The faërie realm of Joan Lindsay's Picnic at Hanging Rock

Picnic at Hanging Rock: Chapter 3 & 18 | Disappearance @ Hanging Rock (film script) | Faerie in Australia | Path of Light (book sequel) | Picnic & the Faërie Realm | Posters |

|

| Joan Lindsay, circa 1922. |

Contents

- Introduction

- Origins, ancient & modern

- Joan's story

- The disappearance

- The Secret of Hanging Rock

- Faërie realm

- Fairy Crab

- The 2018 TV series

- Joan Lindsay and time

- "A dream within a dream"

- Martin Sharp, Botticelli & Tchaikovsky

- Miranda Must Go!

- The End

- Appendix 1: Chronology

- Appendix 2: Historical research

- References

- Acknowledgements

------------------

Abstract: The mystery at the heart of Australian author Joan Lindsay's 1967 novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, the 1975 film version by director Peter Weir, and the 2018 television series featuring Natalie Dormer, can only be understood, and partially solved, when consideration is given to the faërie realm context in which the narrative was originally set by the author. The faërie realm is a dimension wherein space and time differ from the normal, earthly reality. Faërie is an English term referring to mythical or real creatures, elementals, and sentient beings that may have supernatural powers and usually occupy a dimension not aligned with the human reality but, at times, overlapping. Encounters can be short or long, multidimensional, serendipitous or planned, fruitful or frightening, and incidental or fateful, as was the case in Joan Lindsay's novel. Due to a reticence on the part of the Australian audience, or rather, ignorance in regard to this largely British perspective, the trippy final chapter of Lindsay's original 1966 manuscript was deleted by the publisher prior to publication of the novel at the end of the following year. That expunged chapter highlighted, and expanded upon, the faërie context and, in part, the mysterious disappearance of the three schoolgirls and their teacher. Lindsay, who died in 1984, redressed the deletion by putting in place during 1972 a process whereby it would see the light of day upon her passing. This took place in 1987, though it has been largely ignored since then. The present article highlights the impact of the decision to delete the final chapter, outlines its content, and discusses Joan Lindsay's lifelong engagement with faërie and aspects of the paranormal. It also recommends the publication of an updated version of Picnic at Hanging Rock which incorporates the deleted final chapter, as originally intended by the author.

Editorial Notes: Whilst the present author believes in the existence of the faërie realm, it is not necessary for the reader to hold a similar view in order to understand, appreciate or accept the arguments and conclusions presented herein. A YouTube video of an earlier version of this article is available here. Quotes are from Picnic at Hanging Rock (Lindsay 1967) unless otherwise indicated. Page number citations from the 1967 edition of Picnic at Hanging Rock - appearing as, for example, [115] in brackets - are taken from the searchable Google Books online edition. Throughout this text, the original 16th century spelling faërie is favoured, though elsewhere fay, fairy or faerie are utilised within their broadest context.

------------------

Joan Lindsay & Picnic at Hanging Rock

I write sitting on the floor, surrounded by sheets of paper in a sort of fairy ring. It’s bliss. (Lindsay 1962)

For me, who knew Mount Macedon and Hanging Rock, the story is entirely true. (Lindsay 1967)

I can only say that for me, fact and fiction are closely allied. Some of it really happened, and some of it didn't. And to me, it all happened. It was all terribly true for me. (Lindsay1974)

I can't tell you whether the story is fact or fiction, or both. But a lot of very strange things have happened in the area of Hanging Rock, things that have no logical explanation. (Lindsay [1985])

1. Introduction

How does one explain the sudden disappearance, and/or reappearance, of a thing or person, perhaps before one's very own eyes? Is it simply a magic trick, or something more otherworldly and perhaps even sinister? And what if that thing or person disappears and never returns? Where does it go? And if it, or they, should reappear a day, a week, a month, or years later, with no explanation and no memory of what has taken place in the interim, what then? This couldn't possibly happen, could it? Isn't it the stuff of fantasy and fairy tales?

In fact, just such a scenario applies to one of the most famous works of Australian fiction, namely Picnic at Hanging Rock by Joan Lindsay (1896-1984). Written during the southern winter of 1966, it was published at the end of the following year, and launched in Melbourne by the former Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies. Some contemporary advertisements wrongly listed it under the biography category, and its precise status remains controversial. Though met with positive reviews upon initial publication, the book was slow to sell until a cinematic adaptation was released in 1975. Thereafter sales soared, apparently reaching 11 million copies, or readers, worldwide by 1993, with assistance from movie tie-ins, radio serialisation, hardback and paperback releases, and an Australian illustrated edition (Bushell 1993). At present it remains 'in print', alongside ebook and audiobook editions. Stage versions have appeared, alongside an Italian ballet in 2012, a BBC radio play, and a contemporary film set on a beach with similar themes (Shamas 1988, Wright 2015, Wright 2017). The online presence in the new millennium is significant, through social media outlets such as YouTube, Instagram and streaming services, all of which provide access to, and commentary on, Picnic at Hanging Rock in all its manifestations. During 2023 a restored edition, of both the original 116 minute version and the later, shortened, director's cut of 104 minutes, was issued on the high quality 4K digital format. The story lives on, both in physical forms, and the conscious mind of many.

Following the publication of the book at the end of 1967, Lindsay encountered unwanted fame, leading to a seemingly never-ending barrage of questions concerning the mysterious disappearances, and its possible historical basis. The reason for this is the fact that Picnic at Hanging Rock was skillfully presented by the author within the first chapter as a chronicle, the dictionary definition of which is a factual written account of important or historical events in the order of their occurrence. In this case it concerned three schoolgirls and a teacher who mysteriously disappear whilst on an excursion to a local geological landmark and picnic site in regional Victoria, Australia - the ominous and ever mysterious Hanging Rock.

|

| Hanging Rock @ sunset. |

Of the original four, three are never seen again, and no evidence ever found, or presented by the author in the book as originally published, which points to their true fate. Readers are faced with an unsolved, and seemingly unsolvable, mystery - a decision which to some degree Lindsay came to regret, but was never publically apologetic about. The origins of Lindsay's dilemma in creating the work and living with the consequences are just as mysterious as that of the fictional disappearances at Hanging Rock, and of the location itself. Individuals, in real life and over time, use or have used numerous terms to try to describe the strange, often malevolent feelings they encounter there. But their origin remains inexplicable, at least if a simple, scientific explanation is sought. One in the mystical, paranormal realm is usually cast aside rather offhandedly. However, within the book's deleted final chapter, Joan Lindsay provides a possible, if partial, answer. To appreciate that answer, we need to step back in time, back to the beginning of the Rock itself.

---------------------

2. The Rock - Origins, ancient & modern

Geologically speaking, Hanging Rock is a 105 metre high mamelon formation composed of trachyte - rock formed as a result of a volcanic eruption which took place some 6.25 million years ago. Science has also identified a strange magnetic field present in and around the formation, related to its distinct geology and placement within the landscape (Wilkes 2018).

As with many similar geographical features and mountainous areas across the country, Hanging Rock is of special significance to the local Aboriginal people - the Wurundjeri - who, as part of Australia's First Nations people, have inhabited the continent for more than 130,000 years, at least according to recent scientific data. Specific archaeological information from the region goes back some 26,000 years. In fact, the Dreamtime tells us that Aboriginal people have been present in Australia since time immemorial, as part of the evolution of humankind. This is likely true, though it may be eons before science is able to provide supportive evidence. It has already noted the existence of humanoid species 1.1 million years ago in the nearby Indonesian archipelago.

