated on the level of a mountain side, at an elevation of about 2,700 feet above the sea, and 700 feet above the level of the wooded table land. Below the tumulus, on the slope of the mountain, are extensive marks of excavations of the soil. The construction of this mount must have been a work of labour and time; and, in strong contrast, we may mention a few instances of interments within the last few years.

A native black of the locality died, but was not buried in this tomb - a large nest of the Termites being scooped out, and the body tied into a sitting posture, and enclosed within it. No trees were carved. It was a melancholy instance of the degraded state of the wretched Aboriginal race, as a care of the body of the dead seems inherent in the human breast, in proportion to the advance of civilization. In the case of an infant who died, or was probably murdered, some time since, the corpse was burned and interred in such a shallow grave, that portions of the half consumed bones were perceptible. The accompanying sketch will give a correct view of the locality. Even in connection with the idea of death and mortal decay, it is a pleasing spot, richly clothed with grass and flowers, and shadowed by fine trees, while between the forest boughs we catch a rural scene of fields and dwellings. How great the change from the time when the native blacks toiled in the erection of that tumulus! Now their foot rarely, if ever, treads there, and the sleepers are unknown and forgotten.

--------------------

This important record of the Gingenbullen burial mound - which Atkinson refers to by its scientific term tumulus - tells us the following (comments by the present author are in square brackets):

* It is 100 feet long;

* It is 50 feet high;

* It has the form of a large hillock. [This is similar to an English barrow];

* It is oblong in appearance;

* It is "to all appearances, entirely made of earth";

* It was constructed by Aboriginal people. [The presence of associated scarred trees and the location and form of the mound points to Aboriginal involvement in, and support of the construction, as opposed to any suggestion that it was constructed entirely by Europeans in order to 'hide' a massacre. Nevertheless, Europeans may have been involved in assisting the local people with its construction, though we have no specific evidence for this involvement, and Atkinson was obviously not aware of any at the time of writing her piece. The similarity of the mound to an English barrow would suggest / indicate possible participation by Europeans / British].

* It is located on a level section (terrace) of the mountain side;

* Below it, still on the side of the mountain, are extensive marks of excavation, i.e., movement of dirt and rock from a lower part up to higher ground to form the overlying mound;

* There are "large trees surrounding the mound, ... carved with various devices, and others, at intervals, on the slope leading to the valley below";

* There are trees located within the side of the barrow, suggesting that it was built subsequent to them growing;

* It is apparently "the burying place of many people";

* An old man was buried there "upwards of thirty years ago." [This would be around 1821, when James Atkinson settled at Oldbury, though Louisa's mother had previously stated that the mound was constructed around 1818, prior to the arrival of James].

This tantalising description reveals the significance of the site - a significance which has grown over time as such a large burial mound is not known elsewhere in Australia, at least to this author.

1863

In addition to the above information, a decade later Atkinson published an article in the Sydney Mail on 19 September 1863 which dealt with Aboriginal beliefs regarding death and the afterlife, and repeated much of what she had said in 1853 of the burial mound at Gingenbullen, though with some additions. The relevant excerpt is as follows:

......All the possessions of the dead are buried with them, and anything they may have made use of during their illness. The mode of interment is to confine the bands round the knees, drawing them up to the chest; a shallow grave is then dug, the corpse placed in it, and built over with earth - the stems of the trees in the vicinity being carved with simple devices. On a high hill, a few miles from Berrima, is situated a tumuli. Forty-four years since an old man was buried there; but there is reason to believe the mound contains other remains. The grave is probably one hundred feet long, by forty high, of a gentle conical form, covered with herbage, and surrounded at its base with trees, which, on their sides fronting the mound, were carved in forms suggesting the native shield and boomerang - weapons used chiefly in war. There could be little doubt but what the tumuli is all, or is part artificial, rising thus abruptly from the hanging level in the mountain side; on the slope beneath it are traces of extensive digging and removing of soil, and rocks, and a line of trees are marked to the level, natural cleared, land below; this has given rise to the supposition that the flat has been the scene of a battle, the dead being carried up the hill, and the mount erected by the number of survivors assembled. But beyond supposition nothing can be ascertained. The blacks themselves either cannot, or will not, give any information.

--------------

New information arising from Atkinson's 1863 article includes:

* The burial of the old man took place around 1819, not circa 1821 as previously stated;

* The burial mound is 40 feet high, not 50 feet as previously stated. This could be the result of an error in measurement, or perhaps erosion of the mound, or a different means of taking the measurement, starting at a higher point on the surrounding surface;

* It is "of a gentle conical form";

* "On the slope beneath it are traces of extensive digging and removing of soil, and rocks." In the previous article there was only reference to the use of soil in constructing the mound, and not of rocks.

* It is now covered in herbage, which was not noted in the previous article;

* It is "surrounded at its base with trees, which, on their sides fronting the mound, were carved in forms suggesting the native shield and boomerang - weapons used chiefly in war." No interpretation of the tree carvings was included in the 1853 article, though five were illustrated therein;

* It is suggested ('supposition') by Atkinson that the mound contains the bodies of those killed in a battle between Aboriginal tribes on the flat land below, and in front (west and southwest) of the mountain;

* "The blacks themselves either cannot, or will not, give any information" as to the origins or contents of the burial mound.

