The art of Mickey of Ulladulla 1825-1891

Shoalhaven & South Coast: Aborigines / Indigenous / First Nations archive | Amootoo | Arawarra | Aunty Julie Freeman art | Berry's Frankenstein & Arawarra | Blanket lists | Broger | Broughton | Bundle | Byamunga's (Devil's) Hands | Cornelius O'Brien & Kangaroo Valley | Cullunghutti - Sacred Mountain | Death ... Arawarra, Berry & Shelley | God | Gooloo Creek, Conjola | Indigenous words | Kangaroo Valley | Jerribaley Cemetery | Mary Reiby & Berry | Mickey of Ulladulla | Minamurra River massacre 1818 | Moruya monster | Mount Gigenbullen | Neddy Noora breastplate | Timelong | Towwaa 1810 | Ulladulla Mission | Yams |

|

Drawn by “Mickie” an old crippled blackfellow of Nelligen, Clyde River, NSW 1875

......primitive art, uninfluenced by the white man.... (1893)

Contents

- Introduction

- Rediscovery

- Contemporary accounts

- Artworks

- Timeline

- Commentary

- References

- Acknowledgements

------------------------

1. Introduction

Mickey of Ulladulla (1820/1825 - 13 October 1891), also known as Mickey the Cripple or Mickey Flynn, is an Australian Aboriginal artist famous for his drawings of Indigenous culture and interactions with local settler society in the south coast region of New South Wales. He used two sticks to assist with walking, and in one of his drawings is portrayed wearing European clothes, a hat, and smoking a pipe (illustrated at right). A small collection of pencil, ink, crayon, watercolour and gouache drawings survive, numbering approximately a dozen works. All display Indigenous and non-Indigenous figures, flora and fauna, whilst there is also a single watercolour portrait of a coastal trading vessel. The works appear to date from the 1870s and 1880s and represent one of the few collections of art on paper done in a partially Western style by an Australian Aboriginal person during the nineteenth century. The present article brings together biographical information on the artist, lists surviving works, and discusses their content and significance. The definitive to date catalogue of his works is to be found in Andrew Sayers' Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century, with some 27 items listed (Sayers 1994), though another has been revealed subsequently. Sayers' chapter 3 - Drawing contemporary life - also discusses Mickey's life and art in some detail.

The motivation for the creation of the present article was a viewing of an exhibition of some 12 works at the Bundanon Art Museum in November 2024, alongside ongoing interest in Mickey's life and art from residents of the Shoalhaven and Ulladulla area interested in Indigenous cultural heritage. With precious little available online, this article aims to provide a readily accessible introduction to the art of Mickey of Ulladulla, along with links to original sources, enabling future research.

-----------------------

2. Rediscovery

Modern 'rediscovery' of the work of Mickey of Ulladulla can be said to have taken place on two occasions - the first in 1951, and then more substantially during 1994. Though exhibited in the Chicago Columbian Exhibition of 1893, notices of his works in published catalogues around the time were brief, single line entries only. Also, a collection of six Mickey drawings was included in a sketchbook of miscellaneous material deposited in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, prior to June 1918. It had been compiled by H.E. Gatliff and also included drawings by Tommy McRae. There does not appear to have been any reporting of this acquisition or public discussion of the works contained therein. This was to change, however, following the distractions of two world wars and a renewed interest in the history of Australia, including its Indigenous cultural heritage.

On 4 February 1951 a full page, illustrated article by Brian Crozier appeared in the Sydney Sun Herald newspaper, entitled What came before Namatjira? Primitive Art in Grafton Discovery. Two of Mickey's works, therein cited as by 'an unknown Aboriginal' were described and discussed in detail in print for perhaps the first time.

|

| Sun Herald, Sydney, 4 February 1951. |

At the time nothing much was known of Mickey and the article mainly dealt with the works from an ethnological or anthropological and artistic perspective. The text reads as follows:

What Came Before Namatjira?

Primitive Art in Grafton Discovery

By Brian Crozier

Take a close look at the two pencil and wash drawings on this page. They are the work

of an unknown aboriginal. They are perhaps unique - the intermediate stage between the bark paintings of the primitive aborigines and the westernised paintings of a Namatjira. They were painted 13 years before Federation in 1888, and have been in the care of Grafton municipality since 1941. How is it that they have only now come to light? It is really a simple case of chance. The story that began 53 years ago might have had no further sequel if Sali Herman, the artist, had not been lecturing in Grafton a few weeks ago. In the council chambers one day, when talking to the Mayor, he happened to notice the two pictures on a wall. Interested, he asked their history. Largely, the history of the paintings is lost in the dimness of old memories. All that is known of the artist is that he was called "Ulladulla Micky" and lived in Ulladulla, on the South Coast of New South Wales.

The late Mr. Wilford Johnson, a former station manager of the lower Clarence District, whose widow, now 93, is now living in Grafton, obtained the paintings nearly 60 years ago. Mrs. Johnson presented them to the Clarence River Historical Society in 1937. The Grafton City Council is trustee for the society. Back in Sydney, Mr. Herman called on me and told me about the paintings. His enthusiasm was infectious, so I wrote to the Mayor of Grafton and asked him if the municipality would send me the paintings, on loan. Very kindly, the municipality did. And so, although the history of the Ulladulla paintings has been rounded off with the death of the painter, their real story is only now beginning. For they open up, from the artistic point of view, the whole question of the value of primitive art; while to the anthropologist, they must be of exceptional interest. Clearly, both sides had to be discussed. So last week Sali Herman and I called on Professor Elkin, the anthropologist, to ask him for his views.