Hanging Rock provided local First Nations peoples with a readily identifiable landmark on an otherwise flattish landscape, in a similar vein to the more famous Uluru (Ayres Rock) of Central Australia. It was traditionally utilized for meetings, story-telling, and ceremonies such as corroborees and male initiation, with the last of the latter said to have taken place in 1851 (Cahill 2017). The Rock has long been a significant element of local Indigenous peoples' relationship with Country.

|

| Dryden's Rock near Mount Macedon, The Illustrated Melbourne Post, 25 January 1865 / Illustrated Sydney News, 16 February 1867 / Australian Town and Country Journal, 27 November 1875. |

Most of these cultural events were apparently carried out on its lower, forested sections and around the base. The upper part, distinguished by rugged, weather-worn, round-tipped, volcanic monoliths - a variant on the hexagonal basalt columns of Ireland's more ancient Giant's Causeway - was a place of spirits and dark "unfinished business" which saw the local Aborigines and visitors generally shy away from sections of it, especially during the hours between sunset and sunrise (McCulloch 2018b). Post-invasion (1788) events resulted in the decimation of local Indigenous populations and the loss of much of the cultural heritage associated with the site. Hanging Rock's ongoing status, including its desecration as an Aboriginal sacred site, was addressed in a 2017 article, which also made reference to Joan Lindsay's work:

Hanging Rock itself was a dividing point for four Aboriginal territories .... it sits at the very centre of historically and culturally valuable Indigenous land. Nor is it recognised that the outcrop held such a degree of power to the local people – established tribes who had lived in the area for more than 26,000 years – that they refused to climb it. And, perhaps predictably, it is almost never acknowledged as a site of atrocities committed by white settlers, with introduced diseases such as smallpox ravaging the local population... That [Hanging Rock] has been so desecrated by a book routinely described as one of Australia’s best isn’t some minor fib – it is one tragedy among many, all of them obscured by a weepy schoolgirl named Miranda and her waif-like, wearisome friends. (Earp 2017)

Whilst the author therein criticises the impact of Lindsay's book on local Aboriginal cultural heritage, no information is provided to address the issue of why an eeriness is present, and almost invariably encountered, by Indigenous and non-Indigenous visitors. Another author recently identified the lack of traditional stories about Hanging Rock, despite being associated over an extensive period with three tribal groups - the Woi Wurrung (Wurundjeri), the Dja Dja Wurrung and the Taungurung (Roe 2022). This loss of traditional story-telling regarding the Mount Macedon and Hanging Rock region is regrettable, resulting as it does from the decimation of the local tribes following the previously noted British invasion of 1788.

|

| Mount Macedon, Woodend and Hanging Rock landscape, oriented with north facing east. Source: Google Maps, 2 August 2023. |

In 1837 Hanging Rock was named Mount Diogenes by the colonial Surveyor General T.L. Mitchell, as he travelled from Melbourne to Sydney. A subsequent newspaper report of the journey reported the following in regard to the nearby Mount Macedon which was located just 8 kilometres south of Hanging Rock:

A trusted member of [Major T.L. Mitchell's] party was a Parramatta black named "Piper," the only one, it is said, who ascended Mount Macedon. From my knowledge of the Aboriginals, I expect Piper went and had a good sleep in the bush and then returned and told the Major fairy tales. (The Vagabond 1893)

Within this rather sarcastic comment are to be found some significant references. We know that Mitchell was interested in Indigenous "fairy tales", also known to the British by terms such as myths and legends and now often revealed as significant Dreaming stories. He recorded a number in his note books, some of which later saw it through to publication. Mitchell was also interested in local languages and allocated Indigenous names to many prominent geographical landmarks and features, such as the Murrumbidgee river. He used Greek and English terms as well, resulting in the Diogenes reference for the mount, named after the famous philosopher. It is intriguing to consider whether Mitchell recorded any stories told to Piper by the local people relating to the Mount Macedon and Hanging Rock area during his brief visit in 1837. As noted above, no such stories have subsequently been made public.

Part of the land around Hanging Rock was occupied in 1837 by Edward Dryden, who was later, along with others such as William Adams, granted title. Of course, no recognition or consideration of Aboriginal title, ownership or prior possession was given by the invaders (Gill 2013). By the 1860s, following the near complete disappearance of the local Indigenous population, Hanging Rock had become a popular picnic spot - a picturesque oasis amidst the sparse, dry landscape of the Australian bush. As a result, it thereafter passed into government ownership during 1884 and was made a public reserve.

The strange, ominous, mystical aspect of Hanging Rock encountered by the European settlers, and Indigenous people before them, has never been explained. Its presence is reflected in two engravings from 1855-56 featuring the monolithic rocks on the sides and top of the mountain.

|

| Foot of Diogenes Monument: 4 miles N. from Mount Macedon, 40 miles N.N.W. from Melbourne. Source: Blandowski 1855. |

This first dramatic image (illustrated above) features three Easter Island head-like monoliths with an electrical thunderstorm in the background and a cowering native in the foreground. The second image (illustrated below) is figured to look like a group of hooded acolytes attending a secret ceremony under the light of the full moon.

|

| W. v. Blandowski, Australia, Diogenes Monument / Anneyelong looking sth towards Mount Macedon. Effect & engraving by J. Redaway & Sons, Melbourne, 1855-56. Collection: State Library of Victoria. |

The artist responsible for both, William Blandowski, described the site in The Age Melbourne newspaper on 14 September 1855. Upon closer observation, we can see that he included in the second work a group of Aborigines camped on the side of the mountain, just below its upper reaches and by a large burning fire. They look up towards the full moon, naked and insignificant amidst the imposing geology.

|

| A group of Aborigines dance by a campfire under the light of the full moon. |

Variously known as Dryden's Rock or Monument, and Diogenes Monument or Mount upon being surveyed and named by Robert Hoddle during 1843-44, from the 1850s it was popularly referred to as Hanging Rock. The traditional name in the Aboriginal language, as recorded by Blandowski, reflects the darker aspects of the location:

The Aboriginal word gula refers to a thing (something, somewhere, or someone) malevolent, deadly, treacherous, angry or involving sorcery (Illert 2021, Organ 2022b). This, of course, is relevant to the fictional and actual mystery surrounding Hanging Rock, as these elements tie in with aspects of reality that are not part of our everyday environment, such as ghosts, godly spirits, and creatures belonging to the faërie realm.

Extra-dimensional beings in a variety of forms, long considered real and present by sections of the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities alike, can obviously inhabit physical spaces side by side, and Hanging Rock is likely one such example. The earthly faërie realm is very much associated with the natural environment and specific places such as forests and mountains which are untouched or generally isolated from human habitation, especially where the latter is dense and dangerous for faërie folk.

|

| Conrad Martens, Mount Coolangatta, 1860. |

An explanation for the presence of a non-faërie, ghostly element at Hanging Rock lies in the Aboriginal belief in an afterlife. For example, Mount Coolangatta, a similar geological feature located on the coast in New South Wales, north of Victoria, serves as a physical and mythological stairway to heaven, whereby it is believed by First Nations people that spirits of the dead travel to the top of the mountain and, upon stepping off a large stone slab there, pass on to the Indigenous equivalent of heaven, purgatory or hell (Organ 1990).

As a place of intersection between different dimensions, or realms, this seems similar to Hanging Rock, where numerous accounts over an extended period of time have spoken of a heaviness and darkness associated with the place. That otherworldly and sometimes malevolent aspect existed through to the arrival of the British in 1788, and beyond. For example, during 2023 the artist / activist and Punk Outsider Toby Zoates relayed to the present author his own eerie encounter with Hanging Rock in 1962:

I got myself lost at Hanging Rock when I was about 12, in 1962. Seriously, I shat my pants, those caves are eerie. They used to hold Easter horse races below the rocks and my parents were crazy for it. I went exploring the rocks and got lost for several hours. I actually tried to climb down the sheer rock face in an attempt at escape but gave up after about 7 ft down, as I surely would have fallen and died. I totally freaked out, felt ancient spirits haunting me, and cried my heart out. The spirits finally relented and led me through the labyrinth into the sunlight and freedom. To this day I recall the terror and spookiness. (Zoates 2023)

----------------------

3. Joan's story

Continuing through to the present, a malevolence and otherworldly aspect remains at Hanging Rock. This is undoubtedly one of the reasons Joan Lindsay was moved to write Picnic at Hanging Rock, and why she had been drawn there since her first visit during the summer of late 1899 and early 1900, and the following year again, when aged just three, going on four. One summary of the book as published reveals the mystical aspect of the location:

A party of schoolgirls goes on a picnic on St Valentine's Day, 1900. Four of them [Edith, Miranda, Marion and Irma] leave the group to explore the Hanging Rock. One of the school mistresses [mathematics teacher Miss Greta McCraw] also wanders off after them. When they do not return in time, a search is organised. The youngest girl [Edith] emerges from the hillside in hysterics, but can recall almost nothing. Of the other three girls and the mistress there is no trace. A week later, one of the girls [Irma] is found on the Rock with a few cuts and bruises on her hands and face, but her bare feet unmarked and no memory of where she has been (Lindsay, Taylor & Rousseau 1987).