For many good reasons, Aboriginal society has traditionally been reticent in regard to publically revealing details of such localities and the spiritual practices associated with death and burial. Likewise, European society has presented a wall of silence around deaths associated with massacres and individual killings of Aboriginal people (Byrne 1998). Both reasons have combined to impose a veil of mystery upon the site - one which threatens its ongoing preservation and protection.

Reasons for silence on the part of Aboriginal communities regarding burial sites include fear of desecration and removal of human remains, as has occurred in Australia since the first days of European settlement, and societal customs which limit access to knowledge around certain ceremonial practices. Whether the Gingenbullen burial mound has been desecrated in anyway as of 2023 is unclear, though the invasive landscaping would suggest that some damage has occurred, in addition to natural erosion and the impact of farming practices since the early 1820s.

The last point would suggest that the mound has special significance. It would also support some of the comments later made by Uncle Gordon Wellington. In addition, the local people perhaps feared its desecration if such information was revealed to Atkinson. They may have been aware of the work of Alexander Berry at the Shoalhaven in digging up the grave of local elder Arawarra during the 1820s and sending parts of his body off to Scotland for study (Longbottom and Organ 2022). Berry was a friend of James Atkinson, and traditionally there were close links between the Aborigines of the Southern Highlands around Moss Vale and Sutton Forest, and the coastal Shoalhaven people. The European invaders had little, if any, respect for Aboriginal bodies during the early colonial period, or, for that matter, Aboriginal society in general. Their scientific curiosity often led to desecration of graves and bodies. On the other side, Aboriginal cultural and spiritual practices and beliefs concerning the subject of death were, and remain, complex and guarded. Louisa Atkinson addresses some of this within the articles she published during 1853 and 1863. However, with regards to the Mount Gingenbullen site, little detailed information was obviously forthcoming from the locals, and perhaps for good reason.

Knowledge regarding the subject of death and burial from similar sites such as Mount Cullingutti on the Shoalhaven river (from 1821 part of the Alexander Berry Estate), Gulaga / Mount Dromedary near Tilba Tilba, and Mount Keira near Wollongong, suggests the following:

* Mountain peaks and high places were often significant sites of ceremony, ritual, spiritual belief and art.

* Mountain peaks and high places were also associated with corroboree sites and bora (initiation) grounds on the lower, flat-lying land at their base.

* Mountain peaks could perform a 'stairway to heaven' equivalency, from where the spirits of the dead would set off on their afterlife journey, as was the case with Cullingutti.

* Specific male and female mountain peaks and high places are known, taking up whole or part of such sites.

* Burials are known to have taken place on the lower sides of hills and mountains.

* When travelling, Aboriginal people in the area of Australia would often take a route over the highest point in the landscape, rather than a low path around, much to the chagrin of Europeans accompanying them.

The precise significance of Mount Gingenbullen is not known to this author, apart from what is recorded in the Atkinson articles, and some of the aforementioned attributes highlighted by Uncle Gordon Wellington. It should also be noted that Gingenbullen has both a peak and ridges, therefore there may be a number of different areas of the mountain that have specific cultural significance, such as regards ceremony, story-telling, or burial. The Atkinson house was located on low-lying land upon Mount Gingenbullen's north-western flank, with the burial mound located on a terrace close by, and slightly above it. It is possible, indeed likely, that when he initially acquired the Oldbury grant, James Atkinson was warned off by the local people from erecting his house so close to the burial mound and graveyard. He obviously chose to ignore any such advice as the location was close to a natural spring and flat lying land suitable for agriculture. The local people may also have been reticent to outline the full extent of their concerns to the new settlers, leaving the Atkinsons in the dark as to the mound's significance.

-------------------

6. Another burial mound

A similar, much smaller, contemporary Aboriginal burial mound was illustrated in 1817 by the surveyor George Evans in Wiradjuri country near Condobolin, on the Lachlan River, approximately 400 kilometres northwest of Mount Gingenbullen. It had initially been recorded by Surveyor General John Oxley on 29 July 1817.

|

| G.E, Evans, Grave of a Wiradjuri man at Gobothery Hill, near Condobolin, 1817. |

Evans' watercolour Grave of a Wiradjuri man at Gobothery Hill, near Condobolin, 1817 (State Library of New South Wales) was reproduced as an engraved print in John Oxley's Journals of two expeditions into the interior of New South Wales, undertaken by order of the British government in the years 1817–18 (Oxley 1820). The site is currently referred to as King's Grave. From the Evans illustration we can see that the burial mound is located on the side of a hill (Gobothery Hill), is of conical shape similar to the Gingenbullen profile, has lines marked in the ground to the right, and is flanked by two scarred trees, again similar to the Gingenbullen site. There are, as a result, similarities between the Evans watercolour and the Atkinson print. The Gobothery Hill site is extant, though the mound has been flattened out to a large degree (again, similar to Gingenbullen). As the supposed burial site of a single individual, it is also very much smaller than the Gingenbullen burial mound. This site was also sketched by explorer Charles Sturt during the late 1820s, showing slightly different landscaping and three scarred trees.

|

| Charles Sturt, Burial Place near the Budda, frontispiece to Two Expeditions into the Interior of Southern Australia, 1828-31. |

A copy of Sturt's sketch was made and printed by William Blandowski. The term 'the Budda' possibly refers to the Bogan River.

|

| William Blandowski, Plate 137: Aborigines of Australia: burial places near the Budda in longitude 148° latitude 32° from a sketch by Capt. Sturt. |

The similarity between the composition of the Sturt / Blandowski sketch / print and the later 1853 engraving by Louisa Atkinson can be noted, with an Aboriginal man seated against a tree, spear in hand, present in all three.