On our way to the university, Mr, Herman (an "old New Australian," who, with 14 years' residence and four years' in the Australian Army, has every right to consider himself a dinkum Aussie) gave me his own views on the Ulladulla paintings. No discussion on aboriginal art can go far without a mention of Namatjira, and this was no exception.

"Namatjira proves to me, with his watercolours," said Mr. Herman, "that the aboriginal, like most primitive people, can be assimilated into our way of life. Rex Battarbee taught him the use of watercolour, plus the way we paint a certain subject (in this case landscape). "But in my opinion, Namatjira's watercolours prove only the artist's dexterity. What he says is not his own language. In his work, he is a perfect converted European, but does this correspond to his way of life? On the other hand, in the two Ulladulla watercolours, while we can see some of the white man's influence, the artist does not imitate our technique, still less the subject matter. He still talks his own language, and for that reason has much more character and charm. In saying this, I do not wish to detract from any credit that Namatjira deserves. But whereas I consider his work an excellent imitation, I regard the Ulladulla artist paintings as a sincere expression in a natural language. While they are more primitive, I think they are of greater artistic interest."

This was where I felt some disagreement with Mr. Herman, and I told him so. To me, the fascinating Ulladulla paintings are of greater anthropological than artistic value, though the artistic value certainly exists, and is of a high order. I shall return to these arguments later. Meanwhile, there are Professor Elkin's views to consider. Professor Elkin, just back from a five-week visit to Ceylon and India, welcomed us in his study at the university. On the walls were a Namatjira watercolour and several watercolours by other aborigines of the Alice Springs area. I showed him the paintings, and he went over them in detail, giving us the explanations we reprint below the pictures on this page.

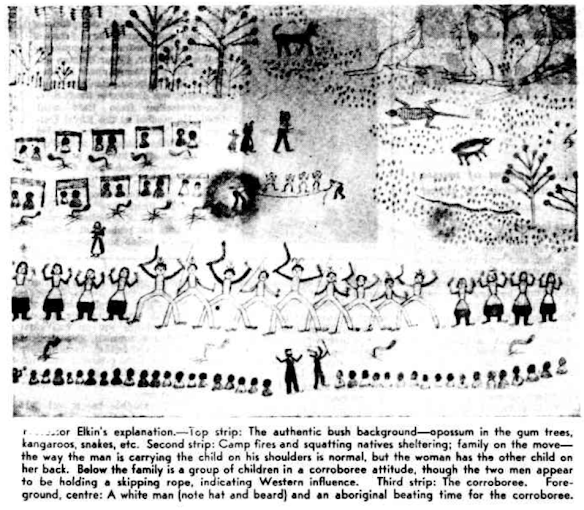

Professor Elkin's explanation. - Top strip: The authentic bush background - opossum in the gum trees, kangaroos, snakes, etc. Second strip: Camp fires and squatting natives sheltering; family on the move, the way the man is carrying the child on his shoulders is normal, but the woman has the other child on her back. Below the family is a group of children in a corroboree attitude, though the two men appear to be holding a skipping rope, indicating Western influence. Third strip: The corroboree. Foreground,, centre: A white man (note hat and beard) and an aboriginal beating time for the corroboree.

Detail of the second Ulladulla painting. Above: Birds in flight. Below: A fishing scene. Note the great detail in which every fish and bird is drawn. Professor Elkin's comment: "Birds and fish mean food to the aborigines. They are well aware of the different species, which are edible, and which parts are edible. Hence the importance they attach to drawing them in great detail."

Inevitably, the discussion came round to Namatjira again.

"It is my view," said Mr. Herman, "that these two pictures are far superior to this (pointing to the Namatjira on the wall). My criticism of Namatjira is that he doesn't build on the culture of his own people."

"The answer to that," said Professor Elkin, "is that Namatjira, a Central Australian aboriginal, really had nothing to build on. In Central Australia, the rock is mostly very poor to paint on, and the results are uninspiring from anyone's point of view. The art of that area consists mostly of concentric circles and parallel lines at various angles. These patterns have symbolic meanings which differ from clan to clan, even in areas only 50 miles apart. There is no attempt at any kind of representational art. "On the other hand, these two pictures from Grafton were apparently painted by a native of the Yuin tribe, in the Ulladulla region. And there, as in Arnhem Land, he would have had a rich store of artistic tradition to draw upon - bark paintings, rock carvings, and so on. "It was quite different with Namatjira, as I have often pointed out. Having nothing to build on in his own tribal traditions, he took immediately to the idea of the white man's idea of watercolour as something worth doing." I asked Mr. Herman if these facts affected his earlier opinion. He looked thoughtful for a moment, then said: "No, on the whole, I think my opinion still stands. Namatjira's art remains an imitation of the West. But I must admit that he had an excuse for imitating Western art of which I was not aware.

Now that you have heard the arguments for and against ,what do you think? It all depends on what value you attach to primitive art, bearing in mind that at a certain stage in its development primitive art is no longer truly primitive. Let me explain. Genuine primitive art is the work of (a) the truly primitive savage, who has had no contact with more developed forms of civilisation, and (b) small children, preferably between the ages of 3 and 7.

There are certain very attractive qualities in genuine primitive art: Freshness of approach, uninhibited charm, a natural feeling for decoration. These are all present in considerable degree in the Ulladulla paintings, with their engaging lack of perspective, their spontaneous sense of rhythm, and their remarkable decorative feeling. But are they necessarily of greater artistic value, because they are so many stages nearer the genuine primitive, than the art of Namatjira and of the other Central Aborigines who have followed in his footsteps? Must Namatjira's Westernised dexterity detract from the merit of his paintings?