It should be noted that Lindsay's chronology throughout the book indicates events took place during 1900. For example, St Valentine's Day is given as Saturday, 14 February 1900. However, it was actually Wednesday that year. The timeline throughout the book is correct for the year 1903. This may have been an accident on the part of the author, or done purposefully, though for what reason is not known. Perhaps it ties in with Lindsay's disregard for the traditional aspects of time that modern society adhere to. Or she may simply have wanted Friday to fall on the 13th of February, to tie in with the traditionally dark, mystical aspects of that day.

Picnic at Hanging Rock was written in a frenzy over a single week sometime during the southern winter (?July-August) of 1966, in close association with a series of connected, lucid dreams and sleepless nights for Joan Lindsay. We have a number of first- and second-hand accounts of the writing process. One is by the director of the 1975 film, Peter Weir:

I think I did say at some time that I thought that Lady Lindsay had been somewhat possessed when she wrote this, just from what she told me, when she sat down and it just poured out. (Peter Weir 2004)

At the time of writing she would keep her housekeeper Rae updated on its progress:

She really did dream the sequence of chapters ..... (McCulloch 2017b)

The author herself recorded a number of accounts, with minor variations between them:

Well now, Picnic at Hanging Rock really was an experience to write, because I was just impossible when I was writing it. I know. I just sort of thought about it all night long. I think a great many writers, I understand, I think Patrick White was the same, not that I'm comparing myself to him, but I think a lot of them lay awake at night and think about what they are going to write next day. I used to write half of that book in my head. I'm talking about Picnic now. And in the morning I would go straight up to a little room upstairs, sit on the floor, papers all around me, like that, and just write like a demon, because I knew exactly what was going to happen from the night before. It was almost as if it was before me in a kind of, it was almost like a film. When I wrote it I wasn't thinking of a film, but it was a very visual experience for me.... [As regards the mystery] I can only say for me, fact and fiction are so closely allied, some of it really happened and some of it didn't. And to me it all happened; it was all terribly true for me. (Joan Lindsay 1974)

I just saw it all passing before my eyes, usually lying in bed at night. When I woke up in the morning I knew exactly what the next bit was going to be. I never had any trouble about what was going to happen. I just knew. (Joan Lindsay 2004)

Lindsay was almost seventy at the time of writing Picnic at Hanging Rock, and stated in the draft of the book's Foreward that the narrative was based on an actual event, or events, though with a caveat:

Foreward. Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is Fact or Fiction, or both, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are now long since dead, it hardly seems important, seeing that we live in an age when Fact is often harder to swallow than Fiction. (Lindsay 1967, McCulloch 2017 a & b)

She also provided, within the published chapter 17 - therein the final chapter - what was claimed to be evidence in the form of a newspaper report from 1913. However, none of this was true. Well, that's not entirely true either, for the book, despite supposedly being a work of pure fiction, is based not only on the real and truthful experience of the aforementioned dreams, but also, and more loosely, around events which took place during the life of the author, or were otherwise historic. For example, we know the following:

- Miss McCraw of the book was based on an actual teacher by that name, as were Marion, Mr Hussey and Doctor Mackenzie based on real people;

- The school picnic at Hanging Rock was based on events connected with Lindsay's own schooling, though she did not apparently participate in such an event;

- Lindsay visited Hanging Rock on a number of occasions with her family during her childhood and later;

- The mysterious disappearance, and sometime reappearance, of children in the bush did occur in Victoria during the nineteenth century, most famously in the case of Clara Crosbie / Crosby who went missing for two weeks during 1885;

- Lindsay had psychic abilities and was referred to as a mystic by her friends, including film director Peter Weir;

- Lindsay believed in, and experienced, the concept of time as fluid - she saw part, present and future events;

- Lindsay was precognitive, frequently experiencing premonitions;

- Clocks, wrist watches and machines stopped in Lindsay's presence;

- Lindsay could see things (faërie?) that other people could not see, especially in the bush landscape, and including figures dressed in black at night;

- Lindsay could communicate with beings, creatures and things that were not of the earthly dimension;

- The 'fictional' account of a more mystical nature included in the original manuscript, and in which individuals had encounters with strange creatures or spirits, seen and unseen, did take place, both in fact and fiction;

- During a visit to Hanging Rock with her friend Colin Caldwell in 1963, half way up he left her alone, to, as he later recalled, .... feel that haunted thing... She always had rather unusual abilities and could sense things in the landscape that others couldn't....

- Lindsay's biographer noted: It was clear that Lindsay was interested in Spiritualism, and longed for some spiritual dimension in her life....

- Lindsay told artist Martin Sharp that she had ... an experience on Hanging Rock when she was a very young girl and that it had profoundly affected her (Edward 2017). The specific nature of the experience is not known, but can be assumed to relate in some way to what is presented in the book.

All of this lies at the heart of the problem with Picnic at Hanging Rock - it is a frustratingly unsolved mystery and, at the same time, a consummate amalgamation of fact and fiction by a skilled writer, much as so many others have done, based on real events and events that never happened, but could have, and perhaps even did. J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings is a perfect example of a similar fantasy fiction grounded in historical, and mythological / faërie reality, with his Elves being the most obvious inclusion. Written between 1937-48 in what that author said was largely an unconscious process - as though he was just the mere instrument of some unknown intelligence - it can also be seen to be based on actual incidences in Tolkien's life, such as his military service during World War I, on previously published mythologies from Great Britain and Europe, and on historical events, all presented in a totally new and believable, though medieval context - a secondary world, as his son Christopher put it. It was fantasy fiction at its finest. Picnic at Hanging Rock is also that, arising in part out of the subconscious, lucid dreaming of Australian Joan Lindsay. It is a dream within a dream, to quote Edgar Allan Poe, the American poet and Gothic mystery writer.

Like Tolkien's masterwork, Picnic at Hanging Rock was subsequently made into an internationally successful feature film. Directed by Peter Weir, and released in 1975, he was aware of this element, and opened his film with that precise phrase from Poe's poem:

What we see and what we seem are but a dream - a dream within a dream (Poe 1850 / Green 1975).

The placement of those words at that point was utilised by the director to open a doorway for the viewer to step through into a realm which, though it may have felt real and historic, was also of a different, dream-like dimension. The movie version of Picnic at Hanging Rock provided its audience with a beautiful, sensual, inexplicable experience of events directly taken from the book. It is now recognised internationally as a classic of the genre, for its skillful production and intriguing narrative, despite, or perhaps because of, the fact that it ends somewhat frustratingly in an unsolved, and seemingly unsolvable, mystery. The 2018 television series is more mystical, other worldly, not because it aimed to replicate Weir's film, but because they were features of the book to which the scriptwriter sought to adhere more closely to.

Numerous reviews and commentaries continue to appear in print and online, lauding the work in its various forms and breaking down themes and motifs presented therein, either real or perceived. One recent example is that by the deepfocuslens YouTube channel, wherein the narrator highlights the element of fear in Weir's Picnic at Hanging Rock, which she considers one of the top five international films of the 1970s. At one point she states:

There is, to me, almost nothing more terrifying than existing one moment, and then the next you're gone, and there's no explanation, no one can find you. Loved ones look and look and look, and you're just gone (deepfocuslens 2022).

Picnic at Hanging Rock - movie review, deepfocuslens, YouTube, 8 February 2022, duration: 19.17 minutes.