------------------------------

7. Possible Origins

The question must be asked: What does the burial mound contain, and why is it so big? No precise answers have officially been provided by the local Indigenous population, either in the past or recent times. The Atkinsons were informed that it was the site of a number of burials, but nothing more was forthcoming. Uncle Gordon Wellington referred to it containing one of his ancestors. The largeness of the site as described is extraordinary and it appears unique in the Australian context. Large ancient burial mounds are known throughout the world, including the famous barrows of Great Britain and Europe, but not in Australia. The size and location suggest a number of scenarios regarding the possible origin and content of the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound:

a) Tribal warfare: Louisa Atkinson suggested (1863) that the site contained the bodies who those who died as a result of a battle between local tribes around 1817-18, perhaps held on the flat land below Gingenbullen. As she says, there is no specific evidence for this and it is pure supposition / speculation on her part. Elements of the suggestion nevertheless ring true. We do know that in 1830 there was a battle between the Bong Bong tribe and Illawarra tribe at Fairy Meadow, and it was recorded that approximately 100 men died (Organ 1990). Therefore, such battles did occur. In that instance, the bodies were buried locally in the sandy soil around the Fairy Meadow wetlands, and no mound, or mounds, are known to have been constructed. No large battle on the Gingenbullen site has been recorded prior to 1821, unlike the later Fairy Meadow event. As there was European presence in the region at the time, and individuals such as Charles Throsby had close ties with the local people, it is likely that if such a battle had occurred at Mount Gingenbullen in the immediate years prior to Atkinson's arrival, then details would have been known.

b) Mass poisoning: Dr. Illert has suggested that the mound is the burial site for a massacre which supposedly took place on the Oldbury estate and was carried out around 1821 by the new landowner James Atkinson, father of Louisa Atkinson (Illert 2018). Illert suggests that water and sugar laced with poison was used, based on a comment in a Louisa Atkinson article which notes the rumoured use of such, though not necessarily at Oldbury. However, there is no convincing evidence for such a massacre, and the present author rejects it, based in part on the seemingly good relations Atkinson subsequently had with the local Aboriginal population, few though they apparently were. More importantly, Moss Vale historian Narelle Bowern presents a solid argument against this specific allegation in her study of the early contact history between Europeans and the Aborigines of the Southern Highlands (Bowern 2018). She also points out therein that the burial mound was constructed prior to Atkinson's arrival at Gingenbullen.

c) Government sanctioned massacre: The current author proposes a possible link to the Appin massacre of 1816, with the bodies from the massacre buried at Mount Gingenbullen. During 1816 Governor Lachlan Macquarie initiated several secret punitive military expeditions in association with his official declaration of war against the Aborigines of the Sydney district. Early in the morning of 17 April of that year, and under cover of darkness, a group of people were massacred near Appin by one of his elite Grenadier military regiments. Those killed in the now infamous Appin massacre of 1816 included a group of women, children, old people and two men camped near Broughton's Pass, south of Appin. One of those massacred was the aged Canabygle, chief of the Aboriginal people of the area from Picton south to Bargo, Mittagong, Moss Vale and beyond Mount Gingenbullen towards Bundanoon and Tallong. Governor Macquarie in 1820 referred to the northern part of that area as Canabygle's Plains. This latter location is indicated in yellow on the map below, with a red cross showing the massacre site to the northeast, and a green cross indicating Mount Gingenbullen to the southwest.

|

| X - Appin massacre site; X - Cannabygle's Plains; X Gingenbullen |

Canabygle's people were only visiting the Appin area at the time, as it was not their Country. They had been forced by an extended drought since 1814 to come in closer to Sydney for food. They were at Broughton Pass, Appin, on the night of 17 April 1816 when attacked and massacred by Macquarie's armed troops. Since 1814 people from the west (the Gundangara) and east (Dharawal) of the Sydney Basin also came closer in to the new settlement due to widespread drought limiting the supply of food. There was also a long tradition of the movement of clans and tribes in association with events such as corroborees, marriage and conflict. Canabygle, who his descendant Francis Bodkin cites as one of the near coastal Dharawal people, was also acting as an intermediary between the Mountain tribes - the Gundangara - and the Sydney people, facilitating the sharing of resources during this difficult period (Bodkin 2014 & 2015). Members of the Gundangara tribe had carried out retaliation to barbarities by European settlers. As a result, Macquarie decided to crack down on all the Aboriginal people in the region. He declared war against them, and sought to terrorise them. Canabygle and his tribe were unfortunately caught in the middle of this, and slaughtered by the troops, with guns and bayonets.