But Mr. Herman's views raise an interesting point: The cult of the primitive in modern art. Why do savages and civilised children draw and paint the way they do? Partly, I fancy, through a special, way of seeing things, and partly through lack of knowledge and lack of skill.

Now take the case of a mature man or a woman who has never painted before, but is suddenly invited to use a brush and pigments. The maturity of vision in many cases is there, but neither the knowledge nor the skill. The result is often pleasing in precisely the same way that primitive art is pleasing. But must we therefore rank this result which, however pleasing, is often quite accidental, higher than imaginative painting produced with all the skill of a professional artist aiming at certain results and achieving them through knowledge? Yet that is often what we are invited to do. It all goes back to those twin pillars of the modern School of Paris, Picasso and Matisse.

Now Picasso is not in any sense a primitive. This Spaniard who settled in France so long ago that he has become identified with French art, who has startled the world fairly regularly during the first half of this century, and in the process has amassed a fabulous fortune; this Spaniard knows what he is about. But he became enamoured of Negro sculpture (the art of the Congo) before the first World War, and it has had a profound influence not only on his own painting, but also on the painting of his many imitators. Matisse is a very different case. He, too, knows what he is about. His early paintings were landscapes that would outrage no suburban home and that no one nowadays would mistake for the work of Matisse. But he set out, deliberately, to paint as children and savages do, and he has done so ever since.

Does all this point a moral for the modern artist? Perhaps it does, and perhaps the moral is this: Unless you are a Picasso or a Matisse, do not imitate the primitives; if you happen to have a primitive way of seeing things, make sure you have the technical means of expressing yourself on canvas. The Ulladulla paintings, which are genuine primitive art only slightly modified by Western influence, are of real value. That cannot always be said of our modern primitives; Picasso and Matisse are exceptions, and both are bad models for the young.

The most significant events in the rediscovery of the work of Mickey of Ulladulla, and of similar Australian Indigenous artists, occurred during 1994 with the publication of the book by Andrew Sayers, Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century, and the associated exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia. A number of biographical articles have been published since which bring together those few snippets of information available on the artist. Some of these are reproduced below to provide a snapshot of his public life, for Mickey's relationship with the local Indigenous community is only known through those aspects revealed in his work, especially those drawings of corroboree ceremony and fishing activities. He is referred to as '....a famous chief of the Ulladulla tribe' in a book published after his death, which points to a local heritage (Bancroft 1893). In the catalogue essay for the 1994 exhibition, there is only the following brief mention of Mickey:

Much less is known about the life of Mickey of Ulladulla (or Mickey the Cripple, as he was sometimes known). In the 1880s he made drawings which combined the native flora and fauna of the south coast of New South Wales with depictions of small boats, ships and sawmills. Mickey's is a contemporary world — the microcosm of Aboriginal life on the south coast in the last decades of the century. Towards the end of his life he lived on the eight-and-a-half hectare reserve at Ulladulla where the local people made a living from fishing and providing labour to the port. When Mickey died in 1891 the local paper noted his passing and mentioned his 'very fine pencil sketches'. (Sayers & Cooper 1994)

A more fulsome biographical outline was provided by Sayers for the Australian Dictionary of Biography, published in 2005:

Mickey of Ulladulla (c.1820–1891), Aboriginal artist, was born on the south coast of New South Wales, a member of the Dhurga people. The first written record of him was a note on some of his drawings in the collection of the Mitchell Library, Sydney: Drawn by 'Mickie' / An old crippled blackfellow / of Nelligen, Clyde River NSW / 1875. Later drawings, dating from the 1880s, were annotated with inscriptions describing the artist's location as Ulladulla. By the 1840s, Aboriginal men at Ulladulla were employed by settlers in reaping, tree felling and trading in native fauna. Women were employed in such pursuits as digging potatoes and husking maize. As the south coast industries developed, Aboriginal labour was used on farms, in sawmills and on wharves. The principal activity, however, was fishing. Mickey's drawings recorded some of these activities. In one, a man supporting himself on two sticks (almost certainly a depiction of the artist) was shown selling brooms. Most of his drawings were made in the 1880s at Ulladulla. Many appear to have been pairs: one part depicting the corroboree, the other depicting fishing activities. He developed a pattern for these sketches. Those of corroborees included a row of spectators along the lower edge of the composition, while centrally placed, in European dress, was the man with crutches, the artist himself. In his fishing scenes, specific vessels were depicted, such as the boats given to the Ulladulla community by the Aborigines Protection Board and the Peterborough, a steamer that made a weekly trip between Ulladulla and Sydney in the 1880s and 1890s. Mickey's medium was a mixture of pencil, water-colour and coloured crayons. Like his fellow Aboriginal artists of the nineteenth century Tommy McRae and William Barak, he had a particular relationship with members of the European community, who provided materials and who ensured the preservation of the works. Mickey's patron was Mary Ann Gambell, the wife of the Ulladulla lighthouse keeper, who lived close to the Aboriginal Reserve at Ulladulla and had a reputation as a friend of Indigenous people. Mickey of Ulladulla died on 13 October 1891. He may have succumbed to the virulent strain of influenza that caused a minor epidemic in the town in October and November that year. A brief report of his death in the local newspaper described him as 'gifted with some of the qualities of an artist. He produced some very fine pencil sketches, and indeed showed ability in that direction'. In 1893 the Board for the Protection of Aborigines and two local officials (George Ilett of Milton and John Rainsford) showed five of Mickey's drawings at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, United States of America. Ilett was awarded a bronze medal for exhibiting work that was described as 'unique and valuable as a specimen of primitive art, being uninfluenced by the white man'. Mickey of Ulladulla's drawings are in many public collections including the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, the National Library of Australia and the National Gallery of Australia, all in Canberra, and the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