As in the book, the YouTuber does not explain such a disappearance or make mention of the faërie realm. Whatever the actual circumstances of the disappearance, self inflicted or malevolent, to the reader it is nevertheless tragic for those left behind, despite the societal impacts prevailing over the familial in Lindsay's narrative. For example, the author excludes any actual description, or reference to, the impact of the disappearances on the families of Miranda, Marion and Miss McCraw. The horrified and immediate reaction of Irma Leopold's parents, though distant, is clearly outlined, as is the action taken to remove her from Appleyard College post haste. Early in the book it was noted that Miranda's father had sent her a loving St. Valentine's Day card, featuring Baby Jonnie's home-grown cupid and a row of loving kisses.

|

| St Valentine's Day cards, featuring cupid, early 1900s. |

The winged cupid featuring in cards from the Edwardian era (early 1900s) is very fairy-like, though based on Eros, the male Greek god of love. Valentine's Day was always special to Joan Lindsay. In 1912 she wrote a poem entitled Your Valentine, and during 1930 published a piece of fantastical prose in which she posited St Valentine coming down to earth and being surprised that the card-based celebrations of the Edwardian era were no longer popular (Lindsay 1930, O'Neil 2009b). As a result, he took a bodily form, went into the Sydney David Jones store, and ordered a pair of silk stockings ...for a very pretty young lady with wings.

Later in the book we are informed of Mrs Appleyard's dread of receiving a response from Miranda's family in Queensland to the loss of their beloved daughter. That such a shocking, inexplicable event should lie at the heart of Picnic at Hanging Rock is intriguing, remembering that it occurs in chapter 3 of the book and the remainder is concerned with the consequences, spreading as they do, tentacle-like, out through society and even beyond time to the present day.

There are numerous characters featured in Picnic at Hanging Rock, most notably the 57 year old headmistress Mrs Appleyard, and the youngest student, 13 year old orphan Sara Waybourne. The child is subsequently murdered by Appleyard, following an extended period of physical and mental abuse. It had been varoously suggested that Sara was driven to suicide as a result of an unrequited love for Miranda. However, a close reading of what Lindsay wrote reveals this to be false. It is rejected in light of Appleyard's lie to Mademoiselle de Poitiers about Sara's disappearance (i.e., that she was secreted away by her guardian) and her own subsequent suicide by jumping off Hanging Rock upon the realisation that her action was about to be found out by both the police and Sara's guardian.

In the following discussion we are only concerned with the fate of the five involved in the disappearance, and specifically the three who never return:

- Miranda - an Appleyard College senior, its most popular student, and perhaps most beautiful, being a tall pale girl with straight yellow hair, aged 18. She leads the group up Hanging Rock and remains lost.

- Marion Quade - the cleverest student, aged 17. Remains lost.

- Irma Leopold - the wealthiest student, small and with black, curly hair, also 17. Found by Michael and Albert on Hanging Rock a week after disappearing.

- Edith Horton - the youngest student, plump, aged 14. She is the first to leave the group heading up Hanging Rock, heavily traumatised and screaming for an unknown reason.

- Miss Greta McCraw - an "old maid" aged 45, mathematics teacher at the college. Apparently transforms into a crab-like creature and remains lost.

|

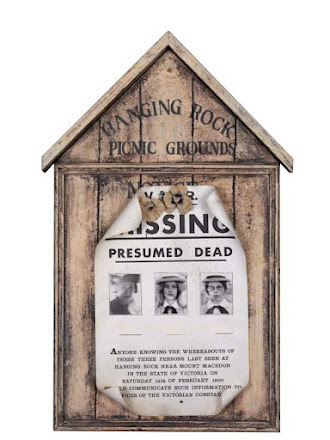

| Missing - Presumed Dead, poster and notice board prop from Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975). Collection: National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra. |

Due in large part to the success of the film, the idea of the supposed factual nature of the disappearance of the schoolgirls and their teacher has become an entrenched part of Australian folklore. To this day the question is asked, especially by Victorians: What is the truth behind the mystery of Hanging Rock? What happened to the schoolgirls? Such questions are posed as though there remains an actual murder mystery, rather than arising from a mere work of fantasy fiction, or fairy tale. This is due to the skill of Lindsay in portraying the period, presenting the events, and defining the characters, and of course to Peter Weir and his team in bringing it all to public notice through the 1975 cinematic version. A six-part television series retelling the story in greater detail, and released in 2018, reinforced the emphasis on mystery previously created by Lindsay and Weir, though included more of the mystical aspects contained within the text. This latter version is discussed further below.

-------------------------

|

| Fred McCubbin, The Lost Child, 1886, National Gallery of Victoria. |

4. The truth of the disappearance

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world's more full of weeping

than you can understand.

(The Stolen Child, W.B. Yeats 1886)

'Don't worry about us, Mam'selle dear,' smiled Miranda. 'We shall only be gone a very little while.' .....

Why do we have to understand everything? There are mysterious things that will never have a proper, factual explanation..... (Joan Lindsay)

In 1967 the original ending (chapter 18) of Picnic at Hanging Rock, which partially explained the disappearance of the schoolgirls and teacher, was deleted from the manuscript by the publishers, on the advice of junior editor Sandra Forbes. Apparently the publisher eventually garnered the support of Joan Lindsay in the decision, though later events would suggest this was begrudgingly given at the time and later pulled back. Why the deletion? Because, in the opinion of the present author, that chapter delved into the mystical, and little understood locally, faërie realm, a dimension where space and time is not as we know it. Within the deleted chapter Lindsay refers to it as a plane of common experience, wherein the three schoolgirls are drawn together with Miss McCraw's changeling, or doppelganger.

That chapter, and by extension the entire work, was in hindsight, and in many ways, of its time - 1966 - trippy .... like a group of people under the influence of a powerful hallucinogen (Wargo 2018). Whilst Lindsay may have been tuned into the prevailing zeitgeist, just as Lewis Carroll had a century before whilst part of the radical Pre-Raphaelite movement, those at Cheshire Publishing certainly were not (Carroll 1865). They included publisher Frank Cheshire, publishing director Frank Fabyini, senior editor John Hooker and junior editor Sandra Forbes. The latter write of seeking to enhance the ambiguity of the original manuscript. They were obviously not enamored of the paranormal and faërie aspects of Lindsay's work, and sought to diminish and editorially censor it. But what exactly is faërie and the faërie realm?

Faërie is an English term referring to mythical or real creatures, elementals, and sentient beings that may have supernatural powers and usually occupy a dimension not aligned with the human reality but, at times, overlapping. It is most commonly known through the use of the word fairy, which is just one element of it. The dimension inhabited by faerie is referred to as the faërie realm. Encounters can be short or long, multidimensional, serendipitous or planned on the part of faërie or human kind, fruitful or frightening, and incidental or fateful, as in the case of Lindsay's novel. They, or rather it (faërie), largely exist in the fantasy genre between fiction and reality, usually presented therein under the umbrella term folklore and often pitched towards juvenile audiences, though not always, with Gothic horror being an example of the latter. The presence of faërie in reality has in recent times garnered greater acceptance (Organ 2023).

During the first half of 1967, those involved in the publication of Picnic at Hanging Rock came to the conclusion that inclusion of Lindsay's final chapter would diminish the traditionally conservative, mystery aspect of the book, and thereby impact upon sales. Whilst probably correct in regards to the latter, the decision was nevertheless regrettable, to say the least, as it removed the story's climactic ending wherein many of the early threads were drawn together. The mystery element would still have been there if it had been left in, and the chapter would have added significantly to the mystical aspect of the work. The decision to delete, or censor, reinforced, and revealed, the local antipathy towards faërie and the unexplained. Yet this had long been part of Australia's colonial literary heritage, as imported from Great Britain upon the arrival of the First Fleet back in 1788 and taught in schools through to the twentieth century. This is discussed in the present author's Faërie in Australia.

Picnic at Hanging Rock was part of a new wave of indigenous literature which was set in the Australian bush and often, though not in this particular instance, specifically incorporated aspects of Indigenous mythology and story telling, though some Post-Modernists would suggest otherwise (Earp 2017, Spiers 2017). In addition, Weir's later film was a landmark in a new era of Australian culture expression, facilitated by the election of the Whitlam Labor government in 1972, and the support therein for the local arts establishment, rather than ongoing reliance of English and American content. This renaissance took place in the wake of almost two centuries of anglophilia, and the reactionary, countercultural revolution which had taken place across Western societies during the 1960s and early 1970s, arriving somewhat late in Australia. Just as censorship of literary texts was railed against in Australia during the 1960s, largely based on sexual and political content, so Lindsay came to regret its application to Picnic at Hanging Rock in 1967. Precise reasons were not given, though tone and style were apparently some of those suggested, along with the ambiguity issue.

During 1972 Lindsay passed a copy of the expunged chapter on to her literary agent John Taylor. She then allocated him copyright during 1980, with the caveat that it should be published upon her death. In its absence, the question of the mystery of Hanging Rock became a popular conversation topic, especially during and after release of the film in 1975. As a result, a book was published in 1980 by Veronique Rousseau presenting four possible solutions to the mysterious disappearances presented in Picnic at Hanging Rock. It was based on a precise reading of the text and comments by the original author (Rousseau 1980). Some of the information uncovered as part of that research is included in a section below dealing with historical research into the disappearances outlined in the book.

Following Lindsay's death at the end of 1984, the unpublished chapter 18 was published in booklet form during 1987. It partially revealed what happened after the disappearance, whilst providing additional, though intriguing context to that event. The full text is reproduced below.

-------------------------

5. The Secret of Hanging Rock (1966 / 1987)

The missing chapter 18 .... is one of the most fascinating and beautiful pieces of “paranormal fiction” I have ever read. (Wargo 2018)

The following text, known as Chapter 18, is from Joan Lindsay's original draft manuscript for Picnic at Hanging Rock, written during 1966. It was subsequently excluded from the published version, on the advice of, amongst others, the Cheshire Publishing junior editor Sandra Forbes. As a result, Lindsay was forced to incorporate a few elements from her original chapter 18 into chapter 3 of the book, mainly in connection with the lead up to the disappearances. That amended and edited version was published at the end of 1967.

The text of chapter 18, as publically revealed in 1987, differs slightly in style from the 1967 text as it is an earlier, unedited copy of the typed draft manuscript. As such, it had not been polished or tightened up by Forbes' editing, whereby elements such as a consistent voice would have been applied, typographical errors corrected, and formatting standardised in line with the rest of the text. For example, the following text appears in chapter 18 of the original manuscript:

At last the bushes are thinning out before the face of a little cliff that holds the last light of the sun. So, on a million summer evenings, the pattern forms and re-forms upon the crags and pinnacles of the Hanging Rock.

It takes the following form in chapter 3 of the 1967 publication, with a change in tense and slightly different wording:

Until at last the bushes began thinning out before the face of a little cliff that held the last light of the sun. So on a million summer evenings would the shadows lengthen upon the crags and pinnacles of the Hanging Rock.

In discussing these edits, McCulloch felt they were disjointed, and the lines appeared to make no sense (McCulloch 2018b). In fact, and in the view of the present author, they add clarity to certain events, such as the two instances when the girls look down from the top of Hanging Rock and, initially see their fellow students and teacher. On the second occasion, and unknown to them, they observe a search party. In order to clarify this chronological discrepancy and slip in time, the present author has elsewhere combined chapters 3 and 18 into a single chapter which, when read in conjunction with the rest of the book, ensures that the chronological flow of events on the afternoon of St. Valentine's Day is maintained. McCulloch also refers to a whole page of the original draft manuscript - a complete copy of which survives - that was omitted, dealing with an event which took place while the students and teachers were on route to Hanging Rock. She quotes the following extract:

They were within half a mile or so of the Picnic Grounds when there was an abrupt cessation of the easy jolting pace of the drag [passenger coach], together with a sensation of breaking and slipping, rather like a clock quietly ticking on the mantlepiece that suddenly runs down. The two sisters from New Zealand, remembering the awful stillness of the moment before an earthquake, trembled and clung. From the interior of the vehicle, grown unaccountably dark, Greta McCraw uttered a jubilant croak (Lindsay in McCulloch 2018b).

The significance of that text is related to the idea of a changeling version of Miss McCraw being present in the coach with the schoolgirls, rather than the real Miss McCraw. Changelings are shape-shifters, used by faërie in kidnapping or enticing children and young people away from family (Whalen 2023). They can take any form, and their transformation is not permanent.

Due to lack of clarity in regards to some of the conversations which appear in the original draft chapter 18 as published in 1987, and who is the speaker therein, the current author has inserted indicators where such is ambiguous, especially in regard to the 'stranger', who is the faërie form (a changeling or doppelganger) of Miss McCraw. Also, texts highlighted in bold below were subsequently inserted by Lindsay into chapter 3, prior to publication in the 1967. Chapter 18 opens with a paragraph outlining how the events described take place in a never-ending, timeless place - the unnamed faërie realm - from which the participants do not, or cannot, escape.

Chapter 18

It is happening now. As it has been happening ever since Edith Horton ran stumbling and screaming towards the plain. As it will go on happening until the end of time. The scene is never varied by so much as the falling of a leaf or the flight of a bird. To the four people on the Rock it is always acted out in the tepid twilight of a present without a past. Their joys and agonies are forever new.

Miranda is a little ahead of Irma and Marion as they push on through the dogwoods, her straight yellow hair swinging loose as corn silk about her thrusting shoulders. Like a swimmer, cleaving wave after wave of dusty green. An eagle hovering in the zenith sees an unaccustomed stirring of lighter patches amongst the scrub below, and takes off for higher, purer airs. At last the bushes are thinning out before the face of a little cliff that holds the last light of the sun. So, on a million summer evenings, the pattern forms and re-forms upon the crags and pinnacles of the Hanging Rock.

The plateau on which they presently emerged from the scrub had much the same conformation as the one lower down - boulders, loose stones, an occasional stunted tree. Clumps of rubbery ferns stirred faintly in the pale light. The plain below was infinitely vague and distant. Peering down between the ringing boulders, they could just make out tiny figures coming and going, through drifts of rosy smoke. A dark shape that might have been a vehicle beside the glint of water.

"Whatever can those people be doing down there, scuttling about like a lot of busy little ants?"

Marion came and looked over Irma's shoulder.

"A surprising number of human beings are without purpose." Irma giggled. "I dare say they think themselves quite important."

The ants and their fires were dismissed without further comment. Although Irma was aware, for a little while, of a rather curious sound coming up from the plain, like the beating of far-off drums.

Miranda had been the first to see the monolith - a single outcrop of stone something like a monstrous egg, rising smoothly out of the rocks ahead above a precipitous drop to the plain.

Irma, a few feet behind the other two, saw them suddenly halt, swaying a little, with heads bent and hands pressed to their breasts as if to steady themselves against a gale.

[Irma] "What is it, Marion? Is anything the matter?"

Marion's eyes were fixed and brilliant, her nostrils dilated, and Irma thought vaguely how like a greyhound she was.

[Marion] "Irma! Don't you feel it?"

"Feel what, Marion?" Not a twig was stirring on the little dried-up trees.

"The monolith. Pulling, like a tide. It's just about pulling me inside out, if you want to know."

As Marion Quade seldom joked, Irma was afraid to smile. Especially as Miranda was calling back over her shoulder, "'What side do you feel it strongest, Marion?"

"I can't make it out. We seem to be spiralling on the surface of a cone - all directions at once."

Mathematics again! When Marion Quade was particularly silly it was usually something to do with sums.

Irma said lightly, "sounds to me more like a circus! Come on, girls - we don't want to stand staring at that great thing forever."

As soon as the monolith was passed and out of sight, all three were overcome by an overpowering drowsiness. Lying down in a row on the smooth floor of a little plateau, they fell into a sleep so deep that a lizard darted out from under a rock and lay without fear in the hollow of Marion's outflung arm, while several beetles in bronze armour made a leisurely tour of Miranda's yellow head.

Miranda awoke first, to a colourless twilight in which every detail was intensified, every object clearly defined and separate. A forsaken nest wedged in the fork of a long-dead tree, with every straw and feather intricately laced and woven; Marion's torn muslin skirts fluted like a shell; Irma's dark ringlets standing away from her face in exquisite wiry confusion, the eyelashes drawn in bold sweeps on the cheek-bones. Everything, if you could only see it clearly enough, like this, is beautiful and complete. Everything has its own perfection.

A little brown snake dragging its scaly body across the gravel made a sound like wind passing over the ground. The whole air was clamorous with microscopic life.

Irma and Marion were still asleep. Miranda could hear the separate beating of their two hearts, like two little drums, each at a different tempo. And in the undergrowth beyond the clearing a crackling and snapping of twigs where a living creature moved unseen towards them through the scrub. It drew nearer, the crunchings and cracklings split the silence as the bushes were pushed violently apart and a heavy object was propelled from the undergrowth almost on to Miranda's lap.

It was a woman with a gaunt, raddled face trimmed with bushy black eyebrows - a clown-like figure dressed in a torn calico camisole and long calico drawers frilled below the knees of two stick-like legs, feebly kicking out in black lace-up boots.

[Stranger] "Through!" gasped the wide-open mouth, and again, "Through!"

The tousled head fell sideways, the hooded eyes closed.

"Poor thing! She looks ill," Irma said. "Where does she come from?"

"Put your arm under her head," Miranda said, "while I unlace her stays."

Freed from the confining husks, with her head pillowed on a folded petticoat, the stranger's breath became regular, the strained expression left her face and presently she rolled over on the rock and slept.

"Why don't we all get out of these absurd garments?" Marion asked. "After all, we have plenty of ribs to keep us vertical."

No sooner were the four pairs of corsets discarded on the stones and a delightful coolness and freedom set in, than Marion's sense of order was affronted.

"Everything in the universe has its appointed place, beginning with the plants. Yes, Irma, I meant it. You needn't giggle. Even our corsets on the Hanging Rock."

"Well, you won't find a wardrobe," Irma said, "however hard you look. Where can we put them?"

Miranda suggested throwing them over the precipice. "Give them to me."

"Which way did they fall?" Marion wanted to know. "I was standing right beside you but I couldn't tell."

[Stranger] "You didn't see them fall because they didn't fall."

The precise croaking voice came at them like a trumpet from the mouth of the clown-woman on the rock, now sitting up and looking perfectly comfortable.

[Stranger] "I think, girl, that if you turn your head to the right and look about level with your waist . . ."

They all turned their heads to the right and there, sure enough, were the corsets, becalmed on the windless air like a fleet of little ships. Miranda had picked up a dead branch, long enough to reach them, and was lashing out at the stupid things seemingly glued to the background of grey air.

"Let me try!" Marion said. Whack! Whack! "They must be stuck fast in something I can't see."

"If you want my opinion," croaked the stranger, "they are stuck fast in time. You with the curls - what are you staring at?"

[Irma] "I didn't mean to stare. Only when you said that about time I had such a funny feeling I had met you somewhere. A long time ago."

[Stranger] "Anything is possible, unless it is proved impossible. And sometimes even then." The scratchy voice had a convincing ring of authority. "And now, since we seem to be thrown together on a plane of common experience - I have no idea why - may I have your names? I have apparently left my own particular label somewhere over there." She waved towards the blank wall of scrub. "No matter. I perceive that I have discarded a good deal of clothing. However, here I am. The pressure on my physical body must have been very severe."

She passed a hand over her eyes and Marion asked with a strange humility, "Do you suggest we should go on before the light fades?"

[Stranger] "For a person of your intelligence - I can see your brain quite distinctly - you are not very observant. Since there are no shadows here, the light too is unchanging."

Irma was looking worried. "I don't understand. Please, does that mean that if there are caves, they are filled with light or darkness? I am terrified of bats."

Miranda was radiant. "Irma, darling - don't you see? It means we arrive in the light!"

"Arrive? But Miranda .... where are we going?"

[Stranger] "The girl Miranda is correct. I can see her heart, and it is full of understanding. Every living creature is due to arrive somewhere. If I know nothing else, at least I know that."

She had risen to her feet, and for a moment they thought she looked almost beautiful.

[Marion] "Actually, I think we are arriving. Now."

A sudden giddiness set her [Marion] whole being spinning like a top. It passed, and she saw the hole ahead. It wasn't a hole in the rocks, not a hole in the ground. It was a hole in space. About the size of a fully rounded summer moon, coming and going. She saw it as painters and sculptors saw a hole, as a thing in itself, giving shape and significance to other shapes. As a presence, not an absence - a concrete affirmation of truth. She felt that she could go on looking at it forever in wonder and delight, from above, from below, from the other side. It was as solid as the globe, as transparent as an air-bubble. An opening, easily passed through, and yet not concave at all. She had passed a lifetime asking questions and now they were answered, simply by looking at the hole. It faded out, and at last she was at peace.

The little brown snake had appeared again and was lying beside a crack that ran off somewhere underneath the lower of two enormous boulders balancing one on top of the other. When Miranda bent down and touched its exquisitely patterned scales it slithered away into a tangle of giant vines.

Marion knelt down beside her and together they began tearing away the loose gravel and the tangled cables of the vine.

[Marion] "It went down there. Look, Miranda - down that opening." A hole - perhaps the lip of a cave or tunnel, rimmed with bruised, heart-shaped leaves.

[Stranger] "You'll agree it's my privilege to enter first?"

[Miranda & Marion] "To enter?" they said, looking from the narrow lip of the cave to the wide, angular hips.

[Stranger] "Quite simple. You are thinking in terms of linear measurements, girl Marion. When I give you the signal - probably a tap on the rock - you may follow me, and the girl Miranda can follow you. Is that clearly understood?" The raddled face was radiant.

Before anyone could answer, the long-boned torso was flattening itself out on the ground beside the hole, deliberately forming itself to the needs of a creature created to creep and burrow under the earth. The thin arms, crossed behind the head with its bright staring eyes, became the pincers of a giant crab that inhabits mud-caked billabongs. Slowly the body dragged itself inch by inch through the hole. First the head vanished: then the shoulder-blades humped together; the frilled pantaloons, the long black sticks of the legs welded together like a tail ending in two black boots.

"I can hardly wait for the signal," Marion said. When presently a few firm raps were heard from under the rock she went in quite easily, head first, smoothing down her chemise without a backward glance.

"My turn next," Miranda said.

Irma looked at Miranda kneeling beside the hole, her bare feet embedded in vine leaves - so calm, so beautiful, so unafraid.

"Oh, Miranda, darling Miranda, don't go down there - I'm frightened. Let's go home!"

"Home? I don't understand, my little love. Why are you crying? Listen! Is that Marion tapping? I must go." Her eyes shone like stars. The tapping came again. Miranda pulled her long, lovely legs after her and was gone.

Irma sat down on a rock to wait. A procession of tiny insects was winding through a wilderness of dry moss. Where had they come from? Where were they going? Where was anyone going? Why, oh why, had Miranda thrust her bright head into a dark hole in the ground? She looked up at the colourless grey sky, at the drab, rubbery ferns, and sobbed aloud.

How long had she been staring at the lip of the cave, staring and listening for Miranda to tap on the rock? Listening and staring, staring and listening. Two or three runnels of loose sand came pattering down the lower of the two great boulders on to the flat upturned leaves of the vine as it tilted slowly forward and sank with a sickening precision directly over the hole.

Irma had flung herself down on the rocks and was tearing and beating at the gritty face of the boulder with her bare hands. She had always been clever at embroidery. They were pretty little hands, soft and white.

END

--------------------

It is dusk. Twilight casts a faint glow upon a meadow. You are walking a dirt path along the edge of a dark forest. From deep within you hear a sound, like a melding of speech and song. Something, you know not what, impels you to follow. As you enter the woods, it feels as though you've crossed a threshold. Though you had only walked a few steps, when you look back the place from whence you came is gone. There is a stillness, and a sense that the forest had fallen silent only just before you had arrived, as if it did not want to be heard. There is a secret here, protecting hallowed ground. The branches of the trees sway like a slow dance, and time seems to slow with it. How much has passed - minutes, hours? Something moves in the shadows, and the feeling creeps in that you are not alone. A pale light appears in the distance, floating towards you like a feather on the breeze, though the air is still. You have now entered the faërie realm... (Christian, The Hidden Passage, 2023)

I peered in, and there, all alone, sat an incredibly old little man with bright, blue eyes, playing away like a fairy on a home-made wooden flute (Lindsay 1934).

Whether we talk of it or not, that awful thing is always in my mind .... always and always. (Irma Leopold, 1900)

Due to the official publication of the deleted chapter in 1987, Picnic at Hanging Rock could now rightly be referred to as an ambiguous, dark, fairy tale (Gibson 2019). But what precisely had the book and additional chapter got to do with the so-called faërie realm mentioned in the title of this article - a realm which is little known or discussed in the Australian context?

Mannun, Episode 11 - The Faery Realm, Witch 'N the Working, YouTube, 2020, duration: 22.56 minutes.

The faërie realm, where it is known, is primarily associated with the sugary, happily-ever-after Disneyesque world of Tinkerbell and the Fairy Godmother. However, as noted in the videos above and below, at times the faërie realm can present a much darker and malevolent suite of characters, creatures, and tragic outcomes.

The History of Fairies - the dark & tragic stories you were never told, Mythology & Fiction Explained, YouTube, 19 March 2022, duration: 19.58 minutes.

This malevolent aspect is not only seen within Picnic at Hanging Rock but also revealed in the long tradition of child and adult abduction by faërie, on a worldwide basis, both in fantasy and reality. In the latter instance, many such events have been blamed on earthly or alien kidnappings (Blacker 1967, Cutchin 2018, Luck 2022). In fiction they are commonly stories of children being enticed away into the faërie realm utilising what is referred to as a glamour spell and, in some instances, being replaced by so-called changelings, who appear superficially identical to the stolen child or older person, similar to a doppelganger, which can be real or spirit. We observe this in the 2018 television adaptation of Picnic at Hanging Rock and the scene where Miranda is walking through the bush, along the lower slopes of the mountain, and as she looks upwards towards the monoliths she sees a second group identical to hers, disappearing in amongst the rocks. Obviously one of the groups is real, and the other is four faërie changelings or doppelgangers. This is not mentioned in the original novel, but has been developed by the program scriptwriter, Beatrix Christian, obviously in an effort to expand the mystical aspects of the television series in line with chapter 18. It ties in with the later appearance of a McCraw changeling.

The faërie elements of Picnic at Hanging Rock were substantially expanded upon in that final chapter, though they had appeared sporadically in the earlier chapters as well, and been noticed by readers such as her literary agent and former promotions manager at Cheshire Publishing, John Taylor, in 1972 when queried by the author. Lindsay had indicated a possible crossover into the faërie realm within chapter 3 of the book as published, referring to drifts of rosy smoke seen by the girls as they looked down on the plain below Hanging Rock and saw ant-like figures, along with the beating of far-off drums heard by Irma. Therein the latter was suggestive of a possible faërie event taking place, enticing the girls to join in.

The only external reference to a faërie element within the many subsequent reviews and commentaries of and on Picnic at Hanging Rock that this author has found is the following brief mention by Veronique Rousseau in connection with the publication of chapter 18:

A pink cloud (or pink smoke) is introduced to mark a boundary with physical reality; within the region of the cloud (as in legendary fairy kingdoms) time passes at a different rate ... (Lindsay, Taylor and Rousseau 1987)

Otherwise that author suggests a complex, metaphysical and time-based multidimensional realm as the ultimate fate of those who went missing. Outside of the context provided by the original chapter 18, the true significance of the cliff-top observation as a Joan Lindsay experienced time slip was not available to the reader. Both of these elements had been inserted into chapter 3 following the excision of chapter 18. Of course, that final chapter expanded upon all of this mystical material. Whether additional elements of faërie were dispersed amongst other chapters, but deleted by Sandra Forbes during the editing process, is not known.

There are some significant difference between what was incorporated into chapter 3 and appeared in the 1967 published text, and what took place during chapter 18 in regard to the ultimate disappearance of the schoolgirls and their teacher. Approximately twenty sentences or statements overlap between the two sources, where Lindsay took sections of the deleted chapter and inserted them into the final edit. For example, the earlier (1966) chapter 18 opens noting that Edith has already left the three girls, whilst in the later (1967) published chapter 3 there is an expansion of what happens whilst she is still with them. Therein Edith does not leave the group until after they have passed the monolith and been put to sleep. When the four awake, she sees the other three girls walk off and disappear, all the while screaming for Miranda to come back. She then runs off down the hill back to the picnic area. In the earlier (1966) version Edith is already gone prior to their encountering the monolith. When the three girls awake after passing it, they alone encounter the stranger, and are then present as it transforms into a partially crab-like creature.

Chapter 18 reveals that the schoolgirls and former Miss McCraw had stepped into a different dimension of reality, encountering there a Pied Piper-type figure - referred to simply as a stranger or clown-woman - who drew them deeper into that world and their ultimate, unknown destination (Masson 2016). We now find out why the Miss McCraw seen by Edith when she ran screaming down the hill was not fully clothed, and seemingly very different from the prim, proper and very staid Appleyard College mathematics teacher they knew so well. This was never explained in the 1967 book, but it is in the deleted chapter, or at least hinted at.

Throughout the book Lindsay is pointing to the Miss McCraw that Edith saw as a faërie changeling, or doppelganger. In chapter 18 the creature reveals, somewhat surprisingly, that ....the pressure on my physical body must have been very severe, causing it to disrobe along the pathway. A number of questions arise from this statement. Firstly, was the changeling herein referencing the process whereby a faërie corporeal spirit is able to create a doppelganger body as needed? It would seem that in creating the McCraw doppelganger (i.e., the changeling) the bodily features were rough - a woman with a gaunt, raddled face trimmed with bushy black eyebrows - a clown-like figure dressed in a torn calico camisole and long calico drawers frilled below the knees of two stick-like legs, feebly kicking out in black lace-up boots - and the clothing similarly haphazard. This was not the Miss McCraw that the three schoolgirls were used to, especially Marion, the ace mathematics student.

We can also ask: at what point did the real Miss McCraw disappear and be replaced by the faërie realm changeling? We can assume it occurred prior to her leaving Appleyard College on the morning of the picnic, judging by the comments made by Hussey, Mademoiselle de Poitiers and the author on the trip to Hanging Rock. This also helps explain the section in the text where, as McCraw is walking along the lower path of the track towards the summit, her footprints simply disappear. We can assume this is the point at which she enters into the faërie realm, and starts to float in a manner similar to the group of girls before her. The strangeness of the new stranger (changeling / doppelganger), and its speech, is further revealed when it informs Marion that it can see her brain (representing intelligence) and Miranda that it can see her heart (representing compassion). Both Hussey and de Poitiers comment upon the out-of-character behaviour by McCraw.

The later reference by Lindsay to the stranger's arm transforming into pincers, similar to the giant crabs which inhabit billabongs, is the closest the author gets within the book to possibly referencing Aboriginal Dreaming stories and accounts of the creature known as the Bunyip. The suggested connection therein is tentative at best, and not indicative of Lindsay applying any specific knowledge of Aboriginal mythology within the text. Also, crab-like creatures are not known to be associated with bunyips. It has been claimed by some that the crab transformation is based on aspects of the Dreamtime, but no specific evidence has been found for this (Lindsay, Taylor and Rousseau 1987). Whilst totemic associations are common within Australian First Nations society, these are sometimes associated with rebirth and reincarnation, though not with transformation as far as the present author is aware. In fact, the crab transformation is more likely associated with European faërie mythology, wherein the crab is presented as a messenger and guide. Evidence for this is provided below under The Fairy Crab section. The present author's reading of Picnic at Hanging Rock found it devoid of specific references to Indigenous mythology, with only the single mention of an Aboriginal tracker being brought into the search following the disappearance. Lindsay does not appear to be aware of any Dreamtime stories relating to Hanging Rock, and none have subsequently been revealed.

Another mystical element of the disappearance is the transformation of Miranda just prior to entering the hole, or cave in the ground. It is noted that, in the view of Irma, Miranda was radiant ... so calm, so beautiful, so unafraid.... her eyes shone like stars. This was obviously an element of the faërie enticement of Irma - the application of glamour as it pertains to enchantment and magic - which sought to have her follow the other two girls and the stranger down the hole. It did not work and, as a result, she stayed outside on the rock platform. When they did not return, and sand and a boulder covered the entrance to the hole, she tried to scrape it all away with her hands, unsuccessfully. She then went to sleep and was seen the next day by Michael, and recovered the day after by Albert. However, in the typical timescape of the faërie realm, this took place in Michael's reality six and seven days later, but seemingly overnight in Irma's as she was largely unaffected, apart from a few cuts and bruises on her hands and, somewhat mysteriously, on her head. There are in both chapter 18 and the published text a number of references to head wounds suffered by Michael and Irma, but no description provided by Lindsay as to their origin.

In the present author's opinion an amalgamation of the two chapters, or editing of chapter 3 along with inclusion of chapter 18, or even publication of the original, unedited draft manuscript, would serve to better assist the reader in understanding what happened on the mountain that afternoon of St. Valentine's Day, 1900. Such an amalgamation has been created by the present author and can be accessed here. Through a reading of this, we can more clearly appreciate the events surrounding the disappearances. A brief summary of what we find follows.

Summary: Around 2pm, Miranda and three other schoolgirls - Marion, Irma and Edith - decide to explore Hanging Rock, despite being initially told by Mrs Appleyard not to do so. They are granted permission by French governess and teacher Mademoiselle Dianne de Poitiers. On the way, Edith, the youngest of the group, sees a strange "nasty" red cloud in the distance and gets hungry and scared. She observes Miranda, in a dream-like state, walk off ahead as if floating, followed by the two other girls. At this point Edith either leaves (chapter 18) or follows (chapter 3). In the chapter 18 alternative Edith leaves the group before they reach a strange monolith. As she escapes, she passes the elderly teacher Miss McCraw - most likely her changeling version - heading in the opposite direction, though dressed only in her underwear. In the chapter 3 version the three girls - Miranda, Marion and Irma - travel further on alone. They reach the top of the mountain and observe future events .... Peering down between the ringing boulders, they could just make out tiny figures coming and going, through drifts of rosy smoke.... Irma was aware, for a little while, of a rather curious sound coming up from the plain, like the beating of far-off drums. Irma was the only one to hear this sound. They then reach the strange monolith, where Miranda and Marion are subject to a strange, disorienting force. They move on and are then overcome by an energy which eventually causes drowsiness. They fall asleep. When Miranda awakes, a strange woman appears - the changeling version of Miss McCraw. She is violently thrown towards Miranda from the surrounding bush and rock. The three girls do not recognise this woman, who presents as a gaunt, raddled face trimmed with bushy black eyebrows - a clown-like figure dressed in a torn calico camisole and long calico drawers frilled below the knees of two stick-like legs. She asks the girls for their names, as she had apparently lost hers. [NB: This is a common event in faërie encounters, wherein the creature seeks the name of the person and thereby obtains some power over them, including the ability to entice]. The group of four now sees a strange hole magically appear in the space before them. The stranger's face then turns beautiful and radiant, after which her bony body partially transforms into a crab-like creature to facilitate entering a cave through a hole in the ground. Two of the girls - Miranda and Marion - follow her in. Irma stays behind, wary of the events occurring. She watches and waits, as eventually a landslide of sand and boulder covers the entrance. She is subsequently found on the mountain top, a week after disappearing. Here the story ends, with no mention of the ultimate fate of the now missing three individuals - Miranda, Marion and Miss McCraw.

Chapter 18 clearly sets Picnic at Hanging Rock within the traditionally British faërie realm of fantasy and mythological folklore. Many examples therein, spoken, written and recorded over the millennia, replicate events contained within Picnic at Hanging Rock. The final 1967 edition does not do this to any obvious degree. This faërie context is a logical assumption when we take into account the fact that Lindsay was raised in the English schooling tradition at a period in Australian history where colonial ties were strong and association with paranormal events would have substantially been perceived within the British cultural perspective of faërie. This relationship to the faërie realm is seen in the novel (1967 and 1987) and throughout the 1975 film and 2018 television series, in the following aspects and incidents:

- the stopping of watches as the party arrives at Hanging Rock (novel);

- mysterious shadows cast about the Hanging Rock environment (novel);

- the presence of invisible figures and mysterious voices and sounds encountered by the girls as they ascend Hanging Rock;

- the individuality of perception by the group that travels to the top of Hanging Rock (novel);

- the appearance to Miranda of the temporary changelings, i.e., mirror images of the four girls as they climb through the bush and past the rocks (2018 TV adaptation);

- the mysterious "nasty" red cloud seen by Edith (novel);

- the encounter with a powerful, energy emitting monolith which induces sleep, or a state of unconsciousness, upon the schoolgirls (chapter 18);

- Irma's observations from atop the rock of events past, present and future taking place below her (novel and chapter 18);

- the appearance of a distinct hole in the space before the schoolgirls and teacher, a precursor to a convex, spherical black hole (chapter 18);

- the creation of a Miss McCraw changeling (novel and chapter 18);

- the transformation of the "stranger" into a partially crab-like creature (chapter 18);

- the dilation of time throughout the disappearance episode and subsequent discovery of Irma a week later (novel and chapter 18);

- the schoolgirls and Miss McCraw leaving no tracks once they pass the lower reaches of Hanging Rock and start climbing (novel and chapter 18);

- Edith noting how the three schoolgirls appeared to slide across the ground, and Irma's feel were clean and unmarked when she was found (novel);

- Mademoiselle de Poitiers watching Miranda ... a little ahead glide through tall grasses, and Michael Fitzhubert watching her, as she crosses a creek, skimming over the water like one of the white swans on his uncle's lake (novel).

- the distortion of space, whereby the three schoolgirls and Miss McCraw disappear permanently and are never found (novel and chapter 18);

- Michael's encounter with the faërie realm during his search for the girls, resulting in locating Irma, then collapsing as he escapes (novel)

- the appearance of an unchanging light which generates no shadows, though it is twilight outside (novel and chapter 18).

Light features in the chapter 18 events, and this is significant. The faërie realm is traditionally said to exist in eternal twilight. As twilight descends upon Hanging Rock, the stranger entices the girls into the hole in the ground with the promise of a continuation of the artificial light of the faërie realm they are then within, and ultimately a brighter light. Miranda and Marion are excited by this.

As outlined in the above History of Fairies video, there are two types of faërie - light and dark - and it is the dark who are malevolent and kidnap children and young adults for breeding or other purposes. The dark stranger is using the promise of light as an element of its enticement. It would seem that Lindsay is reflecting this aspect of faërie mythology within chapter 18 in order to help explain the disappearance - a disappearance she was aware of in some form of reality.

All of these events speak of an encounter with the faërie realm. They in turn offer an explanation for the permanent disappearance of three individuals, temporary disappearance of one, and the partial transformation into a mythical creature of Miss McCraw's changeling. This explanation can be accepted regardless of whether one accepts the reality of the faërie realm, or its presence as a mere fantasy fiction device made use of here by Joan Lindsay.

Some commentators have suggested that Miranda and Marion subsequently transformed into faërie creatures - a swan and a snake - but the present author is not aware of any evidence for this, apart from the inclusion of the white swan motif throughout the text, as a spirit animal attached to Michael and representation of his idealised attraction to, and love / lust for, Miranda.

Joan Lindsay undoubtedly had direct knowledge, or experience, of the faërie realm, either through her readings since a child, in association with inherent psychic abilities, or simple circumstances, such as eerie encounters at Hanging Rock over the years. Her writings in this area are few and far between, though two examples have been noted from the 1920s and 1930s: