Captain Cook's disobeyance of orders 1770

-------------------

Contents

- The ultimate genocidal action

- The Admiralty Orders

- The Royal Society Advice

- The repudiation of duty 1770

- Discovering a 'discovered' land

- Illegal possession of possessed Country & terra nullius lie

- Shoot first @ Botany Bay

- The invasion of 1788

- Possession as myth

- References / Bibliography

-------------------

1. The ultimate genocidal action

Lieutenant James Cook, in charge of HMB Endeavour, disobeyed direct, written orders when he claimed the east coast of Australia in the name of His Majesty King George III on 22 August 1770, denying the existence and rights of the Indigenous population.

Royal Navy Lt. Commander James Cook made a significant and fatal decision during his visit to the east coast of Australia in 1770 in charge of HMB Endeavour – he decided to disobey the the two sets of written orders given him by the Lords of the Admiralty and the head of the Royal Society (Douglas 1768, Stephens 1768). Both documents were in regard to dealing with local Indigenous populations and the making of territorial claims on behalf of the British Crown. They clearly stated that he was to deal with the local people as equals, and was not to make any territorial claims over them. Cook chose to ignore the orders and advice. This disregard by Cook was to have catastrophic, genocidal impacts upon the Aboriginal population of Australia, from 1770 through to the present day. His action lies at the heart of the dispossession of Australia's Indigenous / First Nations peoples from Country, and genocide in many parts thereof.

-------------------

2. The Admiralty orders to Lt. Cook

On 30 July 1768 the Lords of the Admiralty - the chief military officers of Great Britain - prepared additional orders for Lt. Cook that he was only to open upon completion of the scientific section of the Endeavour expedition. This took place once the transit of Venus was observed at Tahiti. The orders were then opened and, as a result, the Endeavour sailed south westerly towards New Zealand and Australia. Due to their sensitive political nature, the orders were marked Secret. They read as follows:

Secret

By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of Great Britain &ca.

Additional Instructions for Lt James Cook, Appointed to Command His Majesty’s Bark the Endeavour

Whereas the making Discoverys of Countries hitherto unknown, and the Attaining a Knowledge of distant Parts which though formerly discover’d have yet been but imperfectly explored, will redound greatly to the Honour of this Nation as a Maritime Power, as well as to the Dignity of the Crown of Great Britain, and may tend greatly to the advancement of the Trade and Navigation thereof; and Whereas there is reason to imagine that a Continent or Land of great extent, may be found to the Southward of the Tract lately made by Captn Wallis in His Majesty’s Ship the Dolphin (of which you will herewith receive a Copy) or of the Tract of any former Navigators in Pursuit of the like kind, You are therefore in Pursuance of His Majesty’s Pleasure hereby requir’d and directed to put to Sea with the Bark you Command so soon as the Observation of the Transit of the Planet Venus shall be finished and observe the following Instructions:

You are to proceed to the Southward in order to make discovery of the Continent abovementioned until’ you arrive in the Latitude of 40°, unless you sooner fall in with it. But not having discover’d it or any Evident sign of it in that Run you are to proceed in search of it to the Westward between the Latitude beforementioned and the Latitude of 35° until you discover it, or fall in with the Eastern side of the Land discover’d by Tasman and now called New Zeland.

If you discover the Continent abovementioned either in your Run to the Southward or to the Westward as above directed, You are to employ yourself diligently in exploring as great an Extent of the Coast as you can, carefully observing the true situation thereof both in Latitude and Longitude, the Variation of the Needle; bearings of Head Lands Height direction and Course of the Tides and Currents, Depths and Soundings of the Sea, Shoals, Rocks &ca and also surveying and making Charts, and taking Views of Such Bays, Harbours and Parts of the Coasts as may be useful to Navigation.

You are also carefully to observe the Nature of the Soil, and the Products thereof; the Beasts and Fowls that inhabit or frequent it, the Fishes that are to be found in the Rivers or upon the Coast and in what Plenty and in Case you find any Mines, Minerals, or valuable Stones you are to bring home Specimens of each, as also such Specimens of the Seeds of the Trees, Fruits and Grains as you may be able to collect, and Transmit them to our Secretary that We may cause proper Examination and Experiments to be made of them.

You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to besurprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents.

You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.

But if you shall fail of discovering the Continent beforemention’d, you will with upon falling in with New Zeland carefully observe the Latitude and Longitude in which that Land is situated and explore as much of the Coast as the Condition of the Bark, the health of her Crew, and the State of your Provisions will admit of having always great Attention to reserve as much of the latter as will enable you to reach some known Port where you may procure a Sufficiency to carry You to England either round the Cape of Good Hope, or Cape Horn as from Circumstances you may judge the Most Eligible way of returning home.

You will also observe with accuracy the Situation of such Islands as you may discover in the Course of your Voyage that have not hitherto been discover’d by any Europeans and take Possession for His Majesty and make Surveys and Draughts of such of them as may appear to be of Consequence, without Suffering yourself however to be thereby diverted from the Object which you are always to have in View, the Discovery of the Southern Continent so often Mentioned. But for as much as in an undertaking of this nature several Emergencies may Arise not to be foreseen, and therefore not to be particularly to be provided for by Instruction beforehand, you are in all such Cases to proceed, as, upon advice with your Officers you shall judge most advantageous to the Service on which you are employed.

You are to send by all proper Conveyance to the Secretary of the Royal Society Copys of the Observations you shall have made of the Transit of Venus; and you are at the same time to send to our Secretary for our information accounts of your Proceedings, and Copys of the Surveys and discoverings you shall have made and upon your Arrival in England you are immediately to repair to this Office in order to lay before us a full account of your Proceedings in the whole Course of your Voyage; taking care before you leave the Vessel to demand from the Officers and Petty Officers the Log Books and Journals they may have Kept, and to seal them up for our inspection and enjoyning them, and the whole Crew, not to divulge where they have been until’ they shall have Permission so to do.

Given under our hands the 30 of July 1768

Ed Hawke, Piercy Brett, C Spencer

By Command of their Lordships

[SIGNED] Php Stephens

The orders, or instructions, were very clear in regard to how Cook was to deal with any Indigenous population met with, and the lands of which they were in possession of. It is also very clear that Cook disobeyed each and every one of those orders.

It is interesting to note that the instructions were written as though there was not a lot of information available on the Southern Continent so often Mentioned, despite the readily available maps which dated back to the early 1600s (refer discussion below). Whether the Lords of the Admiralty were referring to the continent subsequently called Australia, or another located further south, is not clear. They were obviously aware of New Zealand and the discoveries of Abel Tasman, including that part of Australia subsequently known as Tasmania on 24 November 1642. They would also have been aware, as was Cook, that the continent of Australia had been precisely mapped, and only the detail of its eastern coast had not publically been revealed due to historic political and territorial agreements between the national states of Spain and Portugal.

-------------------

3. The Royal Society Advice

The first Endeavour expedition was important and public enough for the Royal Society to write specifically to Cook and the senior members of the venture cautioning them against abuses of Indigenous peoples. Unfortunately the subsequent actions of Cook and his crew were diametrically opposed to the advice received from James Douglas, 14th Earl of Morton of the Royal Society in regard to the treatment of Indigenous peoples and respect for their rights (Douglas 1768). Though couched in terms of the perceived racial superiority of the British, the advice was unambiguous and humane. It was given in light of knowledge of recent depredations and abuses by British sailors in the Pacific, as the following extract clearly reveals:

2. Hints offered to the consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr Bankes, Doctor Solander, and the other Gentlemen who go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour.

To exercise the utmost patience and forbearance with respect to the Natives of the several Lands where the Ship may touch.

To have it still in view that sheding the blood of those people is a crime of the highest nature:— They are human creatures, the work of the same omnipotent Author, equally under his care with the most polished European; perhaps being less offensive, more entitled to his favor.

They are the natural, and in the strictest sense of the word, the legal possessors of the several Regions they inhabit.

No European Nation has a right to occupy any part of their country, or settle among them without their voluntary consent.

Conquest over such people can give no just title; because they could never be the Agressors.

They may naturally and justly attempt to repell intruders, whom they may apprehend are come to disturb them in the quiet possession of their country, whether that apprehension be well or ill founded.

Therefore should they in a hostile manner oppose a landing, and kill some men in the attempt, even this would hardly justify firing among them, 'till every other gentle method had been tried.

There are many ways to convince them of the Superiority of Europeans, without slaying any of those poor people.—for Example.—

By shooting some of the Birds or other Animals that are near them;— Shewing them that a Bird upon wing may be brought down by a Shot.— Such an appearance would strike them with amazement and awe.— Lastly to drive a bullet thro' one of their hutts, or knock down some conspicuous object with great Shot, if any such are near the Shore.

Amicable signs may be made which they could not possibly mistake.— Such as holding up a jug, turning it bottom upwards, to shew them it was empty, then applying it to the lips in the attitude of drinking.—The most stupid from such a token, must immediately comprehend that drink was wanted.

Opening the mouth wide, putting the fingers towards it, and then making the motion of chewing, would sufficiently demonstrate a want of food.

They should not at first be alarmed with the report of Guns, Drums, or even a trumpet.—But if there are other Instruments of Music on board they should be first entertained near the Shore with a soft Air.

If a Landing can be effected, whether with or without resistance, it might not be amiss to lay some few trinkets, particularly looking Glasses upon the Shore: Then retire in the Boats to a small distance, from whence the behaviour of the natives might be distinctly observed, before a second landing were attempted.

Other and more important considerations of this kind will occurr to the Gentlemen themselves, during the course of the Expedition.

Upon the whole, there can be no doubt that the most savage and brutal Nations are more easily gained by mild, than by rough treatment.

As resistance may in some emergencies become absolutely necessary for self defence.—Training the men to fire at a mark, as was practised during one part of Lord Anson's voyage, and giving premiums or conferring some mark of distinction upon those who are most adroit, might have good effect, if it raised only emulation, without animosity. The last by all means should be carefully avoided.

If during an inevitable skirmish some of the Natives should be slain; those who survive should be made sensible that it was done only from a motive of self defence; for which reason no rancour should appear to continue on account of their having attacked or perhaps killed some of the Crew when on Shore, or having opposed their Landing: But the Natives when brought under should be treated with distinguished humanity, and made sensible that the Crew still considers them as Lords of the Country. Such behaviour would soon conciliate them to a familiarity with the Crew, and raise friendly sentiments towards supplying their wants.

But caution should be observed, as to the partaking of any food or liquors they may tender; unless the natives themselves do first taste of the same.

From the reports handed about concerning some of the late Expeditions, it should seem that upon one or two occasions, some of the Natives had been wantonly killed without any just provocation:— Particularly, a single man, who was killed in attempting to Swim towards one of the Boats.—If this account be true there was not the colour of a pretence for such a brutal Massacre:— A naked man in the water could never be dangerous to a Boats Crew.

Cook took these instructions to heart. He did indeed treat the people he encountered with a level of respect and fairness that was unusual at the time. He also passed these instructions on to his crew, ordering them to ‘endeavour by every fair means to cultivate a friendship with the Natives and to treat them with all imaginable humanity’.

Cook's actions reflect the opposite. His failings, and those of his crew, are therefore all the more unforgivable, as the precise account below reveals. It is, furthermore, extremely sad that Cook and his crew should treat the Indigenous peoples of Australia and New Zealand with so little respect, and in direct contravention of the Royal Society advice.

|

| John Hamilton Mortimer, Cook Claims Australia, oil painting, National Museum of Australia. From left: Karl Solander, Joseph Banks, James Cook, Dr John Hawkesworth and Lord Sandwich. |

------------------------

4. The repudiation of duty - 1770

It is clear Cook read the Admiralty orders and Royal Society advice, as they dealt with the action he was to take following completion of the scientific aspect of the expedition, which involved observation of the transit of Venus at Tahiti on 3 June 1769. We know this because, after that date, he steered HMB Endeavour south and west in search of the supposedly unknown Terra Incognita, as per the orders. This was despite the fact that it had already been 'discovered' and mapped on numerous occasions. In fact, Cook, as an experienced cartographer, had on board the Endeavour various maps which clearly outlined the extent of the continent as then known. Within some of those maps the east coast was not presented due to political constraints, which are referred to below. Abel Tasman's map of 1644 was one of those which revealed the comprehensive mapping of the continent which had taken place more than 125 years previous to Cook's firth voyage to the Pacific.

|

| Abel Tasman's map of 1644 - showing parts of Australia, Tasmania, Papua New Guinea and New Zealand. See more pre-1770 maps below. |

We can also assume that Cook read the advice offered by the Royal Society, given the import of that learned institution and it's role in the setting up of the scientific portion of the Endeavour expedition and the role of botanist Joseph Banks on board as chief scientist. However, to all intents and purposes, Cook chose to ignore specific elements of the orders and advice, instead taking action which was beneficial to the Crown and his own reputation, at the expense of the Indigenous population. Why did he do this? Why would he repudiate all the information and instructions directed to him?

James Cook was a military man. He was also a sailor and skilled cartography, having previously worked in the American colonies. He was not a politician, scientist or humanitarian. He is famous for many of the things he was, whilst the things he was not are not generally referred to, or highlighted. His fateful action in [supposedly] taking possession of the east coast of Australia at Possession Island on 22 August 1770, on behalf of King George III, in direct contravention of his orders, was in hindsight his most significant failing. Despite the fact that it provided a bonus for the ever-expanding British Empire and facilitated the acquisition of a new territory - a vast continent - to be used and exploited by the Crown, it had a catastrophic impact upon the Indigenous people, for it was here in 1788 that a penal colony - a brutal prison - was subsequently established under the control of the British military establishment. Such a prize for Cook - the possession, and claim to ultimate 'discovery' (yet again), of the continent hitherto referred to separately, or in combination, as New Holland or Terra Australis - raised his standing amongst the Admiralty, his peers, and the general public. It lead to his promotion to captain and further commands. However, his original act of not following the specific Admiralty orders, or the specific and legal humanitarian advice of the Royal Society, must forever cast a dark shadow over his reputation as an explorer, discoverer, cartographer and ship's captain. It reveals him to have neglected, rejected and ignored much of import in his professional and personal pursuit of 'maritime power' - a term specifically referred to at the head of the aforementioned orders. It also reveals his role in a society in which what was said officially - either in public or private - and what was done by officers such as Cook, were often two very different matters. The path which lead Cook to ignore written orders from the Admiralty and written advice from the Royal Society extended back a couple of centuries, to the very early days of the British Empire as it became known. The initial step was in claiming land, in 'discovering' land, in invading land and in 'civilising' populations which had previously been claimed, discovered, inhabited and civilized by, for example, Indigenous people. It was clearly a quest for power on the part of the British, and the rights of the latter groups were to be ignored, and beaten down if challenged. Cook was no saint; he was a soldier / sailor doing a job on behalf of a conquering power. The Endeavour expedition was just another part of that job.

-------------------

5. Discovering a 'discovered' land

Lieutenant Cook's orders contained sections of both clarity and ambiguity, with two elements at the core of the aforementioned charge of disobedience made by the present author and, as far as he is aware, by no other. The first of these required him, as commander of HMB Endeavour, to precisely locate ('discover') and chart the hitherto undiscovered Southern Continent. It's supposed existence was based on scientific conjecture and maps from the 1500s, if not earlier. This continental mass appeared to the British, and other contemporary maritime powers, to be located in that vast area of the Pacific Ocean east of New Zealand and west of South America, above latitude 40 degrees south. Cook did not find it in this location during a cursory look on his first voyage, though he proved its non-existence on his second voyage of 1772-1775 when he traveled throughout that area and further south towards the polar region as far as latitude 71 degrees, within 80 miles of the Antarctic ice shelf.

At the end of the day, Cook did not discover that so-called Great South Land. Instead, he instead looked west of New Zealand, to the land known as Terra Australis which had already been substantially mapped. As are result, he was able to proclaim a successful voyage in that he encountered and mapped in some detail the two islands of New Zealand and the east coast of Australia - both of which had previously been 'discovered', in part, by Europeans. Cook charted them with some precision, and also came to the conclusion that a landmass existed below the Antarctic Circle - not Terra Australis, but the continent of Antarctica. The latter would not be revealed - i.e. 'discovered' - until the 1820s, by Russian and European explorers and commercial sealers.

Cook's secondary orders of 1768 were very specific in what he should do if he were to come across such a continent in the indicated location. The orders did not, however, specifically refer to what he should do to any land he came across west of New Zealand, discovered or undiscovered, such as the then relatively well-known and previously 'discovered' continental mass located directly south of the East Indies (Indonesia), and referred to on various maps as New Holland or, rather confusingly, as Terra Australis. Nevertheless, it seems that he applied some selected elements of the orders in his actions upon charting the east coast of Australia. So what Cook and the British did, in a sleigh of hand, was to turn the known and largely mapped Terra Australis into the mysterious Great South Land and promote it to the public as such. This lie - that Cook had discovered the Great South Land and not merely mapped part of a continent that had already been mapped - was to have tragic repercussions for its Indigenous inhabitants.

The Australian continent, including Tasmania, had been inhabited for more than 130,000 years by the local Indigenous population, herein after referred to as the Australian Aborigines, though also, more recently, as First Nations Peoples. Their origins remain unclear, with science suggesting they were part of an Out-of-Africa migration, though the Aborigines themselves have a tradition of inhabiting the continent for a timeless period. The recently discovery of affiliation with the Denisovan humanoid species would tend to support a much early development, prior to the more recent 65K year old Out-of-Africa event so commonly referred to. The peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific had likely known of the Australian continent's existence for millennia, with humanoids in Indonesia up to 1.1 million years ago.

The continent had been precisely identified, or 'discovered', by Europeans since the early 1500s, following the arrival of the Portuguese in the East Indies (Indonesia) during 1512. Its northern and western sections were first mapped by them. Unfortunately, the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas had divided the newly discovered lands outside of Europe between Spain and Portugal, the two top maritime powers at the day. Those lands west of the 135 degree meridian - which passed through the approximate centre of continental Australia - 'belonged' to Portugal and those to the east, to Spain. Portugal was defeated by the Netherlands (Dutch) in 1661 and they thereafter took control of their foreign lands and colonies.

|

| Hollandia Nova / Terre Australie [printed map], Jean Bleau, 1659 [Dutch]. |

|

| Bellin and Schley, Carte Reduite des Terres Australes [printed map], 1758 [French]. |

The 16th century Dieppe maps of the east coast of Australia reflect the secretive cartographic work of the Portuguese during the years immediately follow their arrival in Java. That is, the Portuguese secretly mapped the whole of the Australian continent, but did not make this public through publication. According to a recent article by two Australian academics, the Jean Rotz world map of 1542, which makes use of Portuguese cartography, shows a good 'first approximation' of the east coast of Australia and Tasmania (Lees and Laffan 2019).

|

| Java La Grande [copy of Dieppe Map], 1547. Shows the east coast of Australia and Tasmania. |

The northern, western and southern coasts of Australia were 'discovered' and mapped in detail by the Portuguese / Dutch during the 1600s. The land also became known as Neu Holland / Hollandia Nova / Terra Australie and part of the treaty claim. It is precisely outlined in numerous Dutch and French maps published, for example, in 1659 and 1758, thereby revealing evidence of the cartographic skills in place by the middle of the 17th century, and more than a century before Cook.

These, and other pre-Cook maps, do not generally include the Portuguese / Dutch elements dealing with the east coast, as these were largely in manuscript form, unpublished, often secret, unconventionally projected, and subject to the tenets of the 1494 treaty under which Spain claimed sovereignty. The treaty was largely ignored by the British and in abeyance by the time Cook sailed. A large English version of the Bleau map of 1659 was published in 1744 and noted the earlier European discovery of the southern continent known as Hollandia Nova[west] / Terra Australis [east].

|

| Hollandia Nova [west] / Terra Australis [east], 1659 [1744 edition]. |

Much of the continent was therefore already known, or 'discovered', by the time the Endeavour left England in 1768. Cook and the Admiralty knew this. He was therefore able, through circumstance, to add to a process already begun, and ultimately completed by Matthew Flinders with his circumnavigation and precise mapping of Australia between 1801-1803. Cook's cartographic task was relatively simple for one as experienced as he, with the shallow draught former collier Endeavour well suited to the necessary close-in survey work which would refine the Dutch and Portuguese mapping and reconnect the dots between Point Hicks in the south and Cape York in the north. In regard to this work, Cook and his crew performed brilliantly. They precisely defined the east coast of Australia, using the most up to date equipment, and prepared a relatively detailed map of the coastline.

-------------------

6. Illegal possession of possessed Country

Cook's second task upon 'discovering' the (non-existent) unknown southern continent east of New Zealand, was to open negotiations with the Indigenous population in order to secure a safe port for British naval and commercial interests. The relevant section from his Admiralty orders reads as follows:

You are likewise to observe the Genius, Temper, Disposition and Number of the Natives, if there be any, and endeavour by all proper means to cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them, making them presents of such Trifles as they may Value, inviting them to Traffick, and Shewing them every kind of Civility and Regard; taking Care however not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents. You are also with the Consent of the Natives to take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors. (Lords of the Admiralty Instructions to Lt. Cook, 30 July 1768)

Cook failed miserably in the task of applying these orders to the already 'discovered' Southern Continent Neu Holland / Terra Australis which he encountered west of New Zealand. He was no diplomat, and never sought, or received 'the Consent of the Natives' before making claim as first discoverer and possessor of the east coast. In addition, for an unknown reason, he disregarded the very existence of the local Aboriginal population, despite observing them close at hand at Botany Bay and Cooktown, and also from off shore along the entire length of the coast. He was very much aware that his landing at Botany Bay on 29 April had been opposed by two local men. He also ignored their vehement claims to sovereignty over the land, when he took possession of a terra nullius [uninhabited land] on behalf of the British Crown at Possession Island off the coast of Queensland on 22 August 1770. At that time his rewritten journal contained the following record:

Notwithstanding I had in the Name of His Majesty taken possession of several places along this Coast, I now once more hoisted English Coulers and in the Name of His Majesty King George the Third took possession of the whole Eastern Coast ... by the name New South Wales, together with all the Bays, Harbours, Rivers and Islands situate upon the said coast, after which we fired three Volleys of small Arms which were Answerd by the like number from the Ship.

In taking this and prior similar action, Cook was in direct defiance of his Admiralty orders, as he at no time took possession of any land "with the Consent of the Natives." It was not until the Mabo ruling of the High Court of Australia in 1992 that this 'legal fiction' was deemed invalid, and recognition of Native Title at the time of Cook's encounter was accepted as legal truth in the eyes of British / Australian law, rather than traditional Aboriginal lore and right.

From Cook's acts of disobedience in this singe matter, everything thereafter came to the Australian Aboriginal people: invasion, death, disease, dispossession, unofficial slavery, cultural genocide, imprisonment and death in custody, stolen generations and ongoing racial discrimination. Cook’s actions revealed him for what he was, and what he was not. In regard to the Australian Aboriginal people he definitely was not able to 'cultivate a Friendship and Alliance with them'; neither was he an enlightened humanitarian in tune with the thoughts and beliefs of those who had written the Admiralty orders or Royal Society advice, otherwise he would have carried them out to the letter.

It has been argued in recent times that if the British had not taken possession of the continent, then some other Western nation such as France or Germany or Holland would have done so. This may be true, but it does not excuse Cook's actions in doing what he did. So, why did he do this? Why was he unable to deal with Indigenous populations of the Pacific, New Zealand and Australia in a respectful and compassionate manner? Why did the 'military power' imperative appear to override all others?

Evidence of this failing in respect of Indigenous rights can be seen in his premature death at the hands of the Hawaiians in 1779 whilst attempting to kidnap their King Kalani ʻōpuʻu. Cook was a military man, through and through; a Royal Navy officer and ship's commander experienced in war, and especially skilled in cartography. For the latter, and as an explorer / discoverer he has been eulogised. However, beyond this, he was as flawed and human as anyone, and a product of his time and upbringing. He was surrounded by an environment of racial superiority and class prejudice. The journal of Joseph Banks, for example, is full of racist remarks towards the Aborigines, and it may be that we look to him to explain some of the actions of the ship's captain. To excuse such remarks as ‘of their time' and therefore excusable, is not acceptable, and never was. In 1770 many British subjects believed Western civilisation and themselves as individuals were racially superior to native peoples such as the New Zealand Maori and Australian Aborigines. They had little respect for Indigenous culture, saw the people as mere ethnographic specimens, labelled them as 'primitive', 'savage' and 'uncivilised', and denied them any rights in regard to property, law and custom. This was clearly racism at its worst, backed by a class-based arrogance which was especially strong with the British, and reinforced therein by a monarchical system reigning over an immature democracy where all individuals were decidedly not equal. We know this from the historical records - the manuscript journals and diaries, the published texts, and the pictorial record of Cook's voyages. Yet the humanity present in the Royal Society advice would suggest otherwise, and the words therein are just as relevant today as they were back in 1768 when atrocities were being carried out by the British.

---------------------

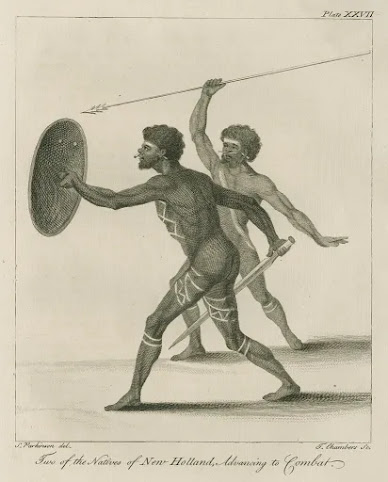

7. Shoot first

The harsh reality of the treatment of Indigenous peoples is exemplified in the actions of Cook and his crew during 1769-70. It is why, for example, when the Endeavour dropped anchor in Botany Bay on 29 April 1770 and a boat was lowered to take a party of sailors and marines on shore, Cook took the lead at the head of the boat, with rifle in hand. What happened next can only remind us of the Black Lives Matter issue of 2020 and the ever-present application of unwarranted force by the military and police in dealing with confrontations with individuals who are 'other'. An aggressive, militaristic stance was reflected in Cook's orders, with the warning from the Lords of the Admiralty upon encountering native populations 'not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them, but to be always upon your guard against any Accidents'. The wise, compassionate and humane words of the Royal Society dissipated, and a military posture was adopted.

Cook and his crew had engaged in fierce encounters with the Maori prior to arrival in Australia. They killed nine people shortly after their arrival there, in what appears to have been an extreme British response to the traditional Maori haka welcome. They were to do the same a few weeks later on first encountering the Australian Aboriginal people. Such behaviour by the British would be consistently applied throughout the following century, with a barbaric degree of normalcy.

On our approaching the shore, two men, with different kinds of weapons, came out and made toward us. Their countenance bespoke displeasure; they threatened us, and discovered hostile intentions, often crying to us, Warra warra wai [Go away!]. (Sidney Parkinson, Botany Bay, 29 April 1770)

|

| The Aboriginal perspective - opposition to landing, trinkets on offer. Cook stands ready to fire. |

|

| Close to the truth - guns fired as Cook lands. |

.jpg) |

| The mythological view - Cook as icon, landing on the sandy beach and taking possession, with guns aimed to be fired. |

The Australian Aborigines were defending their Country, just as Westerners would, in turn, defend their property. Cook was forcefully asked not to come upon their land. However, he was an aggressive invader, breaking Aboriginal law and custom in not acceding to this request / demand. By coming onto their land when clearly told not too, Cook was actually undertaking an act of invasion. This initial act of invasion by Cook has never been accepted as such by those in authority outside of the Aboriginal community. However, the facts of history are clear, and it cannot be viewed in any other way, then or now. Cook invaded Australia on 29 April 1770.

Captain Cook's ship laid on the shoreline of the northern coast of New Holland (now Cooktown Queensland) for hull repairs. Engraving by Rennoldson.

We now understand and accept the implications of Cook's actions in laying the foundation for the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, the transformation of Australia into a penal colony, and all that came with it; even the declaration by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1816 of a war of terror against the local Aboriginal people, and the massacre of men, women and children at Appin as an "unfortunate" outcome of that, as an example of the so-called collateral damage which is a part of every war.

Cook showed immense disrespect for the Australian Aborigines. He did not make that effort to sit down with them and come to an agreement, as per his orders. He did not seek to get their permission to use Botany Bay, or some other part of Australia, as a port for naval and commercial use by the British. He simply planted a flag and took possession. Additionally, his secret orders said that if the land was inhabited he was to negotiate and not claim it for the British Crown. He knew it was inhabited, and that the local people did not welcome the British there. How then, could he possibly claim the land was terra nullius? How could he state that the land was uninhabited, and then take possession of it after spending all that time in close contact with the people of Cooktown and Botany Bay? What caused Cook to decide to claim the east coast of Australia on behalf of the King when his orders clearly stated he was not to do this? Ego? Bravado? A feeling of cultural and military superiority? His orders were to talk to the local people, negotiate with them and come to an agreement with them. This he did not do. Not only did he not do that, but he acted with extreme prejudice. He was aggressive in New Zealand where people were shot. He was aggressive in Australia where people were shot. This lack of compassion and respect is a core issue amongst Aboriginal people and students of history who may initially have viewed Cook as a great explorer, discoveries of continents and humanitarian.

---------------------

The English invasion of Australia in January 1788 under the military command of Governor Arthur Philip, following on the actions of Royal Navy Lieutenant Commander James Cook aboard HMB Endeavour in 1770, have had a devastating and tragic effect on the Indigenous / Aboriginal population. Emotive terms such as 'invasion' and 'cultural genocide' are rightly applied. A recent tweet by appropriately named Australian health official Annaliese van Dieman brought this point home with great contemporary relevance:

Sudden arrival of an invader from another land, decimating populations, creating terror. Forces the [Indigenous] population to make enormous sacrifices & completely change how they live in order to survive. COVID19 or Cook 1770? Annaliese van Dieman, Deputy Chief Health Officer, Victoria, 29 April 2020.

The state of the country as it presently exists is plain to see - Aboriginal financial and societal disadvantage, chronic health issues, racial discrimination, loss of association with Country, loss of culture and tradition, extraordinary levels of imprisonment, high mortality rates, and a denial of responsibility for any of this by the invaders. As this is written, the truth about what happened back in 1770 and 1788 remains shrouded in mystery, meaningfully hidden and, where it is revealed, quickly rejected by non-Aboriginal society and its leaders and commentators. Likewise part of this denial is the decades of war, massacres and brutality fostered upon the Aboriginal population, in a manner not unlike the treatment of Black people in the United States and other ethnic groups elsewhere, such as the Tibetans and Mongolians in present-day China. The fact is, that in 1770 and 1788, in Botany Bay and Sydney Cove, and later elsewhere, the aggressive and angry cry was heard all around Australia from Aboriginal people upon the approach of Europeans: Warra Warra Wai! - [Go away! / Go far away!] (Smith 2019).

---------------------

Postscript: Australian historian Graeme Taylor has argued that, following his death in 1779, Cook's original journal was doctored and the whole Possession Island event was concocted by British authorities to facilitate a claim over Terra Australis. He noted that the published journal of Joseph Banks made no mention of it. If this is true, the above scenario would be subject to a rewrite and criticism of Cook over his unwarranted acts of possession would be diminished, though his failure to open communication with the local Indigenous population would remain.

---------------------

10. References / Bibliography

The aim of this blog is to bring to light, once again, or for the first time, facts about the history of Australia which can, and should, influence the way forward, with an emphasis on the defining events of 1770 and 1788. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and stalled 2020 250th anniversary celebration / commemoration of Cook's landing at Botany Bay on 29 April 1770, one positive aspect has been a discussion of these events from an Aboriginal perspective - something which has frankly not been done before, and not in such a public way. The following listing of articles and videos are some examples of this, along with a wealth of new analyses from various, and traditionally different, perspectives regarding the true impact of Cook on Australian history and society.

* This Place: View from the Shore, ABC Television, March - April 2020. A series of video short films focusing on the history and culture of Indigenous communities along the east coast of Australia:

- Mount Gulaga and Garung-gubba, 6 minutes.

- This Is Our Country - Gamay (Botany Bay), 6 minutes.

- Three Brothers Mountain, Birpai nation, 3.50 minutes.

- Lake Burmeer: The Women's Lake, North Stradbroke Island, 6 minutes.

- How Dimpuna Became Mooloomba (Point Lookout, North Stradbroke Island), 6 minutes.

- Language Remains in the Landscape, Gooreng Gooreng people, 6 minutes.

- Cultural Knowledge is Empowering, Bunda Bunda clan, 6 minutes.

- Mungurru the Rock Python and Waalumbal Birri, Endeavour River, 6 minutes.

- Gudang Yadhaykenu on Possession Island, 6 minutes.

- Ankamuthi on Possession Island, 6 minutes.

- Kuarareg / Gudang Yadhaykenu on Possession Island, 6 minutes.

* Alexis Moran and Jai McAllister, Patyegarang was Australia's first teacher of Aboriginal language, colonisation-era notebooks show - ABC News, 11 March 2020.

* Vanessa Milton, The first sighting of James Cook's Endeavour, as remembered by the Yuin people of south-eastern Australia - ABC News, 18 April 2020.

* Ben Collins, What Australians often get wrong about our most (in)famous explorer, Captain Cook - ABC News, 20 April 2020.

* Mary Nugent and Gaye Sculthorpe, Tall ship tales: oral accounts illuminate past encounters and objects, but we need to get our story straight, The Conversation, 25 April 2020.

* Stephen Gapps, Make no mistake: Cook's voyages were part of a military mission to conquer and expend, The Conversation, 28 April 2020.

* Isabella Higgins and Sarah Collard, Captain James Cook's landing and the Indigenous first words contested by Aboriginal leaders - ABC News, 29 April 2020.

* Justin Bergman, Sunanda Creagh, Wes Mountain, Explorer, navigator, coloniser: revisit Captain Cook's legacy with the click of a mouse, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Maria Nugent, A failure to say hello: how Captain Cook blundered his first impression with Indigenous people, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Phoebe Roth, Sophia Morris, Sunanda Creagh, 250 years since Captain Cook landed in Australia, it's time to acknowledge the violence of the first encounters, Trust Me, I'm An Expert [podcast], The Conversation, 29 April 2020. Duration: 27.31 minutes.

* Alison Page, 'They are all dead': for Indigenous people, Cook's voyage of 'discovery' was a ghostly visitation, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Shino Konishi, Captain Cook wanted to introduce British justice to Indigenous people. Instead, he became increasingly cruel and violent, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Kate Darian-Smith and Katrina Schlunke, Cooking the books: how re-enactments of the Endeavour's voyage perpetuate myths of Australia's 'discovery', The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Louise Zarmati, Captain Cook 'discovered' Australia, and other myths from old text books, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* John Gasgoine, From Captain Cook to the First Fleet: how Botany Bay was chosen over Africa as a new British penal colony, The Conversation, 29 April 2020.

* Sunanda Creagh and John Maynard, An honest reckoning with Captain Cook's legacy won't heal things overnight. But it's a start, Trust Me, I'm An Expert [podcast], The Conversation, 29 April 2020. Duration: 30.08 minutes.

* Keith Vincent Smith, Warra Warra Wai, Eora People [blog], 26 April 2019. Available URL: https://www.eorapeople.com.au/uncategorized/warra-warra-wai-2/.

* Brian G. Lees and Shawn Laffan, 'The Lande of Java' om the Jean Rotz Mappa Mundi, The Globe, 85, June 2019, 1-12.

Stephens, Phillip, Secret Instructions to Lt. Cook 30 July 1768, Lords of the Admiralty, London. Available URL [Transcript]: https://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/nsw1_doc_1768.pdf.

Taylor, Graeme, Stirring the Pot of the Dead Cook, Sovereign Union - First Nations Asserting Sovereignty [webpage], 2020. Available URL: http://nationalunitygovernment.org.

-----, 'Over Cooked' - Is Captain Cook the Source of British Sovereignty in Australia", Sovereign Union - First Nations Asserting Sovereignty [webpage], 2020. Available URL: http://nationalunitygovernment.org.

Morton, James Douglas, Hints offered to the consideration of Captain Cooke, Mr Bankes, Doctor Solander, and the other Gentlemen who go upon the Expedition on Board the Endeavour [manuscript], Royal Society, London, 10 August 1768.

Last updated: 10 April 2024

Michael Organ, Australia (Home)

Hi Michael

ReplyDeleteI just wanted to comment on your postscript referencing Graeme Taylor arguing that Cook's original journal may have been doctored and the whole Possession Island event concocted post hoc by British authorities. You say Taylor noted that the published journal of Joseph Banks made no mention of it. I have read this argument of Taylor's on the site "Sovereign Union - First Nations Asserting Sovereignty" in an article headed "Stirring the Pot of the Dead Cook" (at http://nationalunitygovernment.org/content/stirring-pot-dead-cook ). I have not been able to find a point of contact for this "historian", but if I could I would make the following remarks. Taylor states incorrectly that "Possession Island was the only other place, besides Botany Bay and Endeavour River, where Cook and crew left the ship and went ashore". In fact, Cook and/or one of his party, went ashore at least 10 times (for example Cook also went ashore at Round Hill, Quail Island, Lookout Point, Lizard Island, and Booby Island). So Taylor's research seems inadequate on that score. Taylor also mentions "cannons" being fired at Possession Island but none of the records make any mention of cannons: only referencing "small arms" fire and "3 cheers". Another inaccuracy. And Taylor then says only Cook's (allegedly doctored) journal mentions the events on Possession Island. Taylor is correct that Banks' journal doesn't mention this, and I agree that is passing strange. However, the journals of others in Cook's party (for example, those of Forwood and Hickes,) do mention this taking of possession on Possession Island, albeit not in exactly the same terms. And, most notably, the ship's log itself, which shows no sign of tampering, says: "At 6 possession was taken of this country in his Majesty's name and under his coulours (sic); fired several volleys of small arms on the occasion, and cheer'd 3 times, which was answer'd from the ship". All of which makes me wonder how much research Taylor has done and how credible his surmising of the doctored journal is.

All that said, I am in total agreement that Cook disobeyed/ignored his Orders and the exhortations of the Royal Society regarding not seeking Consent of the Natives, taking taking possession as if the land was uninhabited, and his ready and unnecessary use of firearms. Regards, Fred Tromp.

Fred - thank you for your comments. Michael

Delete