The majority of subsequent biographical outlines draw from the research of Sayers. Historian Keith Vincent Smith compiled a second biography for Design and Art Australia Online (2011):

Mickey of Ulladulla was an Aboriginal artist active in the nineteenth century on the south coast of NSW. Five of his paintings were included posthumously in the catalogue of exhibits in the NSW Courts at the Chicago Exposition in 1893. Micky or Mickey of Ulladulla (1825-1891), also called Mickey Flynn, was an Aboriginal artist who used pencil and watercolour paints to create lively scenes crowded with Aboriginal people and their daily life, animals, plants, fish, boats and ships, in a naïve European style. Mickey found fame after his death when five of his works were exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in the United States of America in 1893. When he died on 13 October 1891, Mickey had been living for many years on the Aboriginal Reservation at Ulladulla and was said to be nearly 70 years of age. One year after his death a visitor described the lifestyle of Mickey’s Dhurga people there in the Sydney Morning Herald (12 April 1892): “Some 40 or 50 blacks live here after the fashion of Europeans, having their houses and cooking utensils, and gardens. They live mostly by fishing.”

Mickey was born on the south coast of New South Wales, perhaps at Nelligen, a village nine kilometres along the Clyde River from Batemans Bay, some 50 kilometres south of Ulladulla. Three pencil drawings in the State Library of New South Wales in Sydney are noted as ‘Drawn by “Mickie” an old crippled blackfellow of Nelligen, Clyde River, NSW 1875’. One of these, 'Ceremony’, a corroboree scene, is attributed to ‘Old Micke”. These images were donated on 22 January 1935 by ‘Miss M. Olley’. It was tempting to think this could be the artist Margaret Olley (1923-2011), but she was only 12 years old at the time. The donor was most likely Miss Matilda Sophia Olley, daughter of the Reverend Jacob Olley, a Congregational minister for many years at Ulladulla, where she was born in 1873. What little is known about Mickey’s life is well covered by Andrew Sayers in Aboriginal Artist of the nineteenth century, published in 1994 by Oxford University Press in association the National Gallery of Australia. His art speaks for itself.

Five paintings by ‘“Mickey”, an Aboriginal of the Ulladulla Tribe, N.S.W.’ were included in the Catalogue of exhibits in the New South Wales Courts (Sydney 1893) at the Chicago Exposition. In his Book of the Fair (Chicago 1893), American author Herbert Howe Bancroft said they were ‘executed by a famous chief of the Ulladulla tribe, dealing principally with hunting and fishing scenes’. George Ilett of Milton, NSW, was awarded a bronze medal for exhibiting two of Mickey’s works described as ‘unique and valuable as a specimen of primitive art, being uninfluenced by the white man’. Mickey of Ulladulla is represented in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia, the National Library of Australia and the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), all in Canberra, the State Library of New South Wales in Sydney and the Clarence River Historical Society at Grafton, New South Wales. A few more are in private hands. As Sayers points out, Mickey drew with pencil and watercolours on large sheets of paper, often in pairs, one usually depicting a corroboree and the other a fishing or boating scene. He was encouraged to paint by Mary Ann Gambell, wife of the lighthouse keeper at Ulladulla.

Mickey was lame and walked with the aid of two sticks. He puts himself into some of his pictures, always wearing a long coat and a hat. In one, ‘Old Mickey’ is written below his figure. A painting of the coastal steam ship Peterborough is captioned: ‘Drawn by “Mickey”, an Australian Aboriginal. A cripple over 60 years of age. 1888’. In another work, Mickey is glimpsed near a rack of brooms, holding out a broom he has for sale. A note written on the reverse of his painting ‘Ceremony’ reads: ‘Drawn by Old Micke the conductor of the corobbary before the Duke of Edinburgh’. More than 300 Aboriginal men, women and children, many from the south coast of New South Wales, assembled to stage a welcome corroborree at Clontarf in Sydney’s Middle Harbour for Queen Victoria’s second son, aged 23, who was touring the Australian colonies in the royal sloop Galatea. The men were provided with pipes, shirts and trousers and the women with blankets, in order, according to The Empire (11 March 1868) ‘to do honour to “the Queen’s picanniny” as they call the Prince, in befitting costume”. Mickey’s corroboree, planned for 12 March 1868 never took place because Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, was shot and wounded by an Irish rebel named Henry James O’Farrell, who was later hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol. The figures of dancing men in Mickey’s picture, waving spears and boomerangs, wear trousers. The dancing women wear skirts, but the seated women are wrapped in blankets.

Like chapters in a visual autobiography, Mickey’s paintings illustrate the unique Aboriginal viewpoint. His subjects are the Indigenous people, plants and animals of Ulladulla’s saltwater environment. He celebrates their spiritual life: ritual revenge combats with spear and shield, and corroborees, in which painted stick figures act out stories and myths in song, music and dance. He pays attention to details of the rigging of ships’ sails and the species of snapper and other fish and sharks that he catches with his pencil and watercolours. A constantly repeated motif in his corroboree drawings shows Mickey, supporting himself with his sticks, standing with the spectators at the ceremony, next to a song man beating out the rhythm with his clap sticks. Through the legacy of his art Mickey of Ulladulla is still telling us stories.