It is possible that the 14 plus bodies of those killed at Appin were subsequently, and secretly, recovered by local people - with assistance from supportive, compassionate settlers such as Charles Throsby of Moss Vale - and taken to nearby Mount Gingenbullen for a safe, traditional burial. It is known that the body of Canabygle and another man were initially taken from the massacre site and strung up on a tree on a hill near Appin to strike fear amongst the surviving Aborigines. The two bodies of the men, along with that of a female, were subsequently violated. Canabygle's head was cut off, sold and shipped to a university in Scotland, along with that of the unknown male and female. Perhaps the bodies then buried by the soldiers in shallow graves near the massacre site, and subsequently exhumed by his surviving tribal friends and family.

|

| Known victims of the Appin massacre, 17 April 1816. |

In a discussion regarding this scenario, between the current author and a local First Nations person from Bundanoon during January 2023, it was suggested that the bodies of those killed would have been buried close to the massacre site, and not transported the seemingly long distance south to Gingenbullen. It is also noted above that Aborigines were abhorred at the thought of exhuming a body. It is nevertheless the view of the present author that it was considered appropriate that the unburied bodies of the victims of the Appin massacre - the first officially sanctioned massacre in Australian history - be buried according to traditional custom and with due respect. Therefore, transported to the Gingenbullen graveyard in the immediate aftermath of the massacre was acceptable and appropriate. It is therefore possible that the interred, decapitated body of Canabygle - perhaps the 'old man' noted by Louisa Atkinson - was subsequently exhumed (if, indeed, the soldiers had bothered to bury it) and laid to rest in the mound at Gingenbullen, beside a carved tree which noted his importance to the local people. Verification of the truth or otherwise of this proposition rests with the archaeological investigation of the burial mound, and/or corroboration from within the surviving Aboriginal community and knowledge holders. [NB: Refer the section below for more information on the 1816 Appin Massacre.]

d) Pandemic: The mound may contain burials resulting from a single, mass pandemic such as smallpox, influenza or tuberculosis introduced by European settlers and explorers. It is known that pandemics had a devastating effect on the Aboriginal population around Sydney and nearby areas from as early as 1789. There is no specific evidence for this having occurred around 1816-18 near Oldbury / Sutton Forest.

e) Graveyard: The area of the burial mound appears to have been a long-standing graveyard. The placement of a group of bodies, due to a single massacre or other event, may have been seen of such significance that the additional material was placed on the site to signify this.

It is important that archaeological investigations be carried out at Mount Gingenbullen to determine the precise extent of the surviving burial mound and any surrounding burials.

---------------

Historical Background - A Chronology

8. Cannabygle's Tribe & the 1816 Appin Massacre

The association of the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound with the 1816 Appin Massacre is tenuous due to the lack of surviving records from around this period, and the nature of the event - one which would be kept hidden by both Europeans and the local First Nations people. Yet there appears to be a close link between the area and the Dharawal tribe headed by Canabygle (c.1760-1816). According to a brief biography of Canabygle published in October 2021 by Dr. Joseph Davis, and a comment published in a British book on phrenology in 1820, Canabygle was the "chief" of a tribal area possibly stretching from Picton south to Tallong and covering the area now known as the Southern Tablelands in between (Davis 2021). As the collector of his skill in 1816, the somewhat biased Dr. Patrick Hill noted:

I may observe, that Carnimbeigle was a most determined character, one of the few who were hostile to the settlers, and who annoyed them very much by destroying their cattle. A party of the military were sent out against him and his confederates; but he could not be found, until they procured two native guides. He was then traced to his den, and, being placed at bay, he died manfully, having received five shots before he fell (Patrick Hill, quoted in Sir George Mackenzie, Illustrations on Phrenology, London, 1820).

Canabygle's Plains were referred to both by one of the soldier's on Macquarie's punitive expeditions of 1816, shortly after Canabygle's death at Appin, and by the Governor himself in 1820. Davis cites historical references to Canabygle from 1800 through to his murder in 1816, and thereafter in reference to Canabygle's Plains located in the vicinity of, and on the northern side of Mittagong. Gingenbullen is included within Canabygle's area of influence, similar to Moyenguley's subsequent role as "chief" of the Nattai region to the northwest.

The issue of past and present familial, clan, tribal, nation and language associations and boundaries is complex, especially due to the imposition of Western civilisation classifications since 1788. We can see, for example, from historical documents, that the people of the Southern Highlands area had a close association with the coastal people of the Illawarra, and together are referred to within the famous Tindale map of 1946 as the Dharawal. The Gundungurra were traditionally the people associated with areas to the west, around the Nattai and Burragorang valleys. With Canabygle's tribe covering a thinnish area of land trending north-south along the western edge of the Illawarra and Shoalhaven escarpment, it is reasonable to include Mount Gingenbullen as within the southern part of this "country", and therefore obviously one of the centres of ceremony and gathering, as also possibly would have been Mittagong's Mount Gibraltar. Defining the precise boundaries of the "country" claimed by various tribes during this early colonial period is almost impossible, as is the mapping of language boundaries. However, the distinctions between the coastal, highlands and inland people at this time appear to be relatively clear, with some obvious overlap.

One other element of the massacre is the fact that Governor Macquarie had apparently listed Canabygle as one of the 'wanted' Aborigines to be shot and killed on sight, in retaliation for 'depredations' against white settlers. Judging from surviving archival records, which of course only provide the European side of the argument, it appears that near Appin the wife and five children of the Gundangara Aboriginal men Bitugally and Yelloming (Yellowman) were brutally murdered by two white men, including a soldier, during 1814, and that, in reprisal, a European woman was killed, possibly by members of the Gundangara tribe then present in the region due to drought. This was in line with traditional Aboriginal lore, unrecognised by British law. The retaliation which resulted in the murder of 14 members of Canabygle's tribe was typical of European treatment of First Nations peoples during the first century and a half of white settlement, with an inordinate response by the authorities and unrestrained settlers and convicts to 'native outrages' which were often brought about by European killings and abuses.

-----------------

9. 1821-22 Occupation of Gingenbullen / Oldbury Estate

8 March 1822, Sydney Gazette: James Atkinson occupied Mount Gingenbullen shortly after receiving his initial grant in 1821. It was supplemented the following year and comprised 2,000 acres.

Caution. — The Farms of Oldbury and Newbury, situate in the District of Sutton and County of Argyle, having been some Months since marked out and located, and being now in the Occupation of the undersigned; all Live Stock, found grazing or trespassing on the same, will be impounded. James Atkinson, Sydney, March 7, 1822.

-----------------

10. 1826 - James Atkinson's map

In 1826 James Atkinson published An Account of the State of Agriculture and Grazing in New South Wales (Atkinson 1826). It contained a large map of the colony, a section of which is included below. This provides some contemporary context to locations discussed within this article. Sutton Forest and Oldbury can be seen in the geographical area lined in yellow and called Argyle.

-----------------

11. Subdivision and sale of the Oldbury Estate 1887-91

The Oldbury Estate of approximately 2,000 acres was subdivided and sold by the Atkinson family at a public auction in Sydney during 1887. A poster advertising the sale is reproduced above. The estate was sold in 47 lots of varying size. The burial mound and graveyard was located within lot 29, which included Oldbury House. The subsequent sale history of the land is not known, apart from the following notes below.

* 8 July 1891, Bowral Free Press: Oldbury Estate. Messrs. Nicholson Bros. report having sold on Saturday last, in conjunction with Messrs. Richardson and Wrench, the unsold portion of Oldbury estate, Sutton Forest, comprising house and about 112 acres of land, to Mr. A. D. Badgery, of Sutton Forest, at a very satisfactory price.

-----------------

12. 1899 Parish Map

The County of Camden, Parish of Bong Bong map of 6 February 1899 refers to Mount Gingenbullen as Tillynanbulan Mt., with reference to the Gingenbullen trig station.

|

| 1899 Parish of Bong Bong map (extract). |

-----------------

13. The 1929-32 Blue Metal Quarry

Between 1929-32 a railway line 4.14km long was constructed from Berrima Junction to Gingenbullen by Blue Metal Quarries Ltd to service a quarry operating on its northern side (refer map below).

|

| Gingenbullen blue metal quarry, circa 1929-1932. |

It is said that some 300,000 tons of rock was mined from the site during its brief opening. A number of explosions there took place resulting in the death and maiming of several Serbian workers. The line and quarry were dismantled in 1942 (Australian Railway Historical Society Bulletin, February 1959 and no.508, February 1980). Recent aerial photographs of the site (viz. Google Maps) indicate the boundaries of the excavation and fortunately indicated that it did not have had any impact upon the suggested burial mound and nearby graveyard site to the north west.

-----------------

14. Uncle Gordon Mitchell Wellington reminiscences 1930s-1990s

Uncle Gordon Wellington (1916-2000) regularly visited the burial mound at Mount Gingenbullen from the 1930s. Some of his reminiscences are included at the beginning of this article, significantly referring to his annual visits during the last decades of his life, and the events which took place there. An obituary published during 2000 contained comments by Wellington on the aspect of proposed residential development of, and encroachment upon, the Aboriginal sacred site of Mount Coolangatta, located near the mouth of the Shoalhaven River and nearby burial sites. His comments could similarly apply to Mount Gingenbullen:

... Houses don't belong there. They will become haunted and the owners will become cursed without ever knowing why. (Illert 2000)

The question arises - is Oldbury therefore cursed? Some of Uncle Gordon's comments would suggest this, as do events in recent history. It is telling that James Atkinson suffered an early, tragic death in 1834, aged just 38; his overseer George Bruce Barton - who thereafter married Atkinson's wife Charlotte - went insane during the 1840s; James and Charlotte's daughter Louisa died at a similarly young age (38); and Louisa's brother James John only lived to 52. In addition, it took Charlotte (Atkinson) Barton decades to regain access to, and ownership of, the Oldbury Estate, following the illness of her second husband. Were the Atkinsons cursed as a result of the placement of the Oldbury homestead so close to the Gingenbullen burial mound and graveyard? It is possible, especially if we consider the words of warning of Uncle Gordon Wellington.

----------------------

15. The Lampert Report 1994

During September 1994 retired Sydney anthropologist R.J. Lampert visited Mount Gingenbullen. He had become aware of the Atkinson published material on the burial mound and, guided by local resident Jeff McDonald, was taken to a site behind, and 200 metres above Oldbury House (i.e. south-south east of the house). This was not the site as described above. In a draft report dated November 1994 Lampert recorded the following findings:

Mr McDonald knows of Louisa Atkinson's description of the [burial] site and says there was only one possible location, on a broad natural terrace at the west north-western end of the mountain, immediately behind, but 200 metres above, Oldbury House.... I scaled the mountain with Mr McDonald in September this year. On reaching the site we found it to be grossly degraded by European land use..... The natural terrace depicted by Atkinson was recognisable, but of the burial site itself no evidence could be seen.... Mr McDonald said that a mound about 1.5 metres in height, which he assumed was a remnant of the burial mound described by Atkinson, once stood on the outer edge of the terrace but "the soil conservation people" had pushed it down slope to build a dam just below the terrace. The burial site described by Louisa Atkinson, as well as the "pleasing spot" at which it had been located, had entirely disappeared.... I felt depressed, not only because of the disappearance of an Aboriginal site, but also because of the gross environmental degradation that had been brought by 150 years of European land management. (Lampert 1994)

In the view of the present author, Lampert was taken to a site on the side of the mountain that was not the site as described by Louisa Atkinson over a century before, but much higher up and to the south-south-east. For this reason, the anthropologist came to believe that the Atkinson burial mound had been destroyed, and wrote as much somewhat dejectedly in his report. It is likely that Mr McDonald knew of the hillock closer to Oldbury House and next to Oldbury Road, having apparently visited Oldbury during his youth, but perhaps did not consider it to be an Aboriginal burial mound due to its extreme size. As a result, an important opportunity was lost, and Lampert left the area that day "depressed" at the thought of the destruction of such an historically and culturally significant Aboriginal burial mound.

-----------------------

16. The Kim Leevers thesis 2006

In 2006 a thesis was published by Kim Leevers, a student at the University of Wollongong, entitled First contact / frontier expansion in the Wingecarribee area between 1798 -1821: Exploration and analysis. It included the findings of Lampert's draft report of 1994, suggesting that the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound no longer existed. The Leevers reference is as follows:

Lampert, an anthropologist from the Australian Museum, who investigated the area in 1994, located the natural terrace, but was advised that a mound of about 1.5 metres (approximately 5 feet), had been bulldozed down the slope to build a dam. There was no evidence of carved trees but that is not surprising after one hundred and seventy years or so. If the tumulus existed it requires a more detailed and forensic study to identify its location and contents. (Leevers 2006, 77)

It is unclear if Leevers visited the grounds of Oldbury House and/or the location of the burial mound as described above.

17. Representations to Government 2006

During 2006 various development proposals in the vicinity of Mount Gingenbullen were submitted to Wingecarribee Shire Council for approval. The Northern Illawarra Aboriginal Collective (NIAC), representatives of the local Dharawal people and which had Uncle Gordon Wellington as a member prior to his death in 2000, made a number of submissions to the New South Wales Department of Environment and Conservation, calling for prior preparation of relevant Aboriginal heritage assessments of the area. Some of these submissions are referred to below, though apparently no action was taken in regard to Mount Gingenbullen at that time.

* 1 February 2006 - In regard to a proposed development of the Sutton Forest Hotel, the Northern Illawarra Aboriginal Collective (NIAC), representing Dharawal peoples, called upon the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) to consider:

... the proposed development site and adjoining landscape is a major massacre site which may well need to be deemed an Aboriginal Place of State Significance. The proposed development occurs on part of a landscape which includes the famous Mount Gingenbullen (an Aboriginal name).. The landscape is so important, and the disposition of 200 known skeletons is so poorly documented, that we ask DEC to refuse any S90 consents... (NIAC 2007)

* 15 March 2006 - The Northern Illawarra Aboriginal Collective (NIAC), representing Dharawal peoples, called upon the Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) to:

.... urge the NSW-NPWS to declare the entire countryside about Mount Gingenbullen, out to .... a five kilometre radius, an Aboriginal Place of State Significance and to freeze .... development proposals. (NIAC 2007)

* Traditional Owners Snubbed, Southern Highlands News, 15 April 2006. Report on Wingecarribee Shire Council approving rezonings and development proposals without corresponding Aboriginal heritage assessments, as requested by NIAC and other groups and individuals.

-----------------

18. The Simms' & Illert site visit 2007

During December 2007, in association with preparation by the Northern Illawarra Aboriginal Collective (NIAC) of their Report on Wongonbra proposed 400ha subdivision application, Dharawal men Keith Simms Snr and Keith Simms Jnr, accompanied by Dr. Chris Illert, visited the site of the Gingenbullen burial mound and spoke to the owner of the property. Dr. Illert had previously interviewed Uncle George Wellington and was aware of the cultural significance of the site. As this section of Mount Gingenbullen was outside the area of the proposed Wongonbra subdivision, no detailed archaeological investigation was required, or undertaken, at the time. The Simms' and Dr. Illert saw the burial mound in the area indicated above and as previously described by Uncle Gordon Wellington. They also noted that the owner was seeking to build a driveway in the mound's vicinity and had contact the Wingecarribee Shire Council in that regard. There had apparently been a negative response to the development proposal by Council, though the landscaping observed by the current author in February 2023 would indicate that work was eventually carried out by the owners of the property.

-----------------

19. Landscaping report circa 2014

A circa 2014 blog by UK garden designer Janna Schreier, describes the extensive landscaping and garden design work carried out in the area of the burial mound by then owners of the Oldbury Estate, Chris and Charlotte Webb. Whilst there is no reference therein to the burial mound, there is to an 'orchard with mixed fruit trees, including lemon' which appears to be located in the region of the mound. The layout of this area, to the north of Oldbury House, is seen in the 24 January 2023 Google Maps satellite image reproduced above.

-----------------

20. The Hume Coal inquiry 2017

During 2016-17 Hume Coal proposed developing a coal mine and rail line in the region of Sutton Forest and Mount Gingenbullen. David M. Newby, at the time owner of 220 acres containing Oldbury House and the burial mound / graveyard land, sent a letter of objection to the proposed mine to the Department of Planning and Environment (Newby 2017). He therein outlined the heritage significance of the house and gardens, and the threat that undermining the property would pose to his use of groundwater for cattle and irrigation.

A detailed archaeological investigation was carried out on behalf of Hume Coal in an area close to Mount Gingenbullen (to the west and south), but not within the likely burial mound site location referred to above. A number of reports were prepared, including three volumes on Aboriginal Cultural Heritage. These are available online here. Therein passing reference was made to the burial mound, quoting landscape heritage consultant Colleen Morris. It pointed to the lack of specific detail available in regard to the burial mound; it did not attempt to precisely locate the burial mound, as 'The archaeological survey team for the project were unable to access the alleged location as it is outside of the project area and on private property'; and it focused on debunking Dr. Illert's claims that it was related to a massacre. This is seen in the following extract from the report:

24.7 Gingenbullen Aboriginal burial mound: A submission by [landscape consultant] Colleen Morris stated the following: "With respect to the Aboriginal history of the area (Hume Coal Appendix S Table 2.3 Point 3), during research for the Berrima, Sutton Forest and Exeter Cultural Landscape Assessment it was found that there is serious doubt as to the claim of a massacre site on Mt Gingenbullen. The claim is based on a publication in which the author selectively uses source material in a debatable manner. Unfortunately this claim detracts from the real value of the history of the site, which was a genuine Aboriginal burial mound, at Mount Gingenbullen." EMM acknowledges that there still remains some uncertainty about the specific nature and location of the alleged burial mound near, or on, Mount Gingenbullen. The archaeological survey team for the project were unable to access the alleged location as it is outside of the project area and on private property. Notwithstanding, the project will not impact this area or nearby as the surface disturbance footprint of the rail corridor is approximately 2.5 km north of the alleged location and the surface infrastructure area is approximately 4.5 km to the north-west.

This comment suggests a number of things;

- Landscape heritage consultant Collen Morris, who is also cited as a representative of the local Aboriginal community, was aware of the story of a burial mound on Gingenbullen.

- The archaeological investigation team did not visit the site.

- Morris was not able to obtain information on the precise location of the burial mound.

- The report classifies the burial mound status as "alleged".

- The report implies the burial mound may no longer exist.

- Morris rejects Dr. Illert's claim to a "massacre site" on Gingenbullen.

This report further suggests that precise archaeological information regarding the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound did not exist in official records during 2016-17. It is likely that this situation remains in place. It therefore appears that no substantive archaeological investigations have ever been carried out to precisely reveal the location, extent and significance of the burial mound, though informal discussions by the author during 2023 suggest that the local First Nations community is aware of the site, as is (possibly) Wingecarribee Shire Council.

----------------------

21. The case to ignore

As can be seen from the above information, the recent history of the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound is shrouded in mystery, leading to the confusing information presented as part of the Hume Coal inquiry. For example, Morris, in her May 2017 Cultural Landscape Assessment - Berrima, Sutton Forest, Exeter Area, cites Kim Leevers' 2006 University of Wollongong thesis, which in turn references the 1994 document by R.J. Lampert. As a result of this research, Morris concludes:

The mound is no longer evident (Morris 2017, 71).

The present author disagrees with this statement. Morris also adds a footnote regarding the Leevers thesis:

In Kim Leevers' thesis he states that anthropologist R.J. Lampert, who investigated the area in 1994, was informed that a mound had been bulldozed down the slope to form a dam. There was no evidence remaining of carved trees. (Morris 2017, 71)

It seems strange to the present author that Morris, not having visited the site, should somewhat emphatically conclude that the mound is no longer evident.

It is also strange that Lampert, who did visit a site at Mount Gingenbullen and apparently located the natural terrace [mentioned by Louisa Atkinson], should question if the tumulus existed after being informed of the destruction of a very small mound. All of which suggests that Lampert was in the wrong place and did not see the site which is reproduced in a photograph at the top of this article, and below. It also raises the possibility that more than one burial mound was located on Mount Gingenbullen.

|

| Panoramic view of the burial mound, looking east-northeast from Oldbury Road, 31 January 2023. |

As a result of the above, the comments by the two professionals - an anthropologist and a landscape heritage consultant - who have commented on the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound to date, has only resulted in confusion, due to the fact that they did not actually visit the site of the mound as described by Louisa Atkinson and within this present article. They have presented a case to ignore the existence of the Mount Gingenbullen burial mound.

--------------------

22. Conclusions

1) The Mount Gingenbullen Aboriginal burial mound, as described by members of the Atkinson family between 1841-63, and Uncle Gordon Wellington (prior to 2000) is the largest such site known in Australia, originally described as 100 feet long and 50 feet high.

2) The existence of the burial mound has been precisely located and identified by a number of people, most recently during February 2023.

3) The site requires listing in official Local, State and Federal government registers as an archaeological site, an Aboriginal Place, and a First Nations Place of national significance.

4) Appropriate archaeological investigations must be carried out, in collaboration with relevant traditional knowledge holders, to more precisely define the history, nature and present physical condition of site.

5) Measures must be put in place to protect and preserve the site and ensure that its desecration does not take place, and that any such elements of desecration to date be removed as part of its restoration and protect.

6) The site may be associated with the Appin Massacre of 17 April 1816.

-------------------

23. References

Atkinson, James, An Account of the State of Agriculture and Grazing in New South Wales, J. Cross, London, 1826, 146p.

-----, The Australian Farmer's Assistant, Australian Almanack for the year of Our Lord 1832, Robert Howe, Sydney, 1828-33, 17-28.

Bodkin, Francis, Appin massacre – April 1816 [video], A History of Aboriginal Sydney [website], University of Western Sydney, 27 February 2014. Duration: 5 mins 8 secs. Available URL: http://www.historyofaboriginalsydney.edu.au/south-west/appin-massacre-april-1816-frances-bodkin.

-----, The Appin Massacre 1816, in Peter Read, Aboriginal narratives of violence, Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues, 18(1), 2015, 75-85.

Bowern, Narelle, The Aborigines of the Southern Highlands (1820-1850), New South Wales, Moss Vale, 2018.

Caroline Louisa (Waring) Calvert Atkinson (1834-1872), WikiTree [website], accessed 14 February 2023.

Charlotte (Waring) Atkinson Barton (1796-1867), WikiTree [website], access 14 February 2023.

Davis, Joseph, Indigenous Dispossession, Decapitation and Child Abduction on the Plains of Cannabygle (1800-1816), academia.edu, October 2021, 14p.

Forsyth, Kate and Belinda Murrell, Searching for Charlotte: The Fascinating Story of Australia's First Children's Author, National Library of Australia Publishing, Canberra, 2020, 304p.

Illert, Chris, The Last Shoalhaven Lore Master - Gordon Mitchell Wellington, Shoalhaven Chronograph, August 2000, 1, 5.

-----, Three Sisters Dreaming, or, did Katoomba get its legend from Kangaroo Valley?, Shoalhaven Chronograph, Shoalhaven Historical Society, 2003, (Special Supplement), 40p.

Byrne, Denis, In sad but loving memory - Aboriginal burials and cemeteries of the last 200 years in NSW, Cultural Heritage Division, Department of Environment and Climate Change, Hurstville, 1998, 52p.

Jervis, James, A History of the Berrima District, 1798-1973, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1986, 213p.

John James Atkinson 1832-1885, WikiTree [website], accessed 14 February 2023.

Lampert, R.J. [Ronald John], Mount Gingenbullen as seen by Louisa Atkinson and recent observers, draft essay, November 1994, 3p.

Leevers, Kim, First contact/frontier expansion in the Wingecarribee area between 1798 -1821: Exploration and analysis, BA(Hons) thesis, University of Wollongong, 2006, 97p.

Longbottom, Marlene and Organ, Michael, Alexander Berry, grave robbing and the Frankenstein connection, [Blog], 5 February 2022.

Mackenzie, George, Illustrations on Phrenology, London, 1820.

Morris, Colleen, Cultural Landscape Assessment: Berrima, Sutton Forest, Exeter Area, May 2017, Report for Hume Coal, 170p.

-----, Statement of Heritage Impact for Berrima, Sutton Forest and Exeter Cultural Landscape of Hume Coal Proposal for an underground coal mine and Berrima Rail line extension, June 2017, Report for Hume Coal, 43p.

Newby, David M., Objection to Hume Coal Development Proposal [manuscript letter], submission to New South Wales Department of Heritage and Environment, 5 June 2017, 2p.

NIAC, Report on Wongonbra proposed 400 ha Subdivision Application, Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Assessment, Northern Illawarra Aboriginal Collective Incorporated, January 2007, 13p.

Organ, Michael, Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1850, Aboriginal Education Unit, University of Wollongong, 1990, 630p.

-----, Bundanoon - Notes on Aspects of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage - Part 1 to 1850, [Blog], 29 October 2022.

-----, Bundanoon - Notes on Aspects of Aboriginal Cultural Heritage - Part 2 from 1851, [Blog], 8 November 2022.

Oxley, John, Journals of two expeditions into the interior of New South Wales, undertaken by order of the British government in the years 1817–18, John Murray, London, 1820.

Robertson, William A., A Palaeomagnetic Study of Igneous Rocks from Eastern Australia, PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, September 1962, 181p.

-------------------

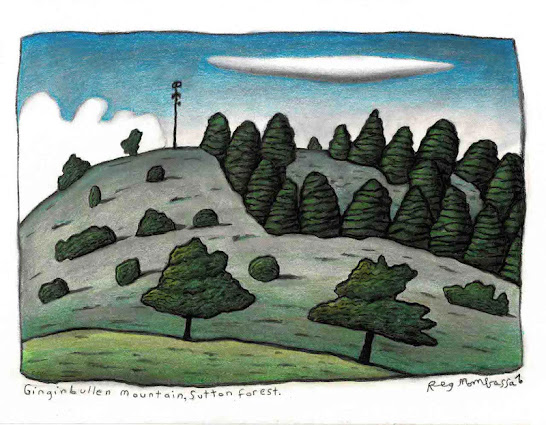

|

| Reg Mombassa, Gingenbullen Mountain, Sutton Forest, print, c.2020. |

24. Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Dr. Chris Illert for his inspiration, research, and assistance in developing this article. Though we may not agree on the precise history of the site, we are both of the strong belief that it is one of the most significant Aboriginal burial sites in Australia. Also thanks to Amie Hunter in identifying aspects of the location and sharing her enthusiasm for the Aboriginal cultural heritage of the Bundanoon area.

| Australian First Nations Peoples / Aborigines research | Appin massacre 1816 | Canabygle | Cook 1770 & Appin 1816 | Dreaming Stories | Gingenbullen | Illawarra & South Coast a & b | Macquarie's War 1816 | Origins 130,000yrs+ | Pituri | Southern Highlands |

Last updated: 22 October 2024

Michael Organ, Australia (Home)

Comments

Post a Comment