It is interesting to note that, during a visit to Adelaide in November 1867, Prince Alfred - big one Queen's little picanniny - was presented with a corroboree and kangaroo hunting, similar to what had been planned for in Sydney. In At home: Mickey of Ulladulla (2015) comments are made in regards to Mickey's artworks and background:

Mickey of Ulladulla, along with William Barak, Oscar from Cooktown and Tommy McRae, are artists who were wedged between their traditional Aboriginal lifestyle and one radically changed by colonial expansion in full swing during the late 1800s. These men and their art, describes a time after their tribal lands had been broken up and given to sheep; when their families and extended families had been clustered together on the remnants of what remained; when Christian missions and the Aborigines Protection Board had begun to actively intervene in the lives of Indigenous people; and when many Aboriginal people lived in resultant poverty and destitution. Not much is known about Mickey of Ulladulla’s early life, though the words ‘Drawn by “Mickie” an old crippled blackfellow of Nelligen, Clyde River, NSW 1875‘ inscribed some of his pencil drawings in the State Library of NSW provide a few clues. We know that from the 1840s Aboriginal men from Ulladulla were employed by settlers to fell and mill cedar, as well as in fencing, fishing and farming. We know Mickey had a patron, Mary Ann Gambell, the wife of the Ulladulla lighthouse keeper, who lived close to the Aboriginal Reserve at Ulladulla who was kindly to Indigenous people. And we know his language group was Dhurga. We also know that five paintings by “Mickey” were exhibited at the Chicago Exposition in 1893 by the Board for the Protection of Aborigines and two local officials. Ironically, one of those officials George Ilett of Milton, was awarded a bronze medal for exhibiting two of Mickey’s works as valuable specimens of ‘primitive art, uninfluenced by the white man’. Such were the times. Mickey’s work provides important documentation, social commentary and insight into the way Indigenous culture survived ... despite exile and banishment. But a whole lot more can be gleaned from the work itself. Using pencil, watercolour and crayons Mickey sketches various ceremonies, equipping and decorating his dancers carefully. Body paint, feathers and weapons are picked out with colour, leading the eye through the story. He rigs his fishing vessels accurately, and cheerfully depicts the Peterborough steamer – a supply ship for the settlement – down to its very blue hull and matching stream of smoke. What’s unique about Mickey’s work is that it provides important documentation, social commentary and insight into the way Indigenous culture survived and was, and still is, transmitted despite exile and banishment. He draws his people; he describes and details corroborees and ceremonies. And he depicts himself – an old man dressed in European clothing, caught in a rapidly changing world – propped on tall crutches, always present, watching, seeing and remembering. (Museums & Galleries of NSW 2015)

-------------------

3. Contemporary accounts

In searching for contemporary sources referring to Mickey, there is precious little. Reasons for this include the fact that Aboriginal people were very much forced into a situation of being fringe dwellers during the first century and a half of the European settlement of Australia, especially in settled coastal areas of south-eastern Australia. They were little seen, and little spoken about or referred to by so-called 'polite society.' Needless to say, this discrimination gave rise to a neglect of the compilation of official records such as birth, death and marriage information, or to recordings of aspects of Indigenous culture and heritage. As the Aborigines were considered to be heading towards extinction as a race by the end of the nineteenth century, it was often only with the death of one of those few prominent Elders remaining that reference was made in local newspapers. The life of Mickey of Ulladulla would therefore have passed largely without notice were it not for his age, artwork and open engagement with people.

The earliest dated record is the inscription on one of his artworks, namely:

Drawn by “Mickie” an old crippled blackfellow of Nelligen, Clyde River, NSW 1875

On 13 December 1881 a story appeared in the Glenn Innes and General Advertiser comparing Mickey's work with Raphael and Michelangelo:

Our blacks are smartening up, and there is every appearance now that some of them will 'ere long be quite capable of filling the leading positions in the land, such as pound-keeperships, Lord Bishoprics, and Town-Hall contractors. At the late Milton Shriw, one dusky Raphael, named "Mickey" took the special prize for pencil-drawing. The old aboriginal theory that when a blackfellow dies he "jumps up white fellow" therefore goes to grass, because it is very evident now that Milton Mickey is simply a resurrected charcoal copy of the Roman Mickey Angelo.

A copy of this article - referred to as a 'satirical squib' - appeared in the Shoalhaven Telegraph of 5 January 1882, with some additional comments. A brief obituary notice appeared in the Milton and Ulladulla Times of 17 October 1891 as follows:

An Old Identity.

Most of our readers are aware of the old aboriginal "Micky"' who for a long time has been living at Ulladulla. On Tuesday night the old fellow went the way of all flesh. The old fellow must have been close on 70 years of age at the time of his death. Unlike most of his race Micky was gifted with some of the qualities of an artist. He produced some very fair pencil sketches, and indeed showed ability in that direction.

Nothing could be found referring to him prior to this. On 5 September 1903 a brief item appeared in The World's News, Sydney, referring to one of Mickey's artworks.

A Remarkable Pencil Drawing.

Many people in the State of New South Wales are not aware of the fact that the Australian aboriginal has the faculty for drawing. Yet such is proved to be the case by Mr. John Rainsford, C.P.S., Temora, New South Wales, having in his possession a drawing by a South Coast black known as "Mickey Flynn," and who died at Ulladulla on October 13, 1891, aged 65. The drawing represents a corroboree of natives armed with boomerang and spear. Seated round are the women and children as spectators. In the distance the dwellings of the tribe are to be seen. Kangaroos making love to each other are also described. A snake is depicted in the grass. Fishing at Ulladulla is illustrated, and when particular attention is paid to the picture the natural movement of each kind of fish is most accurately described. The picture was exhibited at the Chicago Exhibition some few years ago, and commanded a good deal of attention. Mr. Rainsford intends sending the picture to one of the leading auctioneers in London for sale should a satisfactory price not be obtained in the State.

The Colonial Art in the Illawarra website states the following, though no precise reference is provided:

Mickey had a patron, Mary Ann Gambell, the wife of the Ulladulla lighthouse keeper, who lived close to the Aboriginal Reserve at Ulladulla, who was kindly to Indigenous people. It's also understood that the local postmistress provided Mickey with art materials.

Mrs Gambell (d.1897) was the wife of William Gambell (1828-1912), and a long time supporter of the local Aboriginal people. The minister at her funeral noted the following of her compassion:

Especially was this the case with those poor neglected children of the wilds, the dark skinned residents at " the camp." Her kindness to them was unbounded ; her door was always open to them, her ear never weary of listening to their complaints, and she ever keenly resented an adverse comment on these, the less favored specimens of our race. That they mourned her loss deeply was evident from the long line of dusky mourners.

-----------------------

4. Artworks

All works are on paper and illustrated below the description, where available. Known artworks are included in the following collecting institutional collections, totalling 27 items and catalogued according to Sayers (1994):

- National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (2 items).

- National Library of Australia, Canberra (2 item).

- Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra (8 items).

- Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney (9 items).

- Schaeffer House Museum, Grafton (3 items).

- Ilett Collection, Glenbrook (2 items)

* National Gallery of Australia

#1 / U1 - [Corroboree], pencil, ink, coloured pencil, 43.8 x 68.5 cm, National Gallery of Australia. Purchased 1991. >Illustrated Sayers 1994. Provenance: created by Mickey of Ulladulla, New South Wales, Australia, c.1888; acquired by the Walter family, Moruya, New South Wales, Australia, 1888 or later; by descent to Ilma Walter, Moruya, 1971 or before, who bequeathed it to the Church of England Moruya, 1971, which offered it at auction, (lot 537) Angus and McNicol, Moruya, 24 March 1973, where it was bought by George Henry Freedman, Sydney, 1973, who sold it to the National Gallery of Australia, 1991.

#2 / U2 - [Fishing, flora and fauna], pencil, watercolour, gouache, 43 x 68cm, National Gallery of Australia. Provenance: created by Mickey of Ulladulla, New South Wales, Australia, c.1888; acquired by the Walter family, Moruya, New South Wales, Australia, 1888 or later; by descent to Ilma Walter, Moruya, 1971 or before, who bequeathed it to the Church of England Moruya, 1971, which offered it at auction, (lot 537) Angus and McNicol, Moruya, 24 March 1973, where it was bought by George Henry Freedman, Sydney, 1973, who sold it to the National Gallery of Australia, 1991. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#3 / U3 - [Corroboree, native flora and fauna], pencil and watercolour, 39.5 x 55.4 cm, National Library of Australia. Inscribed: F.H. By the late Mickey the Cripple Aborigine Ulladulla.

#4 / U4 - [Fishing, native flora and fauna], drawing, pencil and wash, 44 x 55.4 cm, National Library of Australia. Inscribed: F.H. By the late Mickey the Cripple Aborigine Ulladulla.

* Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

#5 / U5 - [Ceremony, native flora and fauna, empty camp], pencil, coloured pencil, watercolour, 27.6 x 32.6 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra. Provenance: Mary Ann Gambell; thence to W. Gambell, Balmain; acquired by the Institute through F. McCarthy.

#6 / U6 - [Fish, pelicans, Black Swans], pencil, watercolour, 28 x 38 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra.

#7 / U7 - [Fishing, native flora and fauna], pencil, coloured pencil, watercolour, 43 x 55 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra.

#8 / U8 - [River with boat, fish, kangaroo and sawmill], pencil, watercolour, 36.6 x 56 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#9 / U9 - [Ship with fish], pencil, coloured pencil, 27.7 x 45 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#10 / U10 - [Boats, fish, native flora and fauna], pencil, watercolour, 38 x 55.2 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#11 / U11 - [Ship], pencil, coloured pencil, watercolour, 36 x 56.3 cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra.

#12 / U12 - [Ceremony, games, native flora and fauna], pencil, watercolour on paper mounted on board, 37.6 x 56cm, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS), Canberra.

* State Library of New South Wales

#13 / U13a - The "Peterborough" steamer, at Ulladulla / drawn by "Mickey", an Australian Aboriginal. A cripple over 60 years of age. 1888, pencil and watercolour, 26.5 x 35.7 cm, State Library of New South Wales. Catalogue no. V/92. Provenance: Owned by the Illawarra Steam Navigation Co., the 'Peterborough' made weekly trips between Ulladulla and Sydney carrying market produce and passengers during the 1880s-1890s. Donated by M. Olley, 21 January 1935.

#14 / U13b - [Ceremony], pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 32 x 39.8 cm, State Library of New South Wales. Catalogue no. V/93. Inscribed 'Old Mickey' lower right. Provenance: Donated by M. Olley, 21 January 1935.

#15 / U14 - [Scenes of Aboriginal life], drawing, pencil, ink, crayon and watercolour on paper, ......'Scenes of Aboriginal life' (detail), ca. 1880s, pencil, coloured pencil and watercolour drawing, 55.1 x 74.2 cm, State Library of New South Wales. Catalogue no. XV/68.

#16 - [Ceremony], lower section only, drawing, pencil and coloured pencil on paper, 16.5 x 40.5 cm, State Library of New South Wales. Catalogue no. SV/49.

#17 / U15 - [Ceremony, native flora and fauna, horse], pencil, 33.7 x 41.5 cm, ML A364, State Library of New South Wales.

#18 / U16 - [Figure groups, including man being pulled from a horse], pencil, 23.7 x 13.8 cm, ML A364, State Library of New South Wales. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#19 / U17 - [Ceremony with spectators], pencil, 19 x 24cm, ML A364, State Library of New South Wales.

#20 / U18 - [Birds], pencil, 19 x 24 cm, ML A364, State Library of New South Wales.

#21 / U19 - [Fish], pencil, 14.1 x 24.3 cm, State Library of New South Wales. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#22 / U20 - [Three boats], pencil, 19.5 x 22.6 cm, ML A364, State Library of New South Wales. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

* Grafton Historical Society

#23 / U21 - [Ceremony], pencil, coloured pencil and watercolour, 39 x 51 cm, Schaefer House Museum, Grafton Historical Society. Reference: Crozier (1951).

Professor Elkin's explanation.- Top strip: The authentic bush background-opossum in the gum trees, kangaroos, snakes, etc. Second strip: Camp fires and squatting natives sheltering; family on the move the way the man is carrying the child on his shoulders is normal, but the woman has the other child on her back. Below the family is a group of children in a corroboree attitude, though the two men appear to be holding a skipping rope, indicating Western influence. Third strip: The corroboree. Foreground,, centre: A white man (note hat and beard) and an aboriginal beating time for the corroboree. Detail of the second Ulladulla painting. Above: Birds in flight. Below: A fishing scene. Note the great detail in which every fish and bird is drawn. Professor Elkin's comment: "Birds and fish mean food to the aborigines. They are well aware of the different species, which are edible, and which parts are edible. Hence the importance they attach to drawing them in great detail."

#24 / U22 - [Fishing scene], pencil, watercolour and gouache, 39 x 51 cm, Schaefer House Museum, Grafton Historical Society. Reference: Crozier (1951).

Detail of the second Ulladulla painting. Above: Birds in flight. Below: A fishing scene. Note the great detail in which every fish and bird is drawn. Professor Elkin's comment: "Birds and fish mean food to the aborigines. They are well aware of the different species, which are edible, and which parts are edible. Hence the importance they attach to drawing them in great detail."

#25 / U23 - [Ceremony, native flora and fauna], pencil and watercolour, 20.2 x 32.7 cm, Schaefer House Museum, Grafton Historical Society. Reference: Crozier (1951).

* Private (Ilett Family) Collection

#26 / U24 - [Ceremony, scenes of daily life, native flora and fauna], pencil and watercolour, 41 x 49 cm, Private Collection, Glenbrook. Inscribed: Drawn by Mickey / Native / Ulladulla. Provenance: George Ilett, Milton; his daughter Portia Ilett; by descent to present owner. Illustrated Sayers 1994.

#27 / U25 - [Fishing, scenes of daily life, native flora and fauna], pencil and watercolour, 41 x 49 cm, Private Collection, Glenbrook. Inscribed: Drawn by Mickey / Native / Ulladulla. Provenance: George Ilett, Milton; his daughter Portia Ilett; by descent to present owner (Sayers 1994).

-----------------------

5. Timeline

1820

- Mickey is born, though elsewhere the date is cited as 1825 or 1826. No information about ancestry, family and tribal association is known, apart from his later being referred to as chief of the Ulladulla tribe.

1867-8

- Mickey manages the staging of a corroboree at Clontarf on Sydney Harbour for the visiting Duke of Edinburgh.

1875

- one of Mickey's artworks is inscribed with the date 1875.

1881

- 19 November, Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser: Milton Show .....Pencil-drawing — corroboree, ships, animals, fish, &c. — by 'Mickey,' an aboriginal, special prize. Mickey wins a prize for his art at the Milton Show.

1888

- Numerous works by Markey are ascribed to this date.

1891

- 13 October: Mickey dies, aged 65, possibly from the influenza pandemic which occurred in Ulladulla that year.

1893

- Five paintings by Mickey of Ulladulla are displayed by the Board for the Protection of Aborigines at the World's Columbian Exhibition, Chicago. The display is compiled by George Ilett of Milton.

- 23 February, Illawarra Mercury: Messrs. J. Rainsford and G. Ilett o£ Milton have each forwarded an aboriginal picture valued at £10, to the Chicago Exhibition. Ilett is Bailiff to the Milton and Ulladulla District Court.

- 25 November, Milton and Ulladulla Times: Mr. George Ilett, of East Milton, has obtained an award for an exhibit in the Ethnological Section of the Chicago Exhibition. NB: This is for a display which included art by Mickey of Ulladulla, though no mention of him is made in this report.

1918

- June: A number of works by Mickey are included in a sketchbook deposited in the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, prior to this date.

1935

- Mrs. Matilda Olley donates works by Mickey to the State Library of New South Wales.

1937

- Mrs. Wilford Johnson donates two works to the Grafton Historical Society. They are described in Crozier (1951).

1951

- Brian Crozier article on the discovery of two works by Mickey in Grafton, previously donated to the local historical society.

1991

- The National Gallery of Australia purchases a work by Mickey of Ulladulla.

1994

- Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century [exhibition], National Gallery of Australia, 15 October 1994 to 18 July 1995. Shown in association with the release of Andrew Sayer's book of the same name.

1997

- Possessed : an exhibition of treasures, State Library of New South Wales;[exhibition], March 1997 - June 1997, Campbelltown Arts Centre. Includes works by Mickey.

2024

- 2 November: Bundanon exhibition opening. Includes an exhibition of 12 works by Mickey.

-----------------------

6. Commentary

From the above, it can be seen that there are a number of repeated motifs in Mickey's work. They include the following:

* A corroboree with performances being observed

* Dancing male figures

* Dancing female figures

* Seated array of largely females, rear of head view observing the ceremonial dance

* Individuals taking unique actions aside from the corroboree (refer below)

* Native animals - kangaroo, possum, koala, wombat, spiney anteater, cockatoo, goanna, snake, swan, pelican.

* Native fauna - trees, bushes and grasses

* Sea creatures - specific fish, sharks

* European figures, male and female

* Implements such as spears and throwing devices

* Non native animals such as horses and dogs

* Non native items such as brooms, ......

Some of the disparate actions being undertaken by figures in the drawings include:

* A man on his knees cowering and obviously distressed or in some sort of meditative stance

* A figure appearing to be flogged with a whip

* People fishing

The drawings of Mickey of Ulladulla contain a wealth of images relating to people, flora and fauna, sea-going vessels and everyday items. Whether it be a small reddish-orange fish in U10 which reminds one of Disney's Finding Nemo, or an Aboriginal man stocking a sacred fire for smoking away spirits, the artist has provide us with a veritable dictionary of everyday life. The works may be labelled, primitive or naïve, but one thing they are, and that is rarely stated, is - complex. One can therefore only dig deeper and deeper when face with such an open book.

-----------------------

7. References

Aboriginal (Dhurga) word list [curriculum resource], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, n.d. Illustrated at right.

At home: Mickey of Ulladulla, Museum and Galleries of New South Wales, 18 March 2015.

Bancroft, Herbert Howe, Book of the Fair, Bancroft Publishers, Chicago, 1893.

Bundanon announces 2024 Season 3 exhibition - Bariwariganyan: Echoes of Country [media release], Bundanon, accessed 18 October 2024.

Colonial Art in the Illawarra [website], n.d., accessed 2 November 2024.

Crozier, Brian, What came before Namatjira? Primitive Art in Grafton Discovery, Sun Herald, Sydney, 4 February 1951.

Dolan, David, Aboriginal artist of the nineteenth century [review], Canberra Times, 4 February 1995.

Drawings by Tommy McRae and Mickey of Ulladulla, circa 1860s - 1901 [manuscript], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney. Contents: 9 pen and ink drawings, 7 pencil drawings, 2 albumen photo, 1 fascicle with 11 pages of news cuttings & 10 pages of manuscript, 1 disbound library boards, and original covers of sketchbook. Original in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia.

Grishin, Sasha, Aboriginal art for white people, Canberra Times, 28 October 1994.

Killeen, Richard, Mickey of Ulladulla 1995 [artworks], Queensland Art Gallery and Gallery of Modern Art, 1995. Polymer paint on aluminium, 32 pieces.

Mickey of Ulladulla, in bagan bariwariganyan: echoes of country [exhibition], Bundanon Art Museum, 2 November 2024 – 9 February 2025.

Mickey of Ulladulla [8 catalogue entries], Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, Canberra, n.d.

Mickey of Ulladulla [collection of images], Pinterest, n.d.

Mickey of Ulladulla, Wikipedia, accessed 2 November 2024.

Price, Kaye, ed. Knowledge of Life: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia, Cambridge University Press,2015, p.81.

Sayers, Andrew, Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century, Oxford University Press and the National Gallery of Australia, 1994, 176p. Forward by Lin Onus and chapter by Carol Cooper.

-----, Aboriginal Artists of the Nineteenth Century [exhibition catalogue essay], National Gallery of Australia, 1994.

-----, Mickey of Ulladulla (1820–1891), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Australian National University, Canberra, 2005.

Smith, Keith Vincent, Mickey of Ulladulla (b. c.1825), Design and Art Australia Online, 2011.

State Library of New South Wales, The world of Mickey of Ulladulla [curriculum resource], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, n.d.

-----, Mickey of Ulladulla - Student Activity [curriculum resource], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, n.d.

-----, The world of Mickey of Ulladulla [curriculum resource], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, n.d.

-----, Making sense of a changing world [curriculum resource], State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, n.d.

Tommy Macrae and Mickey of Ulladulla [video], Hidden Treasures, National Gallery of Australia, 2006, duration: 5.30 minutes.

Tommy Macrae and Mickey of Ulladulla, National Film and Sound Archive, Canberra . [curriculum resource]

-----------------------

8. Acknowledgements

In the compilation of this work I would like to acknowledge the pioneering research of Andrew Sayers. Also, thank you to Steve Tranter of the Clarence River Historical Society, and to Lisa Ogle and Georgie Lowe for motivation and support in compiling this resource.

------------------------

Shoalhaven & South Coast: Aborigines / Indigenous / First Nations archive | Amootoo | Arawarra | Aunty Julie Freeman art | Berry's Frankenstein & Arawarra | Blanket lists | Broger | Broughton | Bundle | Byamunga's (Devil's) Hands | Cornelius O'Brien & Kangaroo Valley | Cullunghutti - Sacred Mountain | Death ... Arawarra, Berry & Shelley | God | Gooloo Creek, Conjola | Indigenous words | Kangaroo Valley | Jerribaley Cemetery | Mary Reiby & Berry | Mickey of Ulladulla | Minamurra River massacre 1818 | Moruya monster | Mount Gigenbullen | Neddy Noora breastplate | Timelong | Towwaa 1810 | Ulladulla Mission | Yams |

Last updated: 8 November 2024

Michael Organ, Australia

